The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time was released in 1998 to a reception unlike anything that came before. To a skeptical crowd, Nintendo proved they were still relevant in a gaming scene that was then dominated by Sony, their new rival, by releasing what is considered to this day the medium’s greatest achievement. Even though Nintendo was naturally interested in creating a follow-up to this landmark title, they themselves knew it would be a tough act to follow. As one of the directors of Ocarina of Time, Eiji Aonuma, noticed, they were “faced with the very difficult question of just what kind of game could follow Ocarina of Time and its worldwide sales of seven million units”.

Nonetheless, requests for a sequel ensued, and Nintendo knew it would be for the best to create one soon while members of the gaming sphere were still talking about Ocarina of Time. Shigeru Miyamoto proposed a concept akin to the second quest of The Legend of Zelda wherein the dungeons of Ocarina of Time were rearranged while retaining the same plotline. It was to take the form of an expansion disk entitled Ura Zelda, roughly meaning “Reverse Side Zelda”. The unit was planned to utilize the Nintendo 64DD, a peripheral device intended to be attached to the bottom of the Nintendo 64.

However, Mr. Aonuma believed that the dungeons in Ocarina of Time complemented the story and the gameplay in such a way that replacing them wouldn’t work at all. Without Mr. Miyamoto’s knowledge, Mr. Aonuma began working on dungeons and environments independent from the tentative Ura Zelda. After some time passed, Mr. Aonuma summoned the courage to approach his boss with a proposal of his own. He asked permission to stop work on Ura Zelda to create an original game that would treat audiences to an entirely new experience. Mr. Miyamoto was surprised, but offered Mr. Aonuma a deal; he could direct a brand new Zelda installment, but it had to be completed in one year. Even those not in the industry would realize a problem with this deadline. By this point in gaming history, development cycles lengthened as technology became more sophisticated. For the sake of comparison, Link’s Awakening, the then-newest 2D installment, took eighteen months to create. Ocarina of Time, on the other hand, spent four years in development. The idea of creating another 3D installment in less time than a Game Boy title seemed impossible.

Even with the odds massively stacked against him, Mr. Aonuma accepted the task. Fortunately, Mr. Miyamoto wasn’t going to leave his colleague to his own devices. He allowed Mr. Aonuma to reuse art assets and character models from Ocarina of Time, which by itself significantly cut down on the amount of work they would have to do. Moreover, Yoshiaki Koizumi, who had made a name for himself writing the scenario for Link’s Awakening and serving as one of the five co-directors of Ocarina of Time, was asked by Mr. Miyamoto to aid Mr. Aonuma in this project. Mr. Koizumi approached with a game concept he came up with while daydreaming: the ability to rewind time so the player may revisit the same levels, eventually unlocking new content through their successive experiences. As time travel was a concept featured heavily in Ocarina of Time, this would appear to be a perfect fit for the series.

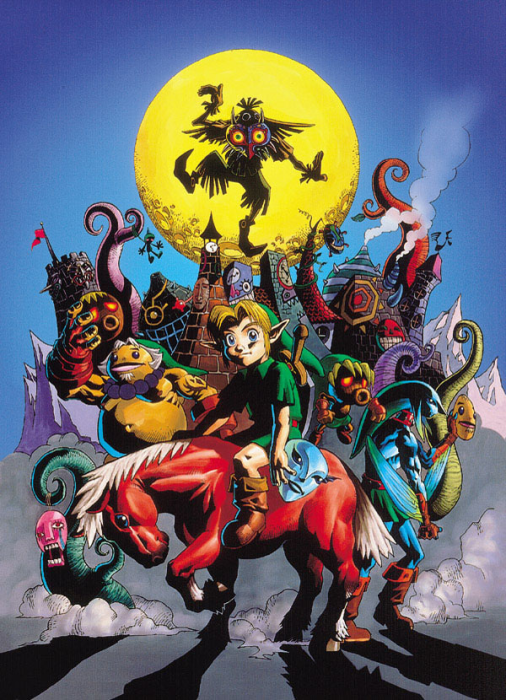

Despite all of the measures taken to cut development time, Mr. Aonuma was feeling the pressure of the rapidly approaching deadline. At one point, he even had a nightmare wherein he was attacked by characters in the game. Mr. Miyamoto took notice of this and graciously allowed Mr. Aonuma to take extra time to get the project done. To the former’s surprise, Mr. Aonuma expressed his determination to fulfill his promise, and he and his team soldiered onwards. As if to punctuate this, his nightmare even inspired the creation of a cutscene in the final product. The team took all of the emotions they carried throughout this arduous journey, and used them to help craft their work. Finally, as promised, the game was completed after one year, seeing its official release in 2000. Though it began life as Zelda: Gaiden, the game evolved into a full-fledged entry in its own right by the name The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask. Though it sold millions of copies and garnered a lot of critical acclaim, Majora’s Mask was overshadowed somewhat by its predecessor. However, by the end of the decade, it had gained a dedicated following, allowing it to stand side-by-side with Ocarina of Time as one of the greatest games ever made. Does Majora’s Mask successfully answer the question of what kind of game could possibly follow a work as universally beloved as Ocarina of Time?

Starting the GameWARNING: Due to the nature of this work, there will be unmarked spoilers throughout this review for both Ocarina of Time and Majora’s Mask.

Once upon a time in the Kingdom of Hyrule, a man named Ganondorf seized control of the throne. He ruled the land with an iron fist until a youth named Link appeared. With the aid of his companions, he was able to overthrow the tyrant, restoring peace to a land that had not known it for seven long years. At the end of a fierce battle, Princess Zelda sent him back seven years so he may relive the childhood he lost. Upon arriving in the past, Link’s companion, Navi, bid him farewell, disappearing into a ray of sunlight. Sometime after warning the Zelda from this new era of Ganondorf’s evil intentions, he set out on a journey to find Navi.

While traveling through the Lost Woods with his horse, Epona, he is accosted by a strange, masked imp known as the Skull Kid and his two friends, fairies named Tatl and Tael. As he is dazed, the Skull Kid steals his ocarina, a keepsake from the princess. When Link comes to, the Skull Kid mounts Epona and takes off into the deepest section of the woods. Link hangs onto the Skull Kid’s leg for a while, but is eventually thrown off. He pursues the three of them on foot through a portal in a large, hollow tree. The path abruptly stops, and he is unable to prevent himself from falling into a deep chasm.

Miraculously, he survives the fall. Looking up, he notices the Skull Kid, who claims he got rid of Epona. He then uses the evil power of the mask to turn Link into a Deku Scrub. As the Skull Kid makes his exit, Tatl and Tael are separated from each other. Tatl immediately blames Link for her predicament, though also realizes she has no choice but to ask for his help to have any chance of being reunited with her comrades.

In the brief time you control Link before a curse is placed on him, you’re presented with an interface similar to that of Ocarina of Time. The “B” button is the designated sword button while the “A” button’s function changes depending on context. Which action the latter preforms when pressed, if any, will be written on its graphic. By pressing the “R” button, Link will raise his shield, protecting him from most enemy attacks. When you obtain inventory items later, you can assign them to the left, bottom, and right “C” buttons. Once again, the biggest advantage this interface has compared to any 2D installment thus far is that it significantly reduces the number of times you must pause the game. In fact, accessing the menu for the first time reveals one improvement over Ocarina of Time right off the bat. The menu takes much less time to load and scroll through; once you’ve played for long enough, it becomes an unconscious action.

Majora’s Mask wastes no time defying the audience’s expectations. You’re only in control of Link for a few minutes before a curse is placed upon him. That is to say, the game is requiring you to unlock his default form. What makes this development particularly interesting is that the species he has been transformed into existed almost exclusively as monsters meant to hinder your progress in the previous entry.

In this new form, he has the ability to burrow under large flowers and launch into the air. From here, he uses two smaller flowers to glide for a short length of time. These flowers come in two colors: pink and gold. Golden flowers allow Link to fly further and for a greater amount of time than the pink ones. One important thing to keep in mind is that the flowers only exhaust energy when the control stick is tilted. If you’re just descending, you can hold onto the flowers until you touch the ground or begin actively moving again.

On a similar note, when Tatl decides to help Link, you’ll learn that she functions identically to Navi. Her presence is fundamental for a vital mechanic called “Z” targeting. Holding down the “Z” button normally turns the camera in the direction Link is facing, indicated by two letterboxes adorning the top and bottom screen. He can still move in this state, though tilting left and right on the control stick will cause Link to strafe. Meanwhile, tilting the stick towards you causes him to back up while facing forward. Based on context, Tatl will fly towards certain set pieces. She will turn yellow, blue, and green depending on whether there is an enemy, NPC, or miscellaneous point of interest nearby respectively. When she is in this state, you can hold down the “Z” button so Link may focus on the object. If she has additional information about it, you can press the top “C” button to hear her out.

After navigating the subterranean cave system, Link and Tatl emerge inside a clock tower whereupon they are greeted by the mysterious Happy Mask Salesman. He claims he has the power to restore Link’s true form, but first, he must retrieve both the Ocarina of Time and the Skull Kid’s mask. There is a caveat to this agreement; the salesman’s busy schedule means that he must leave the land in three days. Despite the small amount of time he has to complete his task, he is confident Link will prove successful in taking back the stolen items, sensing his courage.

Stepping through the nearby doorway takes Link and Tatl to Clock Town, the geographic and economic center of this land called Termina. As was the case in Ocarina of Time, time moves at a much faster rate than it does in the real world. Unlike in Ocarina of Time, however, it flows regardless of your current location; being indoors or exploring a town will not stop the clock. The exceptions to this rule are far and few in between, though you don’t have to worry about taking too much time reading NPC dialogue because talking remains a free action. Even then, it doesn’t give you much room for error, as each hour translates to twenty-seven seconds in real time, meaning you have roughly half of an hour to accomplish all your goals.

One of the first things you wind up doing in the game is speaking with a magical being known as the Great Fairy. In exchange for restoring her power, she grants Link the ability to use magic, which is measured as a green bar below the health meter. It functions simply enough; some items and techniques require magic power to use. If you run out, you naturally can’t use any of them. Being conferred magic allows Link in his new form to shoot bubbles from his snout. When you press the “B” button, the game switches to a first-person perspective from which you take aim and fire. Alternatively, if you’re “Z” targeting, you can stay focused on your target and fire from a third-person perspective. This principle will apply to any weapon that normally forces a first-person perspective.

I feel one would be hard-pressed to find a more effective introduction to a video game than the one for Majora’s Mask. This is because it allows you to grasp the story’s central conflict on your own before laying all the cards on the table. You discover that the Skull Kid is on top of the Clock Tower using an observatory’s telescope. Once you find him, the telescope points to the sky, and it is then you’ll notice something is very wrong with this land.

The realm’s moon has left its orbit and is looming ominously on the horizon. Though it’s entirely possible to make it to this point without looking at the sky, gazing through the telescope ensures you can’t miss it. It is at that point you realize the three-day time limit imposed upon you doesn’t just signify when the salesman is to take his leave; it’s counting down the world’s final hours. If you had any lingering doubt, the numerous earthquakes that permeate throughout the final day will erase it completely.

Upon confronting the Skull Kid, Link manages to take back his ocarina. Zelda gave it to him as a memento of the short time they spent together, and before he left on his journey, she reminded him of the Song of Time. As the notes of the song echo out to the fiery sky, the world disappears from view. He and Tatl then emerge from the Clock Tower once more. Looking up at the sky and noticing its normal blue hue and the moon having been sent back, they realize they’ve returned to the first day they arrived in Termina.

With the Ocarina of Time in tow, Link returns to the Happy Mask Salesman, who in turn teaches him a song that restores his human form. The curse is then sealed inside a mask, which allows Link to assume the form again upon wearing it with the added bonus of being able to return to his normal self at will. The celebration is cut short when the salesman realizes Link failed to retrieve the imp’s mask. It is here that both Link and Tatl learn of its true nature. Called Majora’s Mask, the artifact was created by a long-extinct tribe for use in hexing rituals. Soon, it became clear the mask’s power could lead to calamity if it ever fell into the wrong hands, so the tribespeople sealed it away before anyone had the chance. The salesman went to great lengths to obtain the mask for himself, but the Skull Kid had ambushed him as well. Due to the mask’s influence, the Skull Kid’s antics turned from harmless pranks to truly malevolent acts, and now he wishes to bring about the end of the world. Despite the grim situation, the salesman is relieved when Link agrees to retrieve the mask, having faith that he will complete his mission.

When they emerge from the tower, Tatl recalls her brother’s words as they were confronting the Skull Kid. “Swamp. Mountain. Ocean. Canyon. Hurry… The four who are there… Bring them here…” Realizing this corresponded to the regions lying in the four cardinal directions from Clock Town, she advises Link to head south to the Woodfall region. Though unsure of what their journey will entail, they venture forth, determined to give Termina a future.

Delving into the ExperienceAs learned from the trials and tribulations you went through to retrieve the Ocarina of Time, Majora’s Mask revolves around a gimmick involving you reliving the same three days as you journey through Termina. Thankfully, time doesn’t flow as quickly on subsequent cycles; an in-game hour is around forty-five seconds long with three days translating to fifty-four minutes in total. Furthermore, by playing the Song of Time backwards, the entire cycle lasts a more generous three hours with each hour taking two-and-a-half minutes. It is through this development that certain critics and fans have drawn comparisons to the classic 1993 comedy Groundhog Day wherein the protagonist depicted by Bill Murray inexplicably relived the eponymous holiday repeatedly against his will. Majora’s Mask differentiates itself in that the time loop is both voluntarily induced and exploited by the player to achieve their goals.

Indeed, not only does retuning to the dawn of the first day prevent the world from facing certain doom, it’s how you save the game. Admittedly, it is something of an annoying limitation at first. It was especially bad in the Japanese version, as it was the only way one could save. Luckily, when Majora’s Mask was being localized, the designers added a feature that makes it far more manageable. Scattered throughout Termina are owl statues that spread their wings when struck with Link’s sword. Examining the statue after it has been activated allows the player to suspend the game. The temporary save is then erased once a new session begins. As a trade-off, Western versions of the game only have two save slots to the original’s three. If you’re the only one who uses the cartridge, you can take advantage of the copy feature on the file select screen, as it duplicates the temporary save as well. This is useful if you’re fulfilling a task that only gives you one attempt per cycle.

In both versions, going back in time causes you to lose all of your money and ammunition. This is manageable because in West Clock Town, there is a bank in which you can store your money. Somehow, it’s immune to effects of time travel, though amusingly, it’s implied Link is withdrawing other peoples’ money owing to the fact that the teller stamps customers with a special ink which displays their name and current balance. Ammunition is simple enough to find when enemies drop them or by cutting plants, so starting every cycle with zero is rarely an issue.

Those returning from Ocarina of Time may be questioning why there is no mini-map in the bottom-right corner of the screen. Make no mistake, the feature does make a return, but it won’t appear until you purchase a physical map from an eccentric man named Tingle. You can get his attention by shooting down the balloon he uses to float around. He can be found in every region of Termina, offering a different set of maps in each one. He offers a cheap map for the current region and a more expensive one for your next destination.

In Ocarina of Time, the Happy Mask Salesman was the proprietor of a shop in Hyrule Castle Town. Visiting it led to a sidequest wherein you borrowed masks from the shop in an attempt to sell them to various NPCs. Once you found a customer, they would offer to buy the mask from you. In turn you would pay the salesman money equal to the mask’s base value. Doing so would unlock a new mask for you to sell. By selling enough of them, you would gain the Mask of Truth, which allowed you to listen to Gossip Stones. For the most part, the stones dispensed information that wasn’t required to complete the game, making the mask more of a novelty than anything else. Still, it added to the experience, giving a fair amount of characterization to certain NPCs, and what the stones’ messages helped build a world by providing story fragments.

For this installment, the Happy Mask Salesman has a pivotal role, and fittingly enough, so do the masks themselves. You’re no longer limited to carrying one at a time; in fact, there’s a second inventory screen dedicated to housing them all. After equipping one, you press the corresponding “C” button to equip it and once more to put it away. The Deku Mask is the first one you’re given, and in a rather creative twist, the game showcases its functionality before rewarding it to you. It is one of the three masks that allow Link to shapeshift into an entirely different species. A majority of the remaining masks are more mundane, either having a single purpose fulfilling certain sidequests or granting Link a passive advantage when equipped such as the ability to run at a faster speed. NPCs may give unique reactions to certain masks or forms, so it helps to experiment and see what they have to say.

One common thread the dungeons in Ocarina of Time shared with ones from A Link to the Past was that they were introduced to you in tiers. That is, you were made to journey through Hyrule in search of three important artifacts with which to advance the plot. In A Link to the Past especially, it would be easy for a player to believe that the quest to find the three items constituted the entire experience. Both games operated on this premise before revealing that your journey was only just getting started. A Link to the Past underscored this by labelling the sixth dungeon “Level 1” while Ocarina of Time let you know it was no longer pulling its punches as it proceeded to skip forward seven years.

Taking note that you’re only told from the onset to investigate four regions and complete their respective dungeons, a savvy player might deduce there is more to the game awaiting those who make it through them. This time around, such a supposition would be false; a second set of dungeons does not exist. This is understandably a point of contention among fans. With talented people behind their creation, one advantage the franchise had over its contemporaries was that only a scant few teams could rival them when it came to dungeon design. Though Ocarina of Time may not have boasted the same, impressive number of dungeons A Link to the Past possessed, the team compensated for this deficiency by seamlessly incorporating them into the setting while also making them far more involved. Having a mere four dungeons sounds like a deal-breaker, but I can assure you the smaller Majora’s Mask team was also able to overcome this disadvantage.

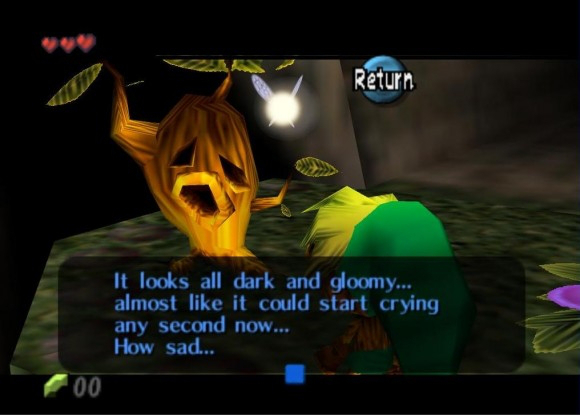

To begin with, the getting to a dungeon in this game is a matter of truly immersing yourself in the region. As you explore and interact with the locals, you learn of their culture, history, and current plight. Ocarina of Time had shades of this as well, but Majora’s Mask goes further with the concept. Even if the citizens aren’t always hospitable to outsiders, you begin to sympathize with their plight, and it’s only through learning an important song of theirs that you can access these dungeons. Actually getting there usually involves going through areas that could be considered mini-dungeons in of themselves. In the older entries, the first level was often presented you before you even knew the overarching plot; Majora’s Mask makes you earn the privilege of reaching the entrance.

However, I and most fans of this game would argue the biggest draw lies not in the dungeons or the paths you take to reach them, but the abundance of sidequests. Ocarina of Time had thirty-six Heart Pieces scattered throughout Hyrule. In the land of Termina, there are fifty-two Heart Pieces to find. Coupled with the twenty-four masks awaiting astute players, it is from there one might grasp just how many sidequests would be necessary have all of these items offered as rewards.

The sheer volume of sidequests by itself is impressive, but their true value is how much personality they confer onto the various characters that inhabit the world. Hyrule had no shortage of colorful NPCs, but many of them barely had any purpose beyond providing interesting dialogue. In Majora’s Mask, a large number of NPCs have names and extensive schedules that change depending on the day. Because of this, Majora’s Mask could be said to not have a single narrative, but rather multiple ones that happen to share the same universe. Many of these people have aspirations, desires, and backstories that give them an identity beyond being an NPC who holds an important item they will reward them with if you do them a favor. To an even greater extent than Ocarina of Time, the writers succeeded in breathing life into these characters.

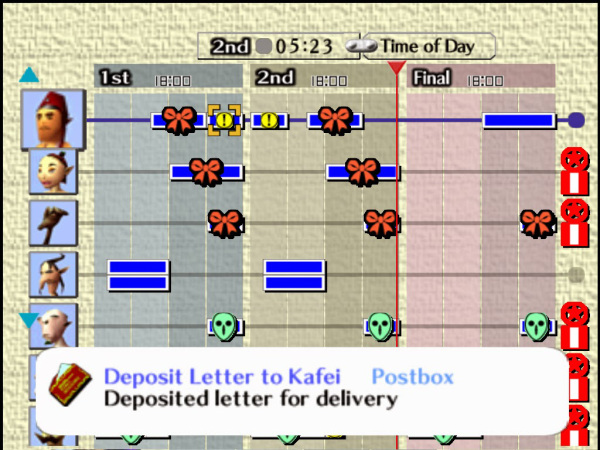

A particularly troubled citizen will be documented in your personal notebook, which can be obtained by the children you spoke with during the first cycle. From there, they gain a portrait, and blue lines appear to the right of them. These lines indicate the times in which important events associated with that character occur. As the above screenshot indicates, you can deposit a letter into the mailbox so the postman can deliver it to its intended recipient. This must be done from midnight to 6:00am on the first day or 6:00am to noon on the second day.

What makes these sidequests intriguing is how, in another parallel to Groundhog Day, you wind up studying these character’s routines extensively in order to succeed in helping them. In fact, many of these quests have divergent paths. In one scenario, you are given an important letter intended to be sent to the writer’s mother. You can either hand deliver it personally or turn it over to the postman, and you get different rewards depending on your course of action. In a normal game, a similar situation would force you to make a decision capable of drastically altering the rest of your playthrough. In Majora’s Mask, with the ability to reset the cycle via time travel, you can go down both routes without having to restart the game.

By this point, it should be made abundantly clear that Majora’s Mask is far from an ordinary game – even by the standards of a series which regularly changes things up. These oddities not only present themselves as you play, but also the more you read into the narrative’s subtext. The creators did a splendid job building a virtual community. It makes it all the more tragic that their days are numbered.

WARNING: This section will contain unmarked spoilers for the game’s ending.

Majora’s Mask begins innocently enough before blindsiding you with a premise far bleaker than anything the series had to offer by this point. Much of this radical shift can be attributed to the experiences the development staff had gone through to complete this game. In addition to the strict deadline taking its toll on certain members, one harrowing incident left an impact on them that influenced the tone of their work. It happened when the team took a trip to South Korea in order to attend a member’s wedding. It turned out to be unfortunately timed, for North Korea was initiating Taepodong-1, a three-stage technology demonstrator with the goal of developing intermediate-range ballistic missiles. Mr. Aonuma recalled the event in an interview several years after the release of Majora’s Mask. One conversation in particular with Mr. Koizumi and the other members stuck out in his mind.

“Come to think of it, it’s somewhat strange to come to a wedding in a situation when missiles may fall down today.”

The moon looms over the horizon of an unsuspecting, disbelieving Termina, threatening to bring everything to an end much like how those missiles had a very real possibility of raining down from the sky the day they attended that wedding. This even influenced the development of a famous sidequest with the goal of reuniting a pair of lovers moments before the moon crashes.

Shigeru Miyamoto and Yoshiaki Koizumi came up with the plot that became the basis for Mitsuhiro Takano’s script. Mr. Koizumi’s influence is especially evident, as Majora’s Mask hits many of the same story beats as Link’s Awakening. The most obvious link is that neither game takes place in Hyrule. Though many Terminans look identical to Hylians, it resides on another plane of existence. That the people of this realm invented devices capable of taking photographs while also having plans to build prototype rockets suggests they are more technologically advanced than Hylians.

Furthermore, though they look identical, they often have wildly different personalities or occupations from their Hylian counterparts. While exploring the swamp, you meet two witches named Koume and Kotake. These characters appeared in Ocarina of Time, but their role was completely different. Not only were they fought in a boss encounter late in the game, they had an important connection to the main antagonist. Here, they’re the owners of a potion shop, and helping them is an important step towards accessing the first dungeon. There are more subtle cases like this that run throughout the game. If you replay Ocarina of Time after clearing this one, don’t be surprised if you begin noticing otherwise unremarkable NPCs wandering the streets and thinking of their Terminan doppelgängers.

One of the most noticeable antitheses to result from this lies in the fairy who accompanies Link on his journey. With her sharp tongue and aloof nature, Tatl is a foil to the formal, straightforward Navi. Though some may find her unwillingness to divulge information on enemies introduced in Ocarina of Time irritating, I appreciate the concept behind her character because it allowed the writers to go in a direction they couldn’t with Navi. She begins the game openly antagonizing Link. After she gets separated from the Skull Kid and Tatl, she only helps Link as a means to be reunited with her brother. When she witnesses the Skull Kid’s intent to destroy the world firsthand, she realizes just how much the mask has warped his being. As she and Link explore Termina and are confronted with evidence of the Skull Kid’s destruction, she becomes more determined to free the guardians and save the world – even if their mission culminates in the loss of her former friend.

Perhaps the greatest source of irony this game has to offer is that while you may see several familiar faces, they only serve to underscore the land’s alien nature. In Ocarina of Time, Link was the one chosen by the Master Sword to defeat Ganondorf and restore peace to Hyrule. This task involved awakening seven sages and using their collective power to seal the tyrant in the sacred realm. Absolutely none of that applies in this setting. Link’s status as the Hero of Time doesn’t matter in the face of an impending apocalypse in a realm that’s not his own. This situation succeeds in lending a fair bit of characterization to him. He isn’t out to save Termina at the behest of an ancient prophecy, but rather because he is a true hero who has grown considerably since his last adventure. This is exhibited while playing the game as well when you realize he can utilize any of the weapons only his adult self could use.

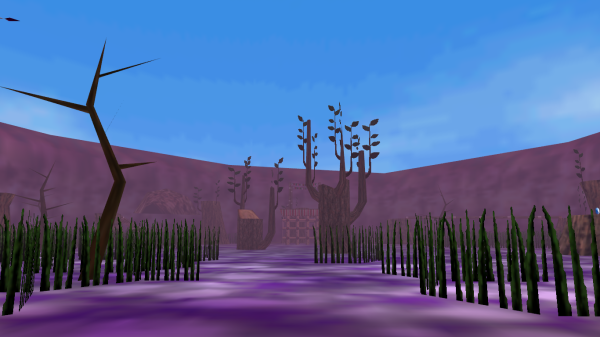

When you arrive in the Woodfall region, you will discover that the swamp has been poisoned. By completing the Woodfall Temple and defeating the monster that resides there, you end up freeing one of Termina’s guardian deities.

It is here that you learn what you need to do to prevent Termina’s destruction and the nature of the four beings of whom Tael spoke. Upon returning to Woodfall, the poisoned water purifies itself. Seeing the region restored to normal carries a feeling of satisfaction saving the world normally entail, yet uncharacteristically for this series, the deed feels empty. This is because saving the game erases the goodwill from this act. The guardian remains free as you travel back in time, and possessing the monster’s remains allows you to refight it immediately upon entering the dungeon. Even so, no matter how many times you fight the demon, it will revive again and again whenever you reset the cycle.

One esoteric theme that runs throughout the game is the number four. To wit, there are four major regions each with its own temple, four guardians you must free, and four main forms Link can assume throughout the game. This arc number serves as a mask of sorts for the game’s true face. In Japanese, the word for this number, shi, is a homophone for death when using the kanji’s on-reading (an approximation to its Chinese pronunciation when the character was originally introduced). As such, it’s considered bad form to mention the number four around ill family members or festive holidays, and certain structures such as hospitals or residential apartment buildings will elect not to list any floor with the digit, skipping from three to five. It’s to the point where the word’s alternate pronunciation, yon, is used in situations when corresponding readings for other numbers wouldn’t. This connotation is also present in other East Asian countries such as China and Korea, being far more pervasive than triskaidekaphobia, the Western equivalent.

Accented by the clock adorning the bottom of the screen constantly ticking down to the apocalypse, death comes in many forms throughout this adventure. Though it’s not overly obvious in the Woodfall region, in your next stop, Snowhead, you come across the wandering spirit of the Goron hero, Darmani. By playing the Song of Healing for him, you gain the second transformation mask, allowing you to assume the form of a Goron, a strong, mountain-dwelling species. In fact, when you use it, you’ll notice that Link bears more than a passing resemblance to Darmani himself, and his fellow Gorons believe he has come back from the dead when spoken to. It adds a layer of tragedy to the proceedings, as Darmani’s spirit helps you save his people and cement his status as a hero from beyond the grave, but the dramatic irony is known only to Link, Tatl, and the player.

The third region, the Great Bay, sets up a distinct scenario with a similar presence. The twist is that you encounter the fallen hero shortly after he’s been mortally wounded. This time, it’s a Zora guitarist named Mikau. Once again, by playing the Song of Healing, his body disappears, leaving behind the Zora Mask. As a member of the aquatic race, Link has far more mobility in large bodies of water when wearing the Zora Mask. If anything, this is setting itself up for a markedly more sorrowful situation, as Mikau’s friends are unaware of his true fate.

This running theme hits a pinnacle in the form of the final region, the Ikana Canyon. Though you don’t receive any new transformation masks during your travels here, it features more references to dead spirits than in any other point of the game. Fittingly, it functions as a final exam of sorts, requiring you to switch between the four forms Link can assume by this point. The song you need to access the dungeon is call the Elegy of Emptiness, and the effigies left behind from playing it serve as a stern, poignant reminder.

These spirits continue to linger in this world, and it’s by accepting the reality of death that you’re able to see your quest through to the end.

After all of this, it would appear that the Woodfall region is the exception to the rule, and the Deku Mask was obtained from a curse placed on Link rather than a dead spirit. However, if you partake in a sidequest involving a member of the Deku King’s butler, he mentions that Link reminds him of his son. It’s heavily implied in the ending sequences that the tree you passed exploring the underground catacombs at the beginning of the game is the dead body of his son. The Skull Kid’s curse didn’t manifest ex nihilo; he infused Link with the spirit of the butler’s son. The game’s introduction foreshadowed its tone long before you had any idea of the darkness lying just beneath the surface. Fittingly, it’s in a manner that ties the ending into the introduction – not unlike what you do whenever you play the Song of Time.

Drawing a ConclusionPros:

|

Cons:

|

Shortly after the series successfully made the leap from 2D to 3D, fans began to debate over which game could be considered the pinnacle. With the many paths the series took leading up this installment and would take in the coming years, christening any of them as the best of the best is a daunting task indeed. When discussing certain other series, it can be easy to make a strong case for one entry reigning supreme over all the others whether it was because one clearly had more effort behind its creation or it managed to powerfully resonate with the audience. Generally, I find it’s easier whenever a series tends to hit the same notes with each installment because at that point, it becomes a matter of determining which one is the best using the rigid standards the artists themselves laid out. This is why when it comes to The Legend of Zelda, there will probably never be a definitive consensus; every installment, though molded from a loose outline, experiments with new ideas and mechanics to the extent where no two installments can be said to share the exact same identity. Regardless of what the case may be, I firmly believe Majora’s Mask is the absolute best game in the series.

Nintendo’s solution to following up a game as momentous as Ocarina of Time was to do the impossible by coming up with something even better. Born from daydreams and nightmares, Majora’s Mask is truly an otherworldly experience no work in any medium before or since has, or arguably could, offer. From feeling the pressures of meeting a strict deadline to a worrying about a possible military attack, this game is a product shaped by the circumstances surrounding it. Had any part of its production been different, it’s entirely possible it wouldn’t exist in its current form. Much like Ocarina of Time, what the staff went through to complete this project formed a secondary legend to supplement the one presented within the confines of their fictional universe. Yoshiaki Koizumi’s efforts writing the scenario Link’s Awakening proved he had an incredible potential for storytelling, and Majora’s Mask is when it fully blossomed. Similarly, it becomes hard to believe that when he first joined Nintendo, Eiji Aonuma had never played a video game in his life. After this installment, he cemented himself as one of the greatest designers in the business, showcasing an admirable amount of personal growth.

There was one major problem that would plague many AAA releases in the next two decades. It involved writers conceiving worlds without even the tiniest veneer of hope for the world or any of its inhabitants. This was mostly born out of a misguided desire to accelerate the medium’s growth and get outsiders to acknowledge its cultural legitimacy. More often than not, it traded one form of immaturity for another. In many of those cases, I feel their problems could have been avoided had they truly studied Majora’s Mask. The way it treats its dark plot is somewhat analogous to the ancient Greek myth of Pandora’s Box. Though all the evils of the world were unleashed upon opening the box, a tiny shred of hope remained inside. Majora’s Mask remembered to give hope to the players as they wandered the land of Termina, and in doing so, demonstrated a level of maturity many later games with a dark tone lacked.

On a more basic level, Majora’s Mask is the perfect sequel to Ocarina of Time, using its previous canon as a vehicle to explore uncharted territory. If you’ve finished Ocarina of Time, do whatever you can to try this game out as well. Whether it’s the original Nintendo 64 version or the 3DS remake, you cannot be led astray. In fact, unlike many 3D games from the same era, Majora’s Mask has only gotten better with age. All I can say is that if you have never played it before, I guarantee you’re in for an unforgettable experience.

Final Score: 10/10

Advertisements Share this: