The Black Box

Michael Connelly

My newly identified problem with crime fiction may start right here.

My newly identified problem with crime fiction may start right here.

Even as I wrote that sentence I realized it wasn’t fair. There’s another candidate in the running, but I’m nowhere near feeling certain about it. In this case, though, I know my exasperation led me to set the book aside for over three months.

You would think that with 50 or so pages to go I could have just toughed it out back in May.

I’ve written about Michael Connelly before (here and here) so you might think he’s a reliable, entertaining writer. Perhaps he is, but I still had trouble with this one.

On the face of it there’s no good reason for that. In this book , Connelly’s hero, Harry Bosch, is working a cold case. Like many crime authors, Connelly has a couple of primary characters he keeps coming back to. In the previous books I’ve written about that character has been Mickey Haller, who is a lawyer. In some convoluted way he’s also Harry Bosh’s half-brother.

LA’s Burning

The intersection of Florence and Normandie Avenues, April 29, 1992.

Bosch, though, has been around longer. I first encountered him in a book with two main characters, the other being an FBI profiler named Terry McCaleb. Harry was, is and probably always will be a homicide detective for the LAPD. Like many another detective who is on the job, Harry has little patience or use for bureaucracy, promotions or any of the folderol that accompanies it.

That, always, is the initial attraction to these characters. In their own way, they’re really just a more contemporary update of an earlier type: the gunslinger. And I suppose, before we had taciturn men on horseback holding to a code and saving whole towns, we had knights-errant. Give me a while and I’ll trace it back to Greek mythology and the argument that there are only seven or so stories, endlessly retold.

Back to Harry. How can I say this? Harry Bosch is…no, all of Connelly’s characters are….deadly serious. With the New York-based tecs, being a smart ass with a quick lip is virtually a requirement. If, like Matt Scudder, you aren’t yourself, then you have someone in your orbit who serves that purpose. (Or, like Lawrence Block, you just create a couple of series where the smart alecks rule.)

The National Guard arrives in LA in the midst of the riots.

It is not as though this is an East Coast-West Coast divide. For all their smoking and driving in silence, the heroes of Chandler, Hammett and Cain all had their amusing moments. Not Harry (or any of the others). If it wasn’t for Bosch’s somewhat improbable love of jazz I might have gotten off the bus a long time ago. But I picked up some things to listen to and so stuck around.

That brings me back to Harry who is now in an interesting position. He’s taken a retirement package and is working as a contract investigator–with seemingly most of the powers of a fully employed police officer–on cold cases. One has been irking him a long time. Anke Jespersen, a Danish photojournalist killed during the 1992 riots that followed the Rodney King verdict.

At the time, Bosch caught the call but the investigation was cut short, as so many were at the time, due to the rioting and ensuing chaos. The woman’s body, in fact, was discovered by a National Guard unit and so the facts delivered, as it were, with her corpse carried a certain weight.

There’s all types of sheriffs.

The late Clifton James as J.W. Pepper.

It’s now twenty years later and Bosch is back on the case, specifically asking to have it assigned to him. He’s also got a new lieutenant running his unit, a bureaucrat more interested in posting impressive stats than truth or justice. Of course there’s conflict. How can there not be? Just in case you don’t understand the source of that conflict, though, Bosch tells off the Lieutenant, in the process explaining the many ways the unwritten code of the true detective has no meaning to a careerist.

That might be Connelly’s first misstep. After ‘write about what you know,’ ‘show, don’t tell’ is probably the advice most widely proffered to would-be writers. So why tell me?

In any event, Bosch is on the case and with some new evidence and more time he makes progress. It soon becomes apparent that there might be more to Jespersen’s death than being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Bosch keeps pulling at threads, looking for the item(s) in the black box that will make the case come clear.

No, not Kansas.

Rural Cali on the I-5 corridor, where too many left coast mysteries have dwelt lately.

Which it eventually does. That resolution requires confrontation, deception and some significant time spent in rural counties straddling I-5. That’s actually more Grafton‘s country than Connelly’s and that didn’t help matters.

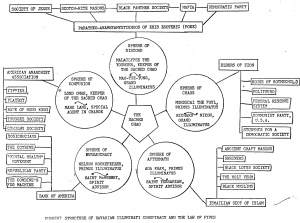

I’ve decided that writers intuitively understand what conspiracy theorists do not–the more people there are around the less likely a conspiracy is to work. It takes a village to effectively conspire and, as the Santa Theresa shamus discovered , a broadly gathered but finite group to pull it off. All those dictates are honored, but the form requires the hero to one up everyone and so Bosch does.

The result is an ending made for Hollywood. I won’t spoil it any more than saying you would have a hard time staging a comparable scene on the East Coast.

I tell people conspiracies can’t work and they look at me like I’m nuts. Here’s why I believe as I do.

None of this sounds like a reason to have an issue, does it? Yet I did. As with Doc Ford, this time Bosch comes closer than ever to donning the mantle of the vigilante. I understand the appeal, but I’ve never been comfortable with it.

I can handle being beholden to an unwritten professional code. That’s what separates the people you can trust from the ones who are dangerous. For that to work, though, it has to take place within a structure. And while I have an anarchic streak, there’s a difference between demonstrating that it is possible to do the right thing and doing your own thing.

That doing your own thing business goes a long way towards explaining the fix we’re in.

Advertisements Share this: