I spent last week in a place I love. I love running there like no other place, because running there means I get to enjoy shaded trails under towering trees, and stop to drink in sweeping vistas of mountain ranges covered in hardwoods and pines. I can run longer and breathe easier in this place of magnificent trees. (Well, maybe not physically breathe easier because of the elevation, but there’s an emotional breath that comes more easily to me when I’m there.)

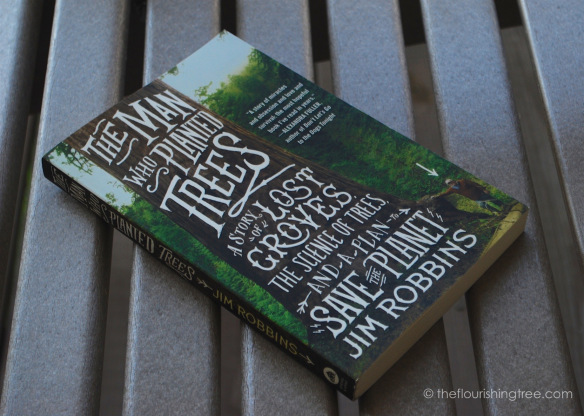

So when I imagine a world without trees, my heart catches, and I think of this beloved mountain place. I cannot let myself imagine it without its crown of trees. You might wonder why I would even try to imagine a world without trees. Well, because a book I recently read, The Man Who Planted Trees by Jim Robbins, asked me to do just that.

I hope you’ll read it. If possible, I hope you’ll read it outside or at a window where you can look out and see trees you love. The book is a hopeful, accessible examination of the science of trees, their intricate connection to the health of our planet and to our own health as humans, and efforts to counter the threats to their survival.

Robbins’ book focuses on David Milarch (pictured on the cover with an arrow pointing to him so you don’t miss him standing next to a giant among trees). Calling Milarch a tree enthusiast doesn’t come close to describing his passion for trees. He could have come across as crazy or eccentric after a near death experience brought him an urgent message from angels that the world’s trees were in danger. Robbins, a science writer, has trouble calling them angels. But I’m pretty sure that’s what they were. And, despite any doubts, Robbins writes of Milarch’s experiences, plans, and efforts with respect.

A few months after Milarch’s near death experience, angels visited him again and charged him with an intricate plan to save the world’s trees by cloning the best of them. Sound like fantasy or science fiction or hocus pocus to you? I can appreciate Robbins’ deft handling of the intricacies of Milarch’s story as he interweaves the science of trees, Milarch’s plans for their survival, and stories of individual trees.

I’ve written before about one of those trees, Prometheus, the oldest known bristlecone pine that was murdered, er, I mean cut down so a researcher could count its rings to see how old it was (more than 5,000 years old, which turned out to be the oldest known of its kind). Reading about Prometheus again broke my heart and reminded me I have yet to travel to eastern Nevada to see the remaining bristlecone pines. And I live a whole heck of a lot closer to them now than I did when I first dreamed of visiting them.

Milarch has spent years searching for what he calls champion trees, trees that are the tallest or largest or in other ways the best of their kind. He believes there’s something special encoded in their DNA that makes them thrive, and he wants to capture their DNA by cloning them before it’s too late. Before disease, fire, humans, or climate change take their lives.

He couldn’t do all of this alone of course, and he was a founding force behind the Archangel Ancient Tree Archive. Their work is inspiring, and I hope you’ll take a few moments to check out their story—on their website or in the book. Whichever you read, I hope you’ll come back here and let me know your reactions in the comments below.

I’ll leave you with this thought from William Blake (The Letters, 1799):

Share this:The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing that stands in the way. Some see Nature all ridicule and deformity, and some scarce see Nature at all. But to the eyes of the man of imagination, Nature is Imagination itself.

- More