The biggest issues we face today are the flat-lining of the Australian and most western economies after decades of neo-liberal pro-market, anti-worker policies; and the refusal of right-wing politicians to allow even the possibility of a consensus for dealing with global warming.

Yet the biggest, the dominant issue in Australian Lit. is clearly what it means to be an Australian – Anglo, Indigenous, or otherwise – in this land we whites stole from its Indigenous inhabitants, the oldest continuing civilization on Earth. And which by the way, we continue to steal by all the artificial constraints State and Federal governments put around Native Title determinations when the graceful thing to do after the Mabo judgement would have been to declare all Crown land Indigenous and to negotiate with the traditional owners using that as the starting point.

This blog was started to investigate notions of Australianness, so I would say that, but look at who is prominent in Aust.Lit today and what books are receiving the most attention. None is about the failure of the welfare state or the casualization of work or the disappearance of free education or the obscene wealth of the very rich, and very few are about climate change. It is a subject for another post, the question of which writers at the height of their powers today, clearly stand head and shoulders above their fellows, but I would suggest three names, Kim Scott, Alexis Wright and Chris Tsialkos, and two of those are Indigenous and the third, Tsialkos is concerned to investigate Australianness from his own non-Anglo, non-straight background.

Taboo (2017) is both personal for Kim Scott and political. Personal in that it is a continuation of his exploration of his roots as a Wirlomin Noongar man, a sequel to the story he began telling in Benang (1999), and political in that he uses the return of the Wirlomin to the site of the Cocanarup Massacre and the reaction of the current (fictionalised) owners of Kocanarup Station as a metaphor for how whites of good intentions everywhere struggle to recognise the depth of the ongoing harm that they are party to.

Noongar: those Indigenous people whose country is all the south-western portion of Western Australia (from south of Geraldton to west of Esperance).

Wirlomin: the south-easternmost of 14 language groups making up the Noongar. Their country is centred on the present-day towns of Ravensthorpe and Hopetoun.

For maps of Australian Indigenous language groups see the ‘Aboriginal Australia’ page above (or here). The AIATSIS map labels the Wirlomin region as ‘Minang’.

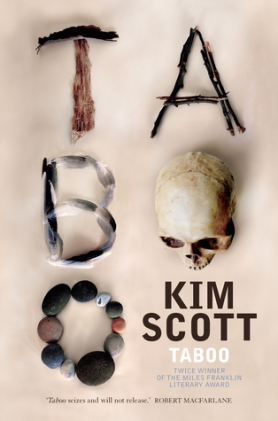

And finally, that cover. I have no religion, nor any thoughts about spiritualism or life after death, and I hope that when I am dead my body is rendered into compost. But that doesn’t mean that I think images of dead people should be used as decorations on book covers. And given the enormous efforts of Indigenous people over a long period to have the bones of their ancestors returned from museums and given a proper burial, I think it is doubly inappropriate that a skull should be used in this way an the cover of this book.

In fact, despite my great age and years of long-distance truck driving, I have not only never seen a dead person, I avoid seeing people killed on film or television (I certainly don’t find it entertaining!), and have never been the first or even an early attender at a traffic accident, except of course the ones I’ve been in myself. Which is by way of a lead in to the first (and last) scene in the book: a truck loaded with grain loses its brakes at the top of the short steep hill at the eastern end of Ravensthorpe’s main street, gathers speed, missing pedestrians and cars, looks headed towards the roadhouse at the bottom of the hill before veering to the right, towards the creek where, “slowed at last by deep, coarse sand”, it falls slowly onto its side. And as grain pours from the beached tipper trailer, there appears gradually … “Something like a skeleton, but not of bone. At least, not only bone. The limbs are timber. The skull is timber too, dark and burnished, and ivory dentures …”

Except here Ravensthorpe is called Kepalup (in Benang it was Gebalup), Hopetoun 30 km south on the coast is Hopetown and Albany, the main regional centre, 300 km west along the WA south coast, is King George Town (as it was in That Deadman Dance). Other nearby towns, Esperance and Lake Grace for example, keep their names and Perth is just the City. Kocanarup is now owned by the overtly Christian Hortons – Dan, a widower and his brother Malcolm. In the 1880s, at the time of the massacre, it was owned by the Dunns (Dones in Benang).

Dan Horton’s late wife Janet had been a prime mover in the establishment of a ‘Peace Park’ at Kepalup (which may stand in for the Kukenarup Memorial which overlooks Cocanarup Station, 15 km west of Ravensthorpe). A party of Wirlomin, mostly elderly, mostly from King George Town, camp at the Hopetown caravan park by the sea for a retreat, for some of them to dry out, to prepare for the official opening of the Peace Park.

Tilly, the central character is a student at a private girls school in Perth, on scholarship. She is the daughter of a white mother and a Wirlomin father, Jim who has recently died in jail where he had been leading the revival of Wirlomin language and culture. As a baby, till reclaimed by her mother, she was the foster daughter of Dan and Janet Horton.

Tilly comes down on the bus to Lake Grace where she is met by her father’s cousins, twins Gerald and Gerrard Coolman – descendants of the Coolamons of Benang – one who had been in jail with her father and is now dry and a leader of the Wirlomin revival and one who is not, and they continue on to Kokanarup, to meet Dan Horton and to walk around the vaguely defined sites of the massacre up till now treated as taboo. After a night as guests at the Station they go on down to Hopetown and meet up with the others for the retreat.

All the people are carefully, lovingly even described and we get to know them as they tentatively reclaim the language that was forbidden to them when the older ones were sent away “to the mission” as children, and nearly lost, and as they slowly reclaim the springs and creeks and hills and stones of the massacre site. And so Tilly, by upbringing and education a stranger but still a loved family member, learns the words and sites of her people as Scott must have done too when he began the long journey whose beginning is described in Kayang and Me.

For a while, the middle section of the book, we go back. Tilly starts seeing her father, dying in jail, runs away from her mother, gets in harm’s way, is rescued. A malign presence, a large white man, is in her life, in her nightmares, in the lives of many of the people. And in the third, final section he’s in Kepalup.

Benang, in particular, was a poetic work. Taboo is much more plainly written, but that is also its power.

Kim Scott, Taboo, Picador, Sydney, 2017

see also:

The Cocanarup Massacre, my post based on Kim Scott’s source material (here)

Lisa at ANZLitLovers’ review of Taboo (here)

My reviews of Kim Scott’s earlier works –

True Country, 1993 (here)

Benang, 1999 (here)

Kayang and Me, 2005 (here)

That Deadman Dance, 2010 (here)