“Like most children before the age of TV and computer games, I loved being outside,” writes Jane Goodall in her book Reason to Hope: A Spiritual Journey, “I loved playing outside, playing in the secret places in the garden, learning about nature. My love of living things was encouraged, so that from the very beginning I was able to develop a sense of wonder, of awe, that can lead to spiritual awareness.”

When I read that passage by Goodall, I instantly connected with her and her experience. While I had TV, I spent more time in books and the woods. Both were ways of exploration and self-discovery for me. Both libraries and nature were places of freedom, self-education, self-discovery and deep connection to the realization that I’m not alone. When I look at my past, I see how literature and language and the natural world were all interconnected for me.

My mother encouraged both my love of reading and my love of nature. And I’m sure she was thrilled to go through my pants’ pockets before she washed my clothes: never knowing what she might find in them (small stones, bird bones or feathers, a snake skin, a brightly colored leaf).

It was my discovery of the wonders of nature, like Goodall’s, that opened me to a sense of awe that undergirded a spiritual awareness that was deeper and richer than that I experience in church as a child. It’s also why, as a parent, I ensure that my own sons spend time in nature, to get that sense of the amazing delight and reverence for trees and plants and animals and streams. To be connected and rooted to the natural world and not just to the technological one.

Later in her book, Jane Goodall writes about how she was “not at all keen on going to school.” These are words that harken to my own ambivalence and dislike of systemized education that feels more like chores and prison than opportunities for discovery or creativity or even inspiring critical thinking. My room was filled with books. We took weekly trips to the local library. I would check out stacks of books and then spend time losing myself within their words and worlds, just as I did within the woods.

Many of the books I loved as a boy were either about far off imaginary places, magical places, or wild and wooded places. Fairy tales were a start, but then they were followed by books like The Wind in the Willows, The Secret Garden, Doctor Doolittle, Charlotte’s Web, Winnie the Pooh and The Jungle Book.

I can still recall reading The Wind in the Willows, one of my most cherished and beloved books, and becoming enthralled with the passage where Kenneth Grahame writes, “All this he saw, for one moment breathless and intense, vivid on the morning sky; and still, as he looked, he lived; and still, as he lived, he wondered.” That was me he was describing. I could and, still can, get lost into staring at the sky. I have a fascination with skies and clouds that is unexplainable and I love that it is. I delight in mystery and the inexplicable and unexplainable.

Needless to say, I relished that Jane Goodall also loved The Wind in the Willows. As she writes, “…to this day, I remember the beautiful and mystical experience shared by Ratty and Mole when they found the missing otter cub curled up between the cloved hoofs of the sylvan god, Pan.”

I, too, remember that moment. Certainly this Pan was a kindlier and gentler, more English version of Pan than that of classical Greek. Grahame’s Pan owed more to Wordsworth as a protector of the English wild countryside. Pan symbolizes nature itself and we see the awe and reverence he inspires in the dialogue between Ratty and Mole:

I, too, remember that moment. Certainly this Pan was a kindlier and gentler, more English version of Pan than that of classical Greek. Grahame’s Pan owed more to Wordsworth as a protector of the English wild countryside. Pan symbolizes nature itself and we see the awe and reverence he inspires in the dialogue between Ratty and Mole:

“Rat!” he found breath to whisper, shaking. “Are you afraid?”

“Afraid?” murmured the Rat, his eyes shining with unutterable love. “Afraid! Of Him? O, never, never! And yet—and yet—O, Mole, I am afraid!”

Then the two animals, crouching to the earth, bowed their heads and did worship.

This was a reverence for wild, untamed places. This was a respect and wonder for the natural world. It was what I felt every time I ventured into the woods behind our house, for when I saw a fox, or discovered raccoon tracks, or spotted a barred owl on a tree branch overhead.

As a boy, I climbed trees. Loved climbing trees. To hide out. To read. To be alone. To think.So when I read Italo Calvino’s The Baron in the Trees, I understood, at once, why the protagonist, Cosimo, climbs a tree on his father’s estate and vows never to set foot on the ground again. There was nothing like being near the top of a tall tree when the wind began to move it, the tree began to sway. Overhead the pale clouds glided by in the summer sky.

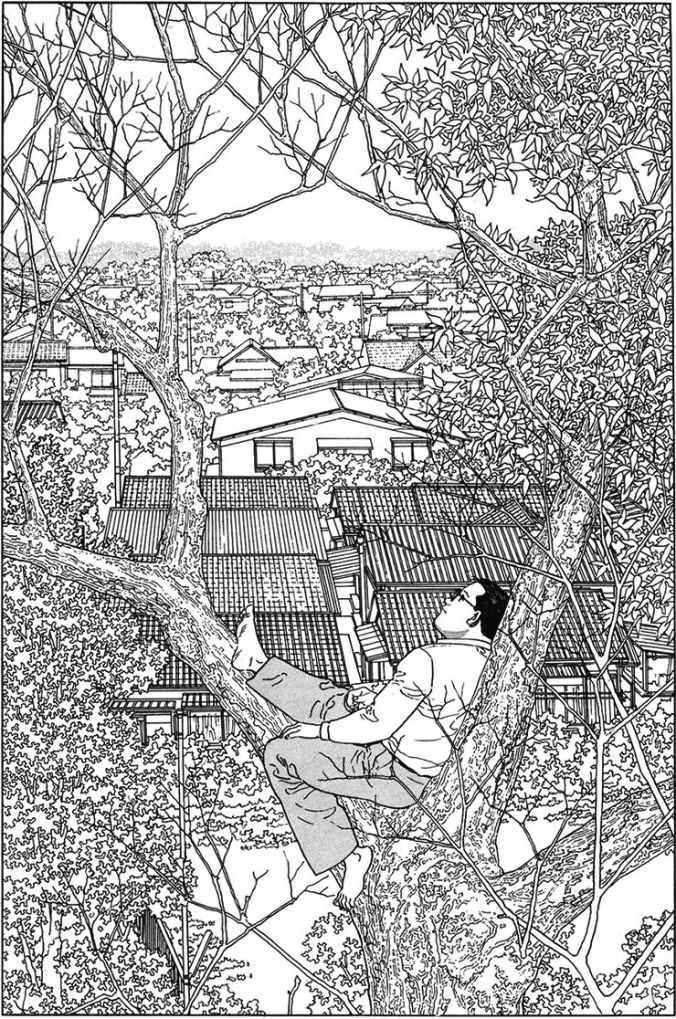

It’s also one of the many reasons why I connected with Jiro Taniguchi’s beautiful and simple graphic novel The Walking Man. It is a lovely reflective and meditative work on a man walking. The narrative shows what he encounters on each walk: the people, places, and nature. One of my favorite images is of him, resting in the crook of a tree, gazing out over the rooftops of houses in a suburban Japanese neighborhood.

This manga wonderfully illustrates the Japanese art form called “Ukiyo-e.” The philosophy behind Ukiyo-e is of living in the moment, of appreciating life’s simple pleasures and the beauty inherent in nature. This work by Taniguchi causes anyone who takes the time to spend within its pages towards contemplation, reflection and awareness. It takes us out of the pace of our busy, hectic world into one of Ukio-e.

When I first discovered The Walking Man, I could easily identify with its protagonist. There is a peace to his world that I find in my own walks, in my own interactions with nature. I can remember, as a boy, how I loved walking through the tall, woodland grass that brushed against my skin as I passed through the field to enter the woods.

Whenever the world has felt chaotic, I turn to the woods and to the words of writers like Mary Oliver, Jane Goodall, Henry David Thoreau, Robert Macfarlane, John Muir, William Wordsworth, Annie Dilllard, W.H. Hudson, W.S. Merwin, Loren Eiseley, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Robin Wall Kimmerer, Rebecca Solnit, Wendell Berry, or Gary Snyder. They draw me back from the hopelessness one so often sees in the media, to the reality of the natural world where there is true connection and where one can find peace and hopefulness.

“There is no mystery in this association of woods,” writes Robert Macfarlane in The Wild Places,”and otherworlds, for as anyone who has walked the woods knows, they are places of correspondence, of call and answer. Visual affinities of color, relief and texture abound. A fallen branch echoes the deltoid form of a streambed into which it has come to rest. Chrome yellow autumn elm leaves find their color rhyme in the eye-ring of the blackbird. Different aspects of the forest link unexpectedly with each other, and so it is that within the stories, different times and worlds can be joined.”

The woods and forests are an enchanted, magical world because I came to them as a boy and through books. I saw through the lens of the excitement that one never knew what one would discover or encounter in both the natural world and in the pages of books. Both opened me up and have helped me get through the hardest times of my life (How often did I feel the nourishment and healing of the woods when I took walks there after the death of my mother?).

As the world around me appears to me in chaotic disarray and confusion, I am returning again and again and again to the peace of wildness, of finding the beauty and grace in leaves that are turning glorious golds and reds and oranges all about me. Of putting my hand into the chilly creek to remind myself: This is life.

Advertisements Share this: