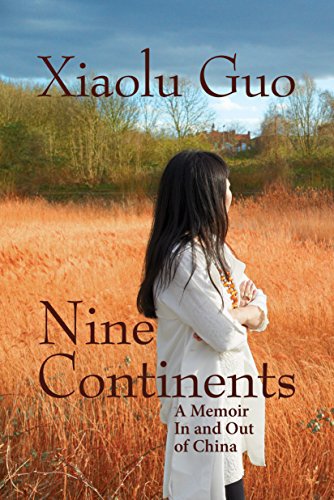

Your book Nine Continents (2017, also published in the UK with the title Once Upon A Time in the East: A Story of Growing up) is less a memoir than a collection of your personal myths. And it is a book about the transformative nature of art; about art as a means to escape, as something in-between different realities, something true and false at the same time. You paint yourself with the same colours of the orphans who were the protagonists of your favourite novels; like them, you will eventually turn out to be the hero of your own life.

We learn that, immediately after your birth in the early seventies, you were handed over by your biological parents to a peasant couple who lived in the nearby mountains. Two years later, those adopted parents, claiming they couldn’t feed you, handed you back to your paternal grandparents. In the fishing village of Shitang (literarily, Stone Pond), in Zhejiang province by the East China Sea, you were confronted with the remains of a feudal life style, where women as your grandmother – an unnamed, foot-bound, illiterate woman who had been sold into marriage when she was twelve years old – were regularly beaten by their alcoholic husbands.

Following your grandfather’s suicide, when you were almost seven years old, your biological parents came to Shitang to reclaim their daughter. Without much explanation, you are then taken by these strangers to live with them. In a communist compound in the industrial inland town of Wenling, you were beaten by your mother, ignored and harassed by your older brother and his friends; you were sexually assaulted by one of your father’s colleagues; and you had to undergo an abortion after an affair with one of your teachers.

You had your first opportunity to escape in 1993, when, from 7.000 applicants, you were one of eleven students accepted into Beijing’s Film Academy. Your university years were spent in the vigorous scene of Beijing’s artistic vanguard that followed the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. You voraciously read books and watch movies, you make friends, you take lovers – including one violent Chinese man -, you publish your first books. You take every chance you were given to educate yourself – only to be confronted, after graduation, with constant censorship of your movie scripts.

When you win the Chevening scholarship to study at the National Film and Television School in Beaconsfield, UK, you make clear to the reader that escaping once again would be the only step to take in these circumstances. You settle in London, you struggle to learn the language, and you finally become a successful published author who manages to write originally in English – a borrowed language, like a borrowed identity.

I must confess that, if I had read the paragraphs above, I would hardly have picked up your book. ‘Another misery memoir about the shortcomings of communist China’, I would have thought, ‘a shorter, less ambitious ‘Wild Swans’ for millennials.’ Or, even worse, I would have dismissed it as just another ‘Chinese Cinderella’ story, a self-indulgent memoir of a Chinese woman’s wrenching journey from Eastern hell to rose-tinted Western paradise.

Had I thought so, I would have been wrong, my dear. Firstly, because your book is less a memoir than a collection of anecdotes, a collection of san wen, small fragmentary stories. Secondly, because, unlike Chang’s memoir, your book has a fable-like quality – as we can infer from the British title ‘Once Upon A Time…’ – and your writing-style is more personal, blunt, rough. Thirdly, and more importantly, because, unlike Adeline Yen Mah’s memoir, your book manages to achieve a solid middle ground between never shying away from brutal facts, while at the same time never lapsing into self-pity.

Furthermore, unlike many memoirs of immigration that boil down to giving the reader a taste for a so-called exotic land while also reaffirming his conviction of so-called Western superiority, Nine Continents/ Once Upon A Time in the East does not romanticize England. You escaped state censorship – or self-censorship, the ‘shadow body’ in every Chinese artist -, only to find yourself alienated in new ways in the West.

Yours is not a journey to paradise; in fact, it is not even a journey you have already completed. “It seems to me that people decide to settle somewhere not because they love the place, but because they value and cherish what they have invested in it.” I love the beautiful image at the end of the book, when you realize that you have come full-circle, back to the very beginning of this journey: orphan, dislocated, angry. “I was my own home now.” There is no reconciliation, no forgiveness, no Pollyanna-like acceptance of the past. You never stop being a peasant warrior, and I quite like that.

If a reader comes into your book looking for the epic scope or the detachment of Chang’s prose, he will be disappointed. Some of your small stories are scarcely believable, and we have the feeling that you took the artistic licence to fill in the gaps between what you remembered and what your five-year-old self could never have grasped. At the time I was reading your book, I came upon a poem by American writer Jane Hirshfield, and it resonated with what I was feeling about your story (and about your way of telling it): “Transparent as glass, / the face of the child telling her story. / But how else learn the real, / if not by inventing what might lie outside it?” (‘Glass’, in Come, Thief, 2011). Yours is, after all, the coming-of-age story of a self-made artist, a portrait of the artist as a young Chinese woman. It is art, and artifice.

The story fragments assume a mythic quality: like the episode when a Taoist monk tells your grandmother that you were a peasant warrior set to travel the Nine Continents; or when your father explains to you the meaning of your family name, Guo (“It means ‘outside the first city wall’. In the old days, people built two layers of wall around their cities and Guo is the space between them. An in-between zone. That’s what our name means”); or the episode when you, still a young girl in Shitang, meet a group of art students on the beach and marvels at the fact that they can create beauty out of a grey, featureless seascape (“I was suddenly captivated by the girl’s imaginative act: that one could reshape a drab and colourless reality into a luminous world.”). Reshaping is as much what you do in this book as it is what you have done with your life.

Unlike Chang’s Wild Swans, your writing is unpolished, ruthless, and openly angry – as if you refused to wear down your voice’s sharp edges into a smooth pebble all too comfortable to the reader’s touch. I was reminded of another poem by Hirshfield: “One angle blunts, another sharpens. / Loss also: stone & knife” (Come, Thief, 2011). Yours is an all-encompassing anger, pointing East and West, a broken compass. If Xinran Xue were to capture your testimony, your voice would be better fitted to a collection of The Naughty Women of China. You are hard-hearted, restless, ambitious; your move to the arts was more than anything fuelled by anger.

Moreover, unlike Chang’s and Xinran’s privileged backgrounds, you came from the bottom of the social hierarchy. Illiterate and malnourished until the age of seven, yours is a story of a peasant girl desperate to escape poverty and violence. Furthermore, your family story is one of people who only had the chance to study and rise from the bottom of the social scale through the institutions and incentives of communist government. You are thus much more ambivalent about some aspects of China than Chang or Xinran. And you are angrier – as flawed and captivating as the Monkey King in Journey to the West, a classic Chinese novel whose fragments you use at the beginning of each chapter of your own personal journey to the West.

In fact, the great strength of your book lies in the fact that you manage to retain that ambivalence, never simplifying your conflicting relationships with China and with the West. As if you refused to settle down to a fixed opinion; as if you preferred to remain exiled, nomad, thrown in the middle of a multi-layered and ever-changing battle. If anything, I wish that you had explored this ambivalence even further, and fiercely; and I wish that you had told a more detailed story of your first years in the UK. What about the roads not taken? Or the new personal myths acquired in the new land? Maybe this is material for another book. While structured as a journey, Nine Continents’ myths are still very much rooted in the East: drenched in sea salt and in the scent of gardenias that persistently grow between dry rocks.

Yours truly,

J. 18th century depiction of Hua Mulan (花木蘭), legendary Chinese woman warrior

18th century depiction of Hua Mulan (花木蘭), legendary Chinese woman warrior

About the book“The girl is a peasant warrior”, the old monk announced. “She will cross the sea and travel to the Nine Continents.” – Xiaolu Guo, Nine Continents

“Silence was the way we communicated, a family tradition carried down to my brother and me from my parents and their parents (…) Never mention the tragedies, and never question them. Move on, get on with life, since you couldn’t change the fact of your birth.” – Xiaolu Guo, Nine Continents

“Of course, I felt their judgement was unfair. For me, ‘being pretentious’ was the complete opposite of ‘being intellectual’. A real intellectual hates empty pretension.” – Xiaolu Guo, Nine Continents

“While my parents had been with me, I had keenly felt their presence as an imposition – as if they were an uncomfortable shirt I had to wear pricking my skin, or hair constantly in my eyes blocking my vision (…) But as the days passed after their departure, a sense of nakedness returned to me, and their absence became another unwanted presence.” – Xiaolu Guo, Nine Continents

- Grove Press, 2017, 304 p. Goodreads

- Also published in the UK with the title Once Upon A Time in the East: A Story of Growing up, Vintage Books, 2017, 304 p. Goodreads

- My rating: 4 stars

- This book was kindly sent to me by Grove Press for review.