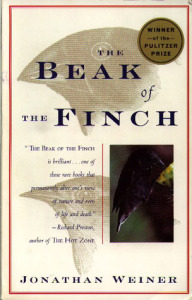

In 1995, Jonathan Weiner’s The Beak of the Finch (1994) won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction. As one of the most beautifully written books I have read on the topic of evolutionary biology, it is clear to me why Weiner won this accolade.

The Beak of the Finch – book cover

The Beak of the Finch – book cover

Weiner’s book follows Peter and Rosemary Grant – biologists, as well as husband and wife who have dedicated their careers for understanding evolution. Every year for twenty years, The Grants have travelled to Daphne Major, an island in the Galapagos archipelago in order to study the different species of finches that live there. The archipelago and its flora and fauna are significant in the field of evolutionary biology. Indeed, they may be regarded as the birthplace of this field of science. In 1835, Charles Darwin himself visited the Galapagos while travelling on the HMS Beagle. His observations and interactions with the plants and animals are thought to be the catalyst for his groundbreaking masterpiece The Origin of Species.

Peter and Rosemary Grant collecting data at Daphne Major. Image credit K.T.Grant – New York Times 2014

Peter and Rosemary Grant collecting data at Daphne Major. Image credit K.T.Grant – New York Times 2014

Over twenty years, The Grants, measured and recorded the sizes of the finches beaks as well as eating, breeding and nesting habits. Through Weiner’s evocative writing, the readers feel as if they are on the island alongside The Grants, experiencing their joys and sorrows as they spend months living rough to collect the data. The hand drawn sketches throughout the book by their daughter, Thalia Grant adds a ‘field-journal’ element to the book. Her drawing skills were honed while being home-schooled on Daphne Major by her parents.

The island of Daphne Major in the Galapagos. Image credit: Parer and Parer-Cook – New York Times 2014

The island of Daphne Major in the Galapagos. Image credit: Parer and Parer-Cook – New York Times 2014

The author does not ignore the significance of Darwin. Throughout the book, Weiner draws on Darwin’s own field notes, letters and quotes which provide valuable insight into how he developed the theory of evolution. So much so that it feels like the reader is having a conversation with the man himself. Neither does Weiner gloss over some of the weaknesses of Darwin’s theory, such as his belief that evolution is a slow process which manifests only after many generations.

Indeed in The Beak of the Finch, the data gathered by The Grants over the past two decades demonstrates that evolution can be a dynamic and rapid process. For instance, The Grants noted a shift in the average size of the beaks in the finches born after a severe drought or an intense wet season. Within each chapter, Weiner draws on a number of other researchers who are working with fish, moths and flies who have found similar trends to The Grants.

The reference to other research projects provides a refreshing break from The Grants and their finches as the book becomes repetitive in the middle with multiple references to the various species of finches on Daphne Major. Further, some readers have criticised Weiner for his foray into religion and philosophy towards the end of the book arguing that this inclusion is either unnecessary or superficial. Personally, I did not find this distracting as I think Weiner’s intention is to invite his readers to examine the relationship between religion and evolution themselves.

Despite the criticisms, The Beak of the Finch is a fantastic read. Weiner writing style achieves a great balance between adventure, emotion and it serves as a masterclass for those interested in science writing. It is a book that I would highly recommend to anyone, particularly students who are interested in understanding evolution or as a gentle introduction to Charles Darwin and The Origin of Species.

Advertisements Share this: