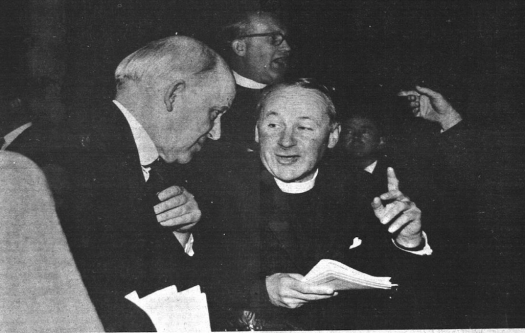

On the evening of the 18th October 1966 the powerful words of two distinguished and admired men within British Evangelicalism clashed in a way that created a significant gulf between two groupings of evangelicals, the consequences of which can still be seen, in part, in today’s evangelical landscape in the UK. Dr. Martyn Lloyd-Jones and Rev. John Stott were viewed by many as the unofficial leaders of evangelical non-conformity and evangelical Anglicanism respectively, and so both men had many ‘followers’ within their denominations and networks. In the following historical case study I will outline the public disagreement between these two men in 1966, where Lloyd-Jones made an impassioned call for ministers to secede from their denominations and come together in an evangelical union, after which John Stott closed the meeting with a strong rebuttal. After presenting the context and background of the reason for ‘the call’ I will seek to clarify misunderstandings from the evening and track later developments and repercussions of this debate. In the second section of the essay my attention will turn to the effect that this public disagreement has had over the last fifty years, focussing primarily on successes and failures within conservative evangelical non-conformity in the UK.

The Context of 1966

When seeking to understand the context of the meeting in which the disagreement took place, it is imperative to consider the broader landscape of the British church at this time. A noteworthy feature of this period was the dramatic rise and influence of the ecumenical movement. The British Council of Churches (BCC) was an ecumenical organisation founded in 1942 with the aim of uniting anyone who called themselves Christians. The BCC’s successor today, ‘Churches Together’, although influential in some areas, does not operate with anything like as much power and momentum of the BCC of this period. One evangelical minister remarked that a failure to be part of the ecumenical set-up (BCC) would give you little chance of being a hospital chaplain or even of maintaining planning permission to build a church building. The power of the ecumenical movement found its ‘high point’ in the 1964 ‘Faith and Order conference’ where the following statement reveals their ultimate goal: “United in our urgent desire for One Church Renewed for Mission, this Conference invites the member churches of the British Council of Churches, in appropriate groupings such as nations, to covenant together to work and pray for the inauguration of union by a date agreed amongst them… We dare to hope that this date should not be later than Easter Day, 1980. We believe that we should offer obedience to God in a commitment as decisive as this.” Rather than this desire being an abstract dream, the Anglicans and Methodists attempted to merge and the Congregational and Presbyterian Churches had gathered momentum into what would ultimately form the United Reformed Church.

Lloyd-Jones’ own altercations with ecumenism can be seen by his retreat from Billy Graham’s missions which he had originally supported. Although Lloyd-Jones was appreciative of Graham’s urgency in preaching the gospel he became concerned over Graham’s joining with Catholic and liberal leaders whom he invited to share the stage at missions. Upon challenging Graham on one example where a stage was shared with a well-known liberal minister, Graham replied: “You know, I have more fellowship with John Sutherland Bonnell than with many evangelical ministers.” I [Lloyd-Jones] replied, “Now it may be that Bonnell is a nicer chap than Lloyd-Jones—I’ll not argue that. But real fellowship is something else: I can genuinely fellowship only with someone who holds the same basic truths that I do.”

The significant rise of ecumenism and its appeal to some evangelicals sets the scene for Lloyd-Jones’ appeal of 1966.

The Evening itself

The full transcript of Lloyd-Jones’ address was published several years after the event under the title ‘Knowing the times’ in 1989. This publication helped to clear up some ambiguity about what was really said that evening. Lloyd-Jones had been invited by the Evangelical Alliance to present his views on the subject of Christian Unity to a gathering of evangelical minsters. The issue, as noted previously, was a considerably important one at the time and evangelical churches and their leaderships differed in their views of how they would respond to the challenge of ecumenism. “At its heart, Lloyd-Jones’s address was a call for visible unity among evangelicals to match their spiritual unity. He lamented that they were divided among themselves and ‘scattered about in the various major denominations . . . weak and ineffective.’” Lloyd-Jones’ appeal was both negative and positive, negative in that he clearly stated that those in mixed denominations found themselves in a ‘contradictory position.’ Yet positively he cast the vision for an opportunity for a coming together of like-minded evangelicals in what he famously coined “evangelical ecumenicity.” Furthermore, Lloyd-Jones appealed that coming together and standing firm together in the gospel could bring about revival and re-awakening brought to the church by the Holy Spirit. By all accounts Lloyd-Jones’ address was passionate, stirring and was even described by one observer as reminiscent of a ‘Lutheran act!’ Famously though, the evening did not end there and John Stott, the chairman for the event, rebutted Lloyd-Jones’ appeal in a move that some people viewed as an abuse of his position as chairman. Stott’s response focussed on the opinion that both history and scripture was against Lloyd-Jones. These two great leaders’ views were polarised with regards to a way forward and the evening signalled a change in the ways evangelical non-conformists and Anglicans related in the years to come.

Misunderstandings

In the aftermath of the event much was said and written, however some misunderstandings appear to be easily rectifiable. Howlett alludes to the fact that many after the event concluded that it was not Stott abusing his position as Chairman but that it was in fact Lloyd-Jones who abused his position to force his views on those gathered in a way in which was unexpected to the Evangelical Alliance Council. Although one could argue that Lloyd-Jones’ words came with power from the pulpit that could not have been anticipated, the EA Council were made aware in advance of Lloyd-Jones’ position, and Stott himself would have known this also. Another misunderstanding which holds more sway was the question of what exactly Lloyd-Jones was really calling those at the conference to? As Grills writes: “Many believe that the call was for evangelicals to leave the mixed denominations and join together in the creation of a new evangelical denomination. Others, appealing to Lloyd-Jones’ previous writings, have argued that he only urged evangelicals to come out of the denominations into a tighter unity between evangelical churches.” Stevens concludes on this point that perhaps Lloyd-Jones showed a lack of responsibility in failing to take on the mantle of being the leader of this union or showing a clearer way forward. Did his speech demonstrate “that it is always easier to tear down than to build?”

Further Developments

The events of 1966 were either seen as a great clarion call from Lloyd-Jones which gave many ministers the confidence to ‘come out’ from their denominations, or an inappropriate plea which in no way helped develop the evangelical unity which Lloyd-Jones desired. Grills writes: “By making an essentially ecclesiological issue the touchstone of orthodoxy he was, ironically, primarily responsible for creating a rift within British evangelicalism that has yet to be completely bridged.” On the other hand, those supportive of Lloyd-Jones’ views felt further justified when at the Keele Conference a year later in 1967, Stott, Packer and other evangelical Anglicans appeared to affirm their commitment to the ecumenical programme of the Anglican Church. This was viewed by many non-conformists as Anglicanism taking priority over Evangelicalism. Murray writes that there was a call at this conference for greater appreciation and openness to Anglo-Catholics and liberals within the Church of England and he remarks somewhat sardonically that “No chairman’s dissociation from a speaker’s remarks was heard then!” J.I Packer’s joint publication of “Growing into Union-Proposals for forming a united church in England” which included writings from a spectrum of views within Anglicanism was further proof to some that Lloyd-Jones’ appeal should have been acted upon with those in the Anglican church.

The last 50 years

Having sketched some brief examples of the immediate impact of 1966, let us now turn our attention to some key successes and failures in the last fifty years of British conservative evangelical non-conformity.

Successes

Standing firm despite opposition

It is clear to see that Lloyd-Jones’ appeal put steel in the backbone, to use a metaphor, of many non-conformist ministers and churches. Lloyd-Jones’ clear focus was on the need for the gospel and sound doctrine to be guarded, and his call led a generation to take up this challenge in standing firm for primary issues. The question raised by Lloyd-Jones is this: ‘what is true Christian unity?’ Raising this so publically has helpfully given courage for non-conformists to be bold in coming out of doctrinally mixed denominations and to choose to unite to those churches and groups which adhere to the faith.

Gospel Partnerships

There have been several encouraging initiatives in recent years to promote true gospel unity across denominational boundaries. One such example is the ‘Gospel Partnerships’ that have been established in the UK. Twelve such regional partnerships exist now with the aim of supporting each other in the work of proclaiming the gospel. The Doctrinal Basis is broad enough to include churches with Anglican and non-conformist ecclesiology but narrow enough to guard core doctrinal issues. Churches within these networks come together to share best practice, resources, training, and even to aid church planting. As well as being mutually edifying to leaders, these groups can demonstrate a visible example of churches working together to the watching world. FIEC Director John Stevens has said: “The emergence of the Gospel Partnerships over the past decade or so has been amongst the most significant developments in British evangelicalism, as conservative evangelicals from Anglicanism and the Free Church have joined together to serve the cause of Christ. They have done more to undo the damaging division inflicted in the late 1960s than any other initiative, and have fostered a true unity around the core doctrines of the gospel.”

FIEC Growth

Another area of success in light of 1966 is the rise of the FIEC’s influence in the UK Evangelical landscape. Westminster Chapel joined the FIEC the year after 1966 and Lloyd-Jones was convinced of its usefulness in bringing together like minded Independent churches. Over five hundred churches are affiliated to the FIEC today from several non-conformist groupings, and the number is growing. The benefits include conferences, mission strategy resourcing, training and pastoral care. John Stevens’ leadership has endeavoured to strike the balance between a desire for true gospel unity which bridges over denominational boundaries, yet at the same time holds to strong convictions and teaching over ecclesiology. This has led to the FIEC supporting Gospel Partnerships and missions between local evangelical churches. He is balanced in his analysis of Lloyd-Jones’ disagreements with Stott and Packer in a way which cannot be accused of hagiography, unlike some within his circles.

Parachurch organisations and events

One final success in promoting true gospel unity has been the success of UCCF (formerly IVF, pictured below). Lloyd-Jones and Stott were both heavily involved in this ministry and saw the importance in reaching university students. UCCF has had significant theological debates regarding the atonement and have not shied away from cutting ties with certain figures and groups, yet there remains an emphasis on true gospel unity. Students in such formative years have often come to understand the importance of working together in mission with Christians who share the core elements of the faith, even if there are areas where there is disagreement, and to wisely discern the difference between issues of primary and secondary importance. This has helped to heal some of the wounds of 1966. Conferences such as the Evangelical Ministry Assembly (EMA) has also helped in uniting conservative evangelicals. The conference established in 1986 has brought evangelicals together for training in expository ministry and for mutual fellowship. A talk given by Vaughan Roberts (an Anglican minister!) in 2014 at the conference on the ministry of Lloyd-Jones was a clear example on just how far Anglican/Non-conformist relations had come.

Failures

Suspicion of Evangelical Anglicans

One of the results of 1966’s rift between Anglicans and non-conformists was that there became a lack of generosity towards Anglican brothers and sisters. While Lloyd-Jones had great friendships with a number of Anglican clergy his disagreements with Stott and Packer were perhaps seen by some as an excuse to be suspicious towards anything or anyone Anglican. This attitude sadly lives on in many non-conformist churches today. Stevens notes that “MLJ was remarkable both for his doctrinal clarity, but also his gospel generosity. He was never as hard line as some of his subsequent followers became.” This generosity has sometimes been forgotten by those in later generations and led to a drawing back from partnerships like the Gospel Partnership Networks and even Bible colleges such as Oak Hill where Anglicans and Independents study alongside each other. It seems unfortunate that rather than wanting to support and pray for brothers and sisters battling in their denominations in the midst of mixed doctrinal teaching, churches and leaders would in reality distance themselves from gospel allies.

Isolationism

Although earlier I mentioned the FIEC’s work in bringing Independent churches together, in many places Independent churches still operate in isolation, not just with regards to Anglican Evangelical churches nearby but also fellow Independent churches. Some Reformed Baptist Churches have taken Lloyd-Jones’ logic much further than he did and have adhered to secondary separation, disassociating themselves from fellow evangelicals. This kind of mind-set has also led to idiosyncrasies on specific reformed issues that have led to needless arguments and separation – something surely Lloyd-Jones would have mourned?

Conclusion

In summary, we have seen that the events of 1966 have had significant impact on the UK conservative evangelical church. While both men’s legacy lives on, mostly through their writing ministries, much has been done since 1966 to unite Anglican and non-conformist evangelicals together again. This visible unity which is enjoyed today in many areas shows an encouraging trajectory in what can be done when genuine Christian unity is fostered.

Bibliography

Atherstone, Andrew, and David Ceri Jones. Engaging with Martyn Lloyd-Jones: The Life and Legacy Of “the Doctor.” Nottingham, England: Apollos, 2011.

Buchanan, Colin Ogilvie, ed. Growing into Union: Proposals for Forming a United Church in England. London: S.P.C.K, 1970.

Dudley-Smith, Timothy. John Stott: A Global Ministry. Leicester: InterVarsity, 2001.

Gospel Partnerships, “About Us” http://thegospelpartnerships.org.uk/about-us/the-working-basis-for-regional-gospel-partnerships

Grills, Andrew. “40 Years On: An Evangelical Divide Revisited” http://archive.churchsociety.org/churchman/documents/cman_120_3_grills.pdf

Guyer, Benjamin, ed. Pro Communione: Theological Essays on the Anglican Covenant. Eugene, Or: Pickwick Publications, 2012.

Henry, Carl F.H. “Martyn Lloyd-Jones: From Buckingham to Westminster,” Christianity Today (8 February 1980)

Howlett, Basil. 1966 and All That: An Evangelical Journey, 2016.

Lloyd-Jones, David Martyn. Knowing the Times: Addresses Delivered on Various Occasions 1942-1977. Edinburgh [U.K.]; Carlisle, PA: The Banner of Truth Trust, 2013.

Lloyd-Jones, David Martyn, and Iain H Murray. D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones: Letters 1919-1981. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1994.

Masters, Dr Peter. “Secondary Separation – When to Stand Apart from Biblical Error”

http://www.metropolitantabernacle.org/Christian-Article/Secondary-Separation-When-to-Stand-Apart/Sword-and-Trowel-Magazine

Murray, Iain Hamish. David Martyn Lloyd-Jones. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1983.

Roberts, Vaughan. “Preaching and the glory of God: The ministry of Martyn Lloyd-Jones” http://www.proctrust.org.uk/resources/conference/Evangelical+Ministry+Assembly+2014

Stevens, John. “1966 And All That: Reflections On Evangelical Unity Fifty Years After The Public Disagreement Between Martyn Lloyd-Jones And John Stott”

http://www.john-stevens.com/2016/10/1966-and-all-that-reflections-on.html

http://www.john-stevens.com/2012/11/anglican-free-church-rejoicing-in.html

Advertisements Share this: