One of the most pivotal Plantagenet reigns was that of Edward III between 1327 and 1377. Part of that is due to its sheer length – 50 years would be a remarkable reign today, so imagine how that felt in the 14th century. Another facet is everything that was accomplished during that time, not least of which were strategic victories against the French at Crecy and Poitiers. But its greatest legacy was the dynasty that Edward left behind, one which in some respects was night and day from the England which he inherited as an adolescent, and in others was an eerie mirror image of it.

Today, Edward is most frequently referenced as the patriarch of the Wars of the Roses given that the feuding families vying for the throne in the 15th century based their claim, in part, based on how they claimed descent from him. Importantly, those fractures were evident as early on as his death in 1377, some 80 years before the first battle of the civil war broke out. Even more significantly, that split could be seen as far back as the days of his accession, though it would have been impossible to foretell how the dynasty would shake out.

The coup of 1326

The coup of 1326

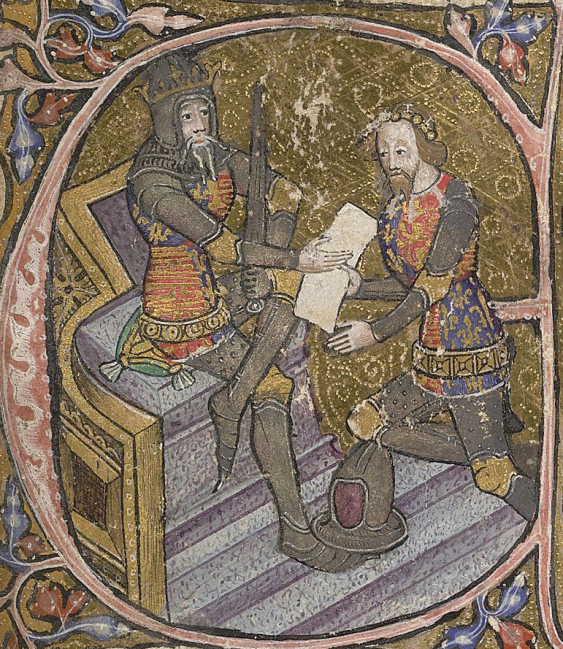

Edward came to this throw via a coup despite being the eldest son of the reigning monarch, Edward II. After nearly two decades of unhappy marriage to the King of England, Isabelle of France aligned herself with her lover, Roger Mortimer, and overthrew her husband, displacing him with their 14-year-old son, Prince Edward.

Still a minor when he came to the throne, the young king was in no position to rule for himself, nor to have much of a say in how his mother and Mortimer handled affairs. Which is not to say he didn’t have an opinion – the assassination of his father a few months after his forced abdication undoubtedly stayed stayed with him and sowed the seeds of discord for how Mortimer was controlling his mother and his nobles.

In 1330, nearly 18, Edward staged his own coup after the birth of his eldest son, another Prince Edward, and Mortimer was executed. Mortimer’s eldest son, Sir Edmund Mortimer, never inherited his father’s earldom of March, but it was regained by his son, another Roger, in 1354. That Roger’s son, Edmund Mortimer, 3rd Earl of March, changed the game for his family by marrying Edward III’s granddaughter, Philippa, only child of Prince Lionel, Duke of Clarence. Their grandson would become Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, who many believed to be the rightful king of England when Lancaster usurped the throne in 1399, and it was via this particular claim that Richard, Duke of York would claim the throne during the Wars of the Roses in 1460. But we’ll get there.

By the 1370s, the halcyon days of Edward III’s reign were over. His multitude of children with his wife, Philippa of Hainaut, were grown and more than a few were outlived by their parents. Philippa had died of an extended illness in 1369 and Edward had taken a long-time mistress, Alice Perrers, who was viewed by his court and the public as an opportunistic harlot – a outlook that may not have been entirely fair, but we’ll get to that some other time.

There is some evidence that Edward had begun to suffer a series of strokes in the last years of his life, undermining his mental health and ability to govern, however it’s impossible to offer a conclusive medical diagnosis. What is clear is that he was highly dependent on those around him in old age and became somewhat feeble. He believed he was going die years before he actually did and he was effectively unable to govern, leaving a power vacuum that was filled not only by his son, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, but also by those looking to profit from the chaos.

The last Parliament that Edward was attended was that held in 1373, however it was the so-called “Good Parliament” of 1376 that would mark the last phase of his reign and set the stage for after his death. It’s important to note that throughout this period of time it was unclear how soon Edward would die except that it was expected imminently, underlying every action with a sense of uncertainty and urgency. The notion of this parliamentary session was based on deep dissatisfaction with the coterie of followers who surrounded the King, hangers-on who were regarded as opportunistic and manipulative of Edward in his old age. It was catalyzed by losses in France and a disruption to the natural order of succession that was prompted by a dying Prince of Wales and the controversial leadership of Lancaster.

The great irony of all of this is that the reformist wave was led, in part, by Edmund Mortimer, great-grandson of the same Roger who had had the audacity to seduce Edward’s mother and rule his government 50 years before. The same corruption and hubris with which Edward had brought him down, he now stood accused of by his heir.

The session ended in Lancaster calling for an adjournment – essentially putting a pin in the issue as the calls for reform were too loud to ignore and too significant to address. Edward was mostly kept in the dark about what was happening at Westminster, but news still reached him that there had been calls for his deposition, a situation that could only have reminded him of his father and made him fear the worst.

Edward III and the Black Prince

Edward III and the Black Prince

He requested that he be taken to see his eldest son, the Prince of Wales, who had been suffering from a delibitating disease for the last seven years. The Prince of Wales, otherwise known as the “Black Prince” was a military hero at the apex of his career and of all of Edward’s sons, his favorite. He had married for love in 1361 to an Englishwoman, Joan of Kent, and had two sons, only the youngest of whom, Richard, was still living.

Edward brought his son back to the Palace of Westminster and was with him when he died, promising to honor one of the Prince’s last wishes, which was that his father look out for the young Prince Richard. It’s difficult to overstate what a disaster the Black Prince’s death was – not only was he an incredibly beloved figure with the public, but in his absence England was left with a dying old man on the throne and a child for an heir. The charges of corruption and dissatisfaction were unlikely to be addressed during a minority regime.

Meanwhile, Alice had been called out in the Good Parliament and was forced to leave Edward’s side. Afraid for her life, not to mention her quality of life, after Edward’s death, Alice had secretly married a man by the name of William Windsor. The marriage had been kept under wraps, but when it came to light, Alice was forced to defend it by saying she was no longer Edward’s mistress and hadn’t been for some time – as such, it’s safe to say she left the King abruptly and without warning. Edward was left grappling with the loss of a beloved son and the woman he loved at the same time.

By the end of September 1376, Edward fell ill once more and within a few days wrote his will, generally a sign that the end was near. Among his requests was naming Richard his heir and leaving him his finest bed and all of its hangings (the expense of beds in the Middle Ages made them valuable commodities), as well as bequeathing a sizable amount of money to his daughter-in-law, the Dowager Princess of Wales. He left his favorite daughter, Isabella, Countess of Bedford, an annual income until her daughters were married and the rest was divvied up among a selection of his sons.

His son, Lionel, Duke of Clarence, was already dead, but he pointedly disinherited Lionel’s daughter, Philippa, who had married Edmund Mortimer and just made problems for Edward during the Good Parliament. It was a final petty act for a man who despised the Mortimer family, but one which would have an enormous impact on English history for the next century.

Yet another request was to bring Alice back to him, which she did, believing the end was near. In fact, Edward lived another eight months, changing the optics of the reunion from a dying man’s last wish to say goodbye to a skirting of government reforms.

His last ceremony was St. George’s Day on April 23, 1377 at Windsor Castle. He knighted two of his grandsons, Richard, his heir, and Lancaster’s eldest son, Henry of Bolingbroke. The irony of that isn’t lost on us today, for the two cousins would grow into bitter rivals over the course of Richard’s reign, leading to Henry’s usurpation of Richard’s throne 22 years later and the founding of the royal House of Lancaster. At the time, it was merely an acknowledgement of the next generation of Plantagenet men.

Edward then moved to Sheen and prepared for his death. At one point he reportedly summoned random Londoners to him and asked them to create a large candle bearing the arms of Lancaster and burn it in front a statue of the Virgin Mary at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Whether this had some symbolism for Edward is unclear, but his contemporaries believed he had gone mad. Few visited him, but for those who did, it appears they took their leave of him in advance instead of keeping vigil. When Alice left, she is reported to have taken the rings from his fingers when she did, a tale that has only further blackened her reputation.

He finally succumbed on June 21, 1377 in the presence of a sole priest. His last words were, “Jesus, have pity.” He is still buried today in Westminster Abbey.

The throne passed to his young grandson and a minority government was established, which successfully managed to see Richard into adulthood. His deposition in 1399 by his cousin, Henry of Bolingbroke (Henry IV), saw the rise of Lancaster and the so-called end to Plantagenet, however it’s worth considering the plight of Edward’s disinherited granddaughter, Philippa. The issue was never Philippa herself, but rather the sons she might have. And indeed, that claim to the throne, one which by birth trumped that of the Lancastrians via King Edward, was passed on to her son, grandson and, finally, Richard, Duke of York in the 15th century.

York would be mocked when he assumed the surname “Plantagenet” during the reign of Henry IV’s grandson, Henry VI, and guarded suspiciously for what he meant by using it. The meaning, of course, was clear – it was an allusion to Philippa and Lionel and Edward III. A nod to a blood inheritance that may have been legally set aside, but which would continue to haunt the English government until York’s son, Edward IV, was crowned in 1461, nearly a century later.

Share this: