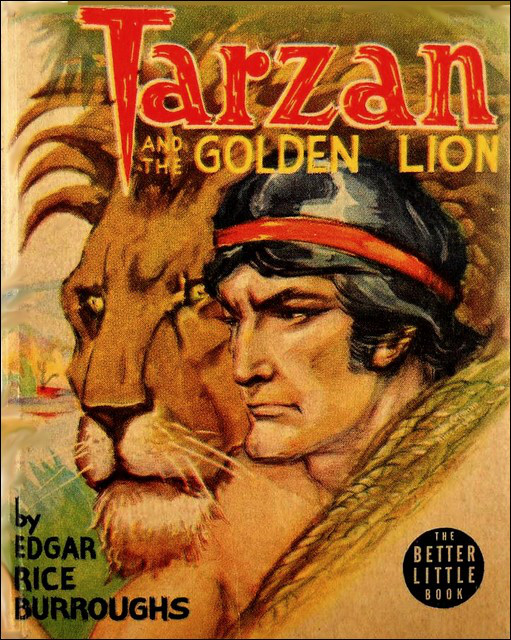

The appeal of Tarzan is straightforward. He is an English peer raised by anthropoid apes to become an immortal jungle adventurer. Tarzan is super-strong and is curious about everything. He can talk to animals. He has access to fabulous wealth. According to Philip José Farmer, Tarzan is totally free of neurosis and eventually will travel back in time and on to Alpha Centauri. In short, he’s someone you would love to be. Or at least someone I’d love to be.

That’s part of why I’m into Edgar Rice Burroughs’s novels about him as well as other authors’ Tarzan novels. They can be strange and fun. The antiquated story-telling style can be charming. Recently I read Tarzan and the Golden Lion. Here, I will consider its merits in light of an important fact known to all Wold Newtonians: Tarzan is real.

PART I: TARZAN IS REAL.

In 1972, Farmer sought him out (watch above) and interviewed Lord Greystoke for Esquire. (Article pay-walled). Burroughs and Tarzan’s other chroniclers have written fiction based on a real man’s life. In Tarzan Alive (1972), Farmer writes that ERB got a hold of Tarzan’s father’s diary from the colonial office in Nigeria and based the first work on this. Later Lord Greystoke himself contacted Burroughs with more accurate information about himself.

Robin Maxwell presents an alternative though perhaps complementary narrative in Jane: the Woman Who Loved Tarzan (2012). According to Maxwell, Burroughs met the real Lord and Lady Greystoke when the they visited Chicago for Lady Greystoke to give a scientific lecture. Lady Greystoke’s lecture fell flat with the scientific community, but she peaked Burroughs’ interest. She stayed up all night recounting the legend to him.

I say these accounts are complementary because it’s possible that Burroughs recorded Lady Greystoke’s account that night in Chicago and then sought out Greystoke Sr.’s journal. In either event, Burroughs didn’t invent Tarzan and Tarzan isn’t wholly responsible for the content of the adventures in which he stars.

PART II: BURROUGHS AS A TALENTED BUT FLAWED BIOGRAPHER.

One would be remiss not to acknowledge Burroughs’ talent. He earned the title “Master of Adventure” because he could spin a yarn. If it’s true, as Maxwell posits, that Lady Greystoke placed faith in Burroughs’ narrative abilities, then she certainly chose a talented scribe to tell the tales of her and her most exceptional husband.

The problem is that Burroughs knew very little about Africa, or its flora, fauna, geography and peoples. He was in the habit of making things up. As Farmer notes, the original magazine printing of Tarzan of the Apes referred to Sheeta the tiger. In the subsequent hardcover and in later editions, this was to be replaced with Sheeta the leopard as tigers do not live in Africa. Eight books later, Burroughs still has to retcon his zoology. In Golden Lion, the ninth Tarzan novel, the narrator explains that references to Bara the deer in earlier novels were actually references to antelopes. Like tigers, deer are absent from Africa.

Worse than Burroughs’ topical ignorance was that he had some racist ideas that were in tune with what a lot of white people believed back then. It’s accurate to say that he was a white man of his time. But it’s also accurate to say that a majority of his educated white contemporaries did not believe that African people had the capacity for self-government, whether they personally entertained race hatred or not. Burroughs spun Lord and Lady Greystoke’s lives into fine adventures but in the process polluted the stories with racist ideas.

PART III: TARZAN AND THE GOLDEN LION.

The above background is the context for this review. My experience with Tarzan and the Golden Lion was that it was a kind of cool novel but Burroughs got in the way of my full enjoyment of it. That’s not to say it’s all bad.

Golden Lion has a lot of what’s great about Tarzan in it. Burroughs’ Tarzan is at his best when he’s amusing himself by doing something uncanny involving animals. His hobbies are usually a little violent. The novel opens with Tarzan raising an orphaned lion cub, using a dog that lost her pups to suckle it. Tarzan is a delicious pervert: when he teaches the lion to eat meat, it is only off a manikin’s neck and only when Tarzan instructs the lion to, “kill.”

Tarzan makes a welcome return to the lost city of Opar and his relationship with its high priestess deepens. (He and Jane had recently expended their fortune in support the Entente in WW1 and Tarzan goes to seek out the Atlantean treasure vaults beneath the city). Lost cities and peoples are a major charm of Burroughs’ Tarzan oeuvre and Opar is the original. That said, I wish there were more world-building about Opar in this book. By Golden Lion, the Tarzan reader hasn’t learned anything new about Opar in seven books. It’s just a place Tarzan goes sometimes.

One neat addition to the world of Tarzan is a Spanish actor recruited to impersonate Tarzan by a crew of ne’er-do-wells. The ne’er-do-wells’ goal is to use the fake Tarzan to get gold from Opar. I’m not sure how that was supposed to work, but that might not be important to the story. The fake Tarzan is used in a comedy of errors sort of way. These parts of the novel are generally pretty funny.

The aforementioned parts of the novel mostly work and are a good time. But the real reason I was excited to read the book was that I was aware that Tarzan encounters a race of war-like intelligent gorillas (in ape-speak “Bolgani,” the same word used for normal gorillas) who have a civilization that is blocked off from the rest of the world by Opar. (Farmer theorized these Bolgani were actually a lost species of pithecanthropus). Talking apes and fresh lost worlds! This is the sort of thing one reads Tarzan for.

The economy of Bolgani’s kingdom was based on the slavery of race of stoop-shouldered and dark-skinned apish people with great prognathous faces. They are stupid, cowardly, and servile. They refuse to fight for their freedom when Tarzan seeks to organize them.

I’m not sure if a slave race of ape-people who are mentally inferior is bad form in and of itself, but in the context of this novel, it definitely is. The narrative didn’t make much of a cognitive distinction between these ape-people and black Africans. The characters refer to these folks as “gomangani,” which is the ape-speak word for black Africans. This feature of the plot borders on racist propaganda.

Of course, Tarzan liberates these people because he’s Tarzan and he (selectively) hates slavery. (See for counterexample Tarzan and the Ant Men). But he leaves behind a formerly enslaved British man as the new king of the ape-people. Tarzan’s reasoning is that the ape-people have no capacity for self-government. His solution is to saddle this old dude with the proverbial white man’s burden.

PART IV: WOLD NEWTONIAN EXEGESIS

Getting back to Tarzan being real: in chapter 13 of Tarzan Alive, Farmer toys with a few different theories of who these ape-people could be. One theory he puts forward was that they might be hybrids between modern humans and the pithecanthropoid Bolgani. To me, it looks like Farmer was trying to walk a tightrope here between Burroughs’ straightforwardly racist plot element and developing a non-racist, scientifically-plausible exegesis of the text. Farmer devotes a few pages to historical and physical reasons these hybrids could not be derived from Khoisan- or Bantu-speaking peoples. He goes as far as to say that any mental disabilities these folks have are the result of oppressive social conditions rather than biological inferiority.

Farmer’s exegesis is fascinating but I think he knew in his heart of hearts that the existence of these “gomangani,” at least as described by Burroughs, was a racist fantasy. Farmer begins his exegesis by noting these folks might just be an “exotic element” added by Burroughs. Plus he spent space addressing their alleged “mental deficiency” and went to lengths to disconnect these “gomangani” from the modern humans living in Africa today.

The hypothesis I would add to this discussion is the idea that if the Bolgani–pithecanthropi practice slavery, that the slaves are likely the same species of pithecanthropus as Bolgani. The physical difference between slave and master can be explained, at least in part, by generations of selective breeding combined with pervasive malnutrition among the slaves.

If Farmer was correct about Bolgani-pithecanthropus and their is merit to my hypothesis, this raises a further question: are these pithecanthropi related to the Woz-Don and Ho-Don of Pal-ul-Don?

CONCLUSION

As the foolish amount of time I spent writing and editing this blog post attests, I got really hung up on the racist depiction of Bolgani‘s slaves in Tarzan and the Golden Lion and it kept me from fully enjoying the novel. I think it could have been 100% fun if Burroughs didn’t see a need to draw similarities between the servile ape slaves and black Africans. But because of this flaw, the book left me fixated on this point rather than what was otherwise a cool adventure. I enjoyed Farmer’s exegesis about these slaves, but I think they are likely made up or embellished. I would really only recommend this book to other Tarzan, pulp fiction or Lost World fiction fanatics.

Advertisements Share this: