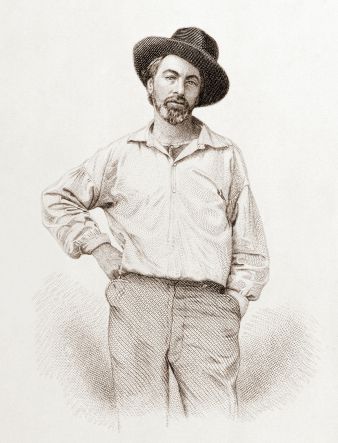

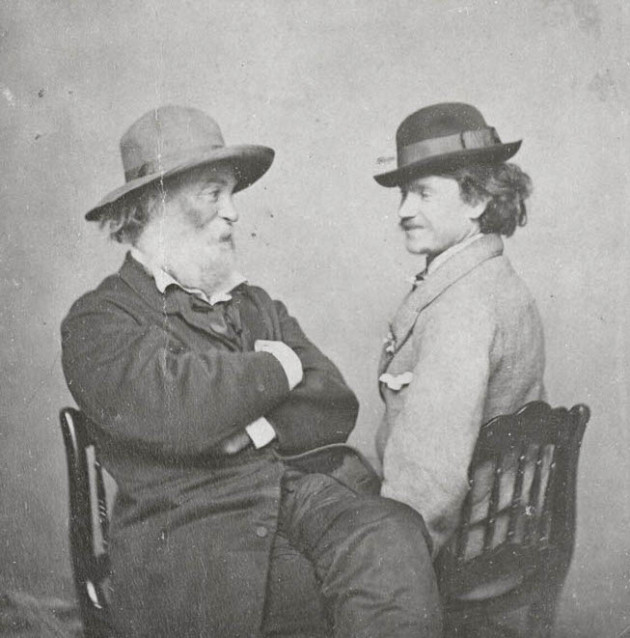

Walt Whitman in 1855 (ow, ow!)

Poets are among the strangest writers of all. I know because I am one. Endlessly curious about the depths of human emotion, inappropriately inquisitive, and heartily obsessed with both surface and interior, our ways of interacting with the world can really give people the wrong idea. But– hear ye– the endgame of our experimental behavior occurs on the page. I cannot pretend to know the full meaning of what it is to be built this way. But I shall try, using the poet Walt Whitman.

TIME: MID-CIVIL-WAR

PLACE: AMERICA

LAWS AND SOCIAL CUSTOMS: MEN + MEN = NO

MAIN CHARACTER: WALT WHITMAN, FATHER OF AMERICAN POETRY

SUPPORTING ROLE: PETER DOYLE, CONFEDERATE SOLDIER AND WHITMAN MUSE

It’s the 1800s, it’s the middle of the American Civil War, and Walt Whitman is slowly establishing himself as the most talented poet in American history. Europeans are wild about him, even President Abraham Lincoln would become a crazed fan. Whence did Whitman draw his inspiration for works that attracted fans both hippie and stately?

You guessed it: War.

“The blood of the world has fill’d me full—my theme isclear at last:

I hear from above, O pennant of war, your ironical call

and demand;”

-Whitman, “Song of the Banner at Day-Break”, 1865

In a delightful piece available here by scholar Angel Price of the University of Virginia, I learned that Whitman’s life was closely shaped by the happenings of the American Civil War, which in turn influenced his psychology and provided poetic fuel.

“I chant this chant of my silent soul, in the name of alldead soldiers.”

-Walt Whitman, 1865

Picture this: a young Walt Whitman, vagabond and self-proclaimed American Bard, listening to traumatized young soldiers after the American Civil War at their hospital bedsides, soaking in their stories, weaving them into verse for his 1865 work, Drum-Taps.

Oh, I have pictured it.

Whitman and war, you say? You thought he was all about dick innuendo and poems taking place at the entrance of the birth canal (see “Song of Myself,” section 49)?

“Whitman was patriotic but also free from society’s restrictions; he was not bound by class and reflected endless possibility within one’s self.”

-Angel Price, University of Virginia

Who was the liberal, freethinking, highly bisexual Whitman’s designated muse? Oh, just a former Confederate soldier Peter Doyle, who was quite cooperative with curious historians after Whitman’s death. In other words, we have a lot to go on here.

“Who you callin’ gay?” Walt Whitman (Northern Bard) and Peter Doyle (Confederate Soldier and Whitman muse), circa 1869.

Mostly, I found it sad that Doyle was clearly highly traumatized from his time spent in combat: he refused to talk about that aspect of his life with historians, ever. Wounded in the bloody, Union-won Battle of Antietam in Maryland, Whitman’s future muse sought to be discharged from the Confederate Army in 1862. No doubt he was weary both physically and mentally. Men typically seek to exit the service when they have seen one too many grisly things.

Whitman met Doyle when Doyle was working as a car conductor in Washington, D.C. But it wasn’t the typical taxi experience: it was holy. Peter Doyle described the encounter to a historian:

“You ask where I first met him? It is a curious story. We felt to each other at once. I was a conductor. Walt had his blanket it was thrown round his shoulders he seemed like an old sea-captain. He was the only passenger, it was a lonely night, so I thought I would go in and talk with him. Something in me made me do it and something in him drew me that way. He used to say there was something in me had the same effect on him”

-Peter Doyle, on first meeting Walt Whitman in 1865

Poets are observers. What we crave: that which is most human. Our personal relationships are more precious than our belongings. Whitman’s attachment to Doyle was not only personal, but historic: as a poet, you choose your muse both intuitively and consciously, and always very carefully. Whitman chose someone who had seen the worst of all human behavior, fought for the “wrong” side, and survived it.

Whitman himself confirms Doyle’s influence on not just Drum-Taps, but Leaves of Grass, which is considered a holy text in the world of poetry.

“[Pete and I] would walk together for miles and miles, never sated. Often we would go on for some time without a word, then talk—Pete a rod ahead or I a rod ahead…It was a great, a precious, a memorable experience. To get the ensemble of Leaves of Grass you have got to include such things as these—the walks, Pete’s friendship: yes, such things: they are absolutely necessary to the completion of the story.”

-Whitman, as told to historian Horace Traubel

To Peter Doyle, the Confederate veteran whose jaunts with Whitman inspired a book of poetry that moves me to tears and makes me want to throw up in the best possible way… cheers.

Share this: