Recommended for 20th century history, astronomy or astrophysics, feminism, history of Harvard.

5/5 stars

Summary: Ms. Sobel weaves technical details, history, and personal stories together in this wonderful, intimate telling of the women who laid the foundations of modern astronomy and astrophysics.

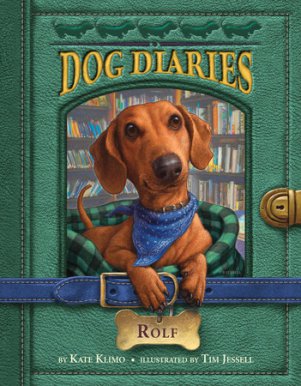

The hardcover copy of the book.

The hardcover copy of the book.

I devoured this book in the span of about 3 days. It was a great combination of things I love: feminism, history, and astronomy. I found myself growing attached to previously faceless names like Edward Pickering, Annie Jump Cannon, Cecilia Payne, Solon Bailey and dozens more. I read about their struggles with telescopes, funding, discrimination, war, disease, and (in many cases) each other.

I first noticed this book in my Amazon suggestions area. I had read “Hidden Figures” (and loved that as well) and this appeared as a suggestion. I didn’t buy it at the time but I noticed it just last week on my library’s shelves, available for checkout. I read this just before the solar eclipse and it seemed like the perfect time to read about astronomy.

I’ve always been vaguely interested in astronomy, but most of my life has been lived in sprawling metropolitan areas where good stargazing is damn near impossible due to light pollution. I had mostly given up on it until I went to Hawai’i in June 2016 and my husband and I trekked up to the observing station on Mauna Kea. Mauna Kea is one of the best stargazing locations in the world and we were lucky enough to get there on a moonless, mostly cloudless night. It was beautiful and re-kindled my interest in stargazing and astronomy, but pregnancy derailed that and put it on hold.

This book, reading about the passion of the people who discovered so much of our universe, had pretty much the same effect.

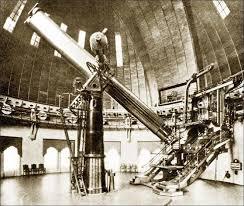

Ms. Sobel structures her tale chronologically, focusing on the “heyday” of Harvard star observations, before NASA, before the Smithsonian, before electronic computers and digital images. From the late 1800s to the mid 1900s, a period spanning a good 70 years, images of the stars were recorded on glass plates. I don’t say “photographs” because they weren’t always. These glass plates were analyzed, hour after hour, by dozens of women known as “computers.” These women did the legwork in cataloguing the heavens. Their work was relied upon by astronomers all over the world, asking to see their plates or spectral lines. It was a work full of tedium and detail, and without it our understanding of the universe would be so much shallower.

But the “computers” of Harvard did not stop there. They assigned names to the stars, classified them, teased out their magnitudes, sizes, composition, and location, and kept coming back for more. Henrietta Swan Leavitt’s work allows us to determine the distance of the stars, the size of the Milky Way, and the incredible distance of the other galaxies in the universe. Cecilia Payne was the first to discover that stars were primarily composed of hydrogen and helium, laying the first paving stone to understanding how they work. Williamina Fleming, Antonia Maury, and Annie Jump Cannon created the foundation of classification systems for the stars that are still used today.

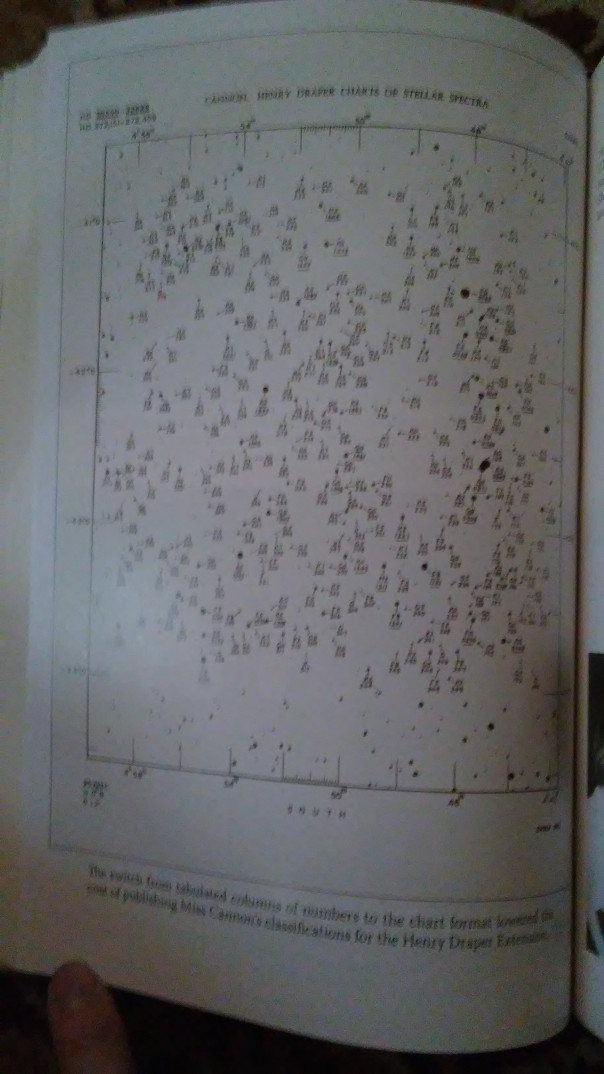

Text reads: The switch from tabulated columns of numbers to chart format lowered the cost of publishing Miss Cannon’s classifications for the Henry Draper Extension.

Text reads: The switch from tabulated columns of numbers to chart format lowered the cost of publishing Miss Cannon’s classifications for the Henry Draper Extension.

Women also funded a great portion of the Harvard Observatory’s star work, from Mrs. Anna Draper (with whom the book begins) creating a memorial in her husband’s name to Maria Mitchell’s various research fellowships to Annie Jump Cannon, donating her own money to a prize for women that lasts to this day. Catherine Wolfe Bruce contributed massive amounts of her own money to Harvard, funded the most impressive telescope of the time, and funded an award for astronomy that also continues to this day.

The book is full of the glass plates, but also glass ceilings and how they were broken. Cecilia Payne-Gaposhkin was the first woman at Harvard to receive a PhD in astronomy and the first to earn the title of Phillips Astronomer. Mina Fleming was the first woman to be granted an official title. Annie Jump Cannon was the first woman to win the Draper Medal and to be listed as the William Cranch Bond Astronomer. There is also a very brief note that the 19th amendment, recognizing women’s right to vote was passed during this time period.

Ms. Sobel’s writing style is pretty accessible overall. There are a lot of people and a lot of names; it can be hard to follow or remember who did what at times since there are multiple “plots” to follow. If that’s something that trips you up, keep it in mind while reading this books. Ms. Sobel also does not provide too much in the way of modern-day knowledge to contextualize the discoveries and theories of the day. It helps keep you in the moment, but I had to fight the urge to look up the Magellanic clouds to see whose theory on them was right.

Ultimately, it’s a fascinating read and an excellent telling of ‘untold history.’ I love works that challenge the way we think about history, so often influenced by pop culture, incorrect and long-debunked conclusions, or our own perceptions. The women’s names in this story are ones that are very well known to people who are familiar with the history of astronomy, so it’s not quite as obscure or perception-shattering as “Hidden Figures” for example. However, it is still a wonderful deep dive into the history of the Harvard Observatory, and the women whose money and work formed the bedrock of modern astronomy.

Advertisements Share this: