In his book The Irresistible Fairy Tale: The Cultural and Social History of a Genre, Jack Zipes wrote, “Fairy tales begin with conflict because we all begin our lives with conflict. We are all misfit for the world, and somehow we must fit in, fit in with other people, and thus we must invent or find the means through communication to satisfy as well as resolve conflicting desires and instincts.” The truth of his words sink deeply in as I have begun to write my own fairy tale after having read and collected them for so many years.

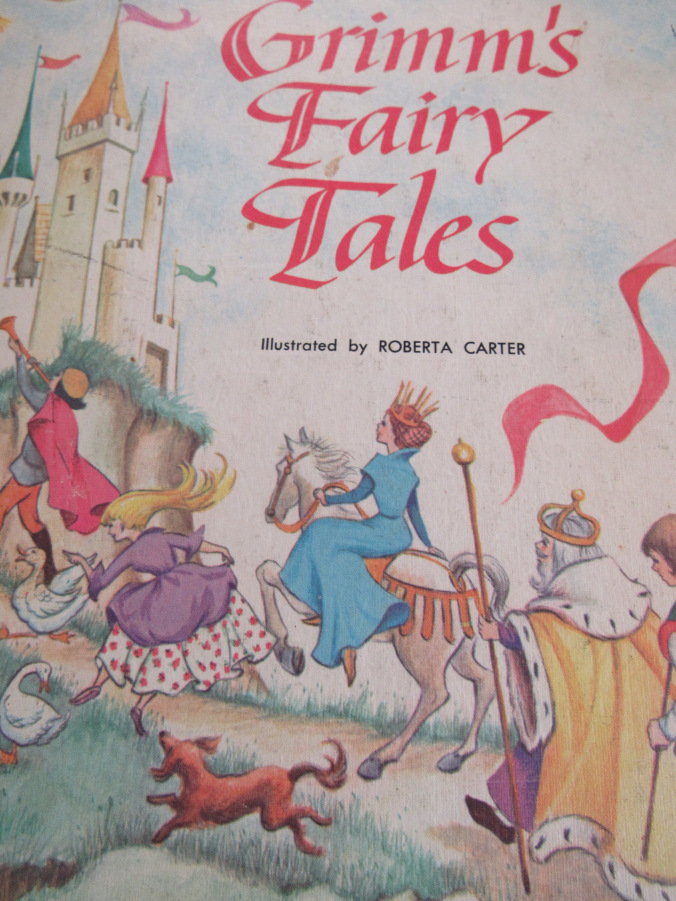

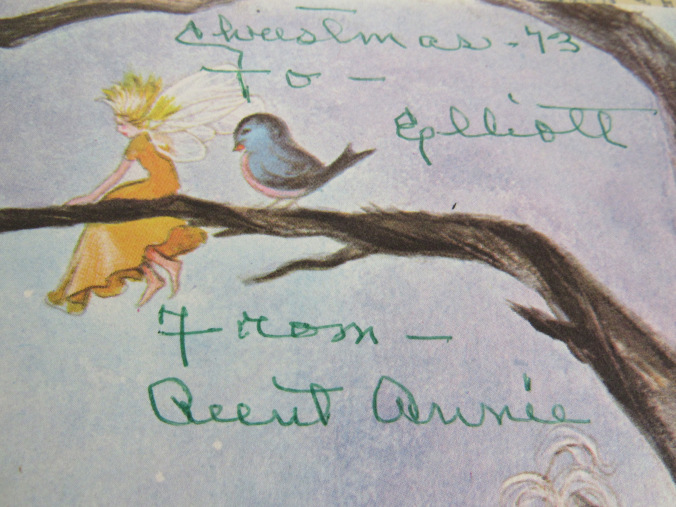

I was first introduced to the genre when my Great-Aunt Annie gave me a small picture book of Grimm’s Fairy Tales (much of the darkness and brutality of their tales were cleaned up in this edition). It was one of the first books given to me as a Christmas present and would become one of my childhood favorites.

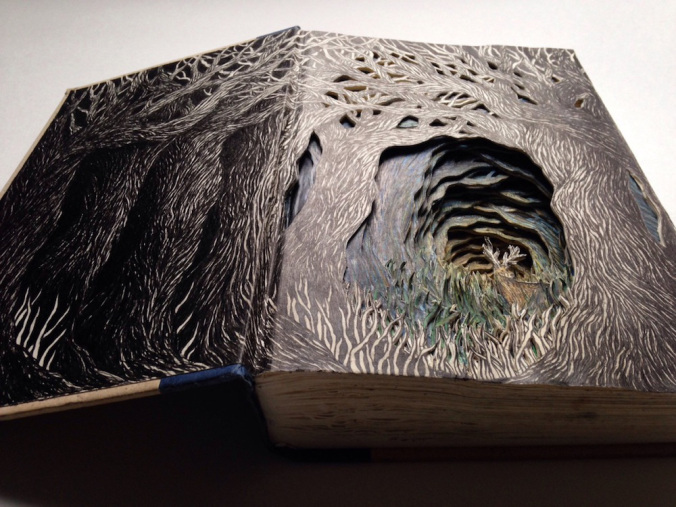

This collection of fairy tales is one of the books I have kept over the years because I cannot imagine my life had I not been given it. I did not just read fairy tales, but became a part of them and they of me. There was something deep and truthful about their stories that enraptured me and engrossed me and drew me in. I entered fairy tales the way children in them so often entered the forest. The places they led me to were frightening and fantastic and allowed me to dream of magic.

In our home, the conflict that so often arose there, could also be mirrored in the relationships of fairy tales. Families were often fractured and broken. And yet, no matter how difficult and dangerous the situations were, these stories always ended with a happily ever after, with overcoming the terrors and the troubles and the trials. As a quiet, shy and introverted boy. I wanted to believe in such endings.

And yet, despite my love of fairy tales, I had never really attempted to write one until the beginning of this summer. It started as a project between my younger son and myself. Since he is adopted and often struggles with identity, I thought what could be a better way for him to do just that than in a genre that is all about identity and struggling with who one is and of the monsters and forces in the world around us. What better gift than to work on a story where such struggles end in triumph?

He was thrilled when I proposed the idea to him. But what would our story be about?

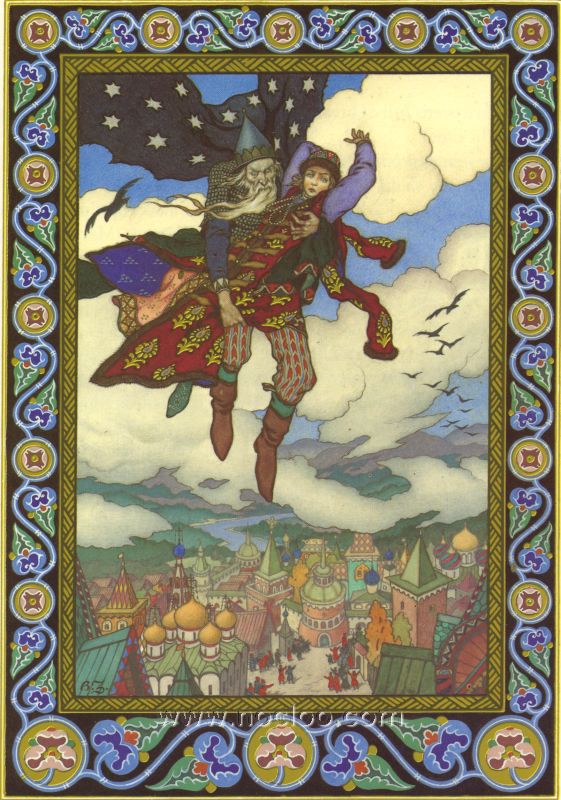

It was my son who came up with what our fairy tale would be about: a young boy who loves with his parents by the edge of a great forest learns that he was a foundling that they discovered on a bed of moss in the forest itself. Desiring to know his true identity and where he came from, the boy decides to journey into the forest to find the answers to his questions.

The poet W. H. Auden once said, “The way to read a fairy tale is to throw yourself in.” It’s also what you must do to write one as well. So we did!

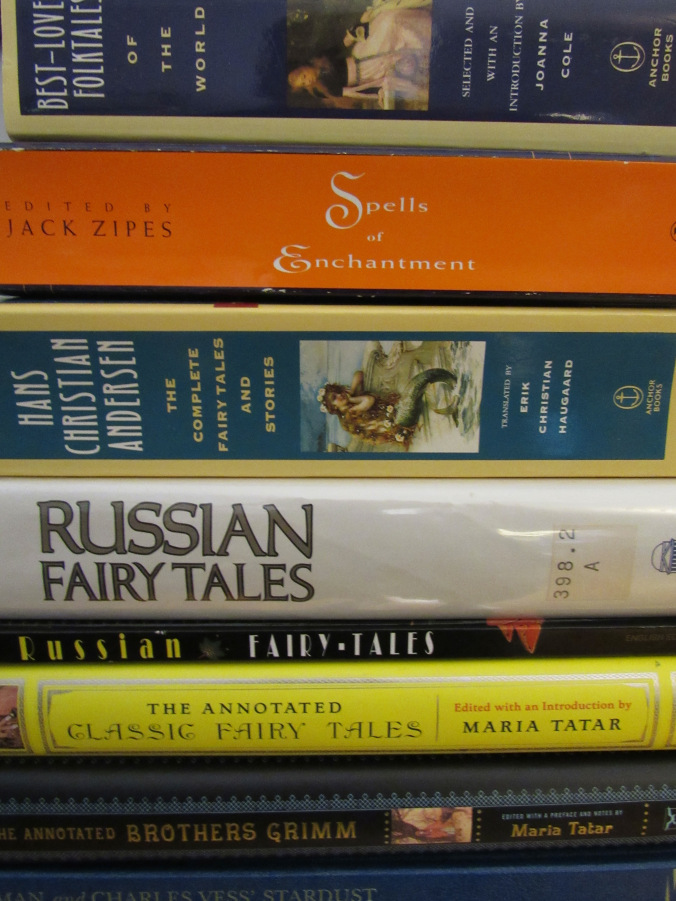

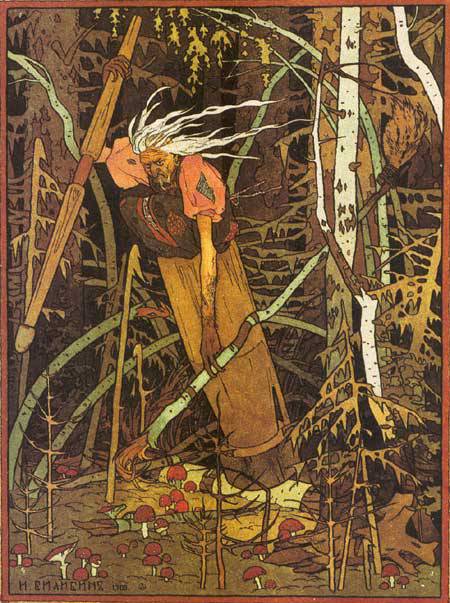

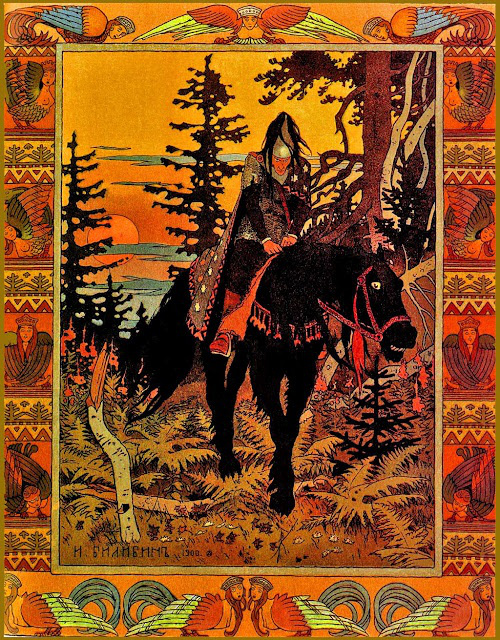

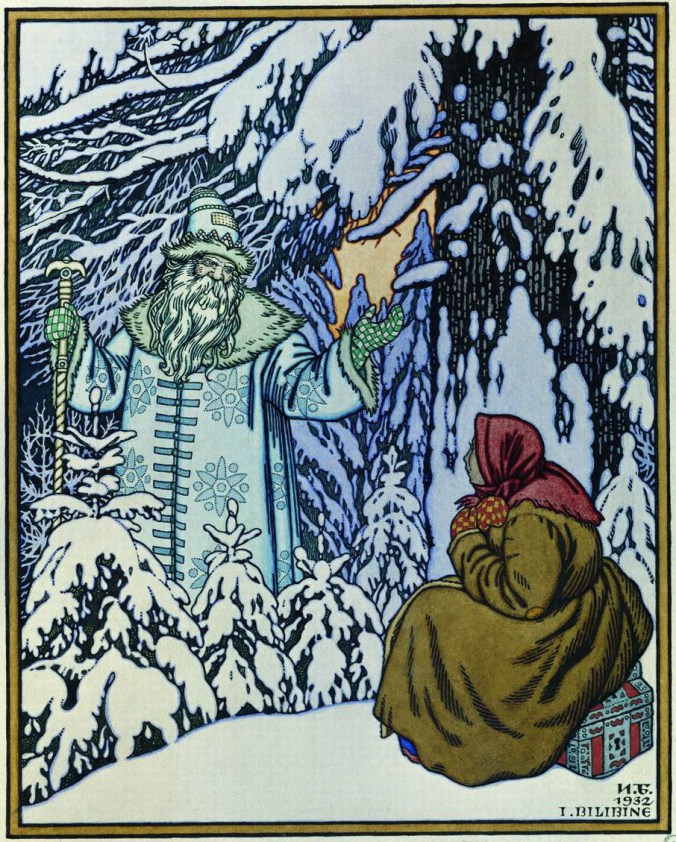

Since my son is from Ukraine, we decided to use the Slavic myths and fairy tales instead of the more European ones that most people know. Ours would be inhabited by the figures of Russian and Ukrainian fairy and folk tales. Figures like the Baba Yaga, the firebird, Father Frost and Kot Bayun. We would also add our own twists on them: creating our own characters and takes on established figures and motifs that run throughout all of Slavic folklore and mythology.

What’s fascinating about writing this fairy tale is how much of it we incorporate with ourselves and our own struggles masked in the archetypes of a character like the crone Baba Yaga or the forest itself. I love how Maria Tatar describes this process in her book Enchanted Hunters: The Power of Stories in Childhood:

“Magic happens when the wand of language strikes a stone and makes it melt, touches a spindle and turns it into gold, or taps a trunk and makes it fly. By drawing on a syntax of enchantment that conjures fluidity, ethereality, flimsiness, and transparency, writers turn solidity into resplendent airy lightness to produce miracles of linguistic transubstantiation.

What is the effect of that beauty? How do readers respond to words that create that beauty? In a world that has discredited that particular attribute and banished it from high art, beauty has nonetheless held on to its enlivening power in children’s books. It draws readers in, then draws them to understand the fictional worlds it lights up.”

The reason fairy tales have stayed with us and have had such a deep impact on those who both read and hear them is that they connect to something primal about us. They strike a chord of truth within us that we understand that there is darkness and light, and that the choice determines our characters and our outcomes. Fairy tales show us that kindness is rewarded and selfishness leads to destruction. We are enchanted by these stories because they reveal truths to us that we cannot find anywhere else.

Who doesn’t delight upon hearing the words, “Once upon a time . . .”

Walt Disney built so much of his empire on them.

Our culture thrives on fairy tales disguised as dramas or even advertisements. Nikes are the magic shoes that give us amazing athletic prowess. Coke is the magic elixir we drink and find friendships. Wear this makeup and it will make you look younger and more beautiful than all of the other fair maidens.

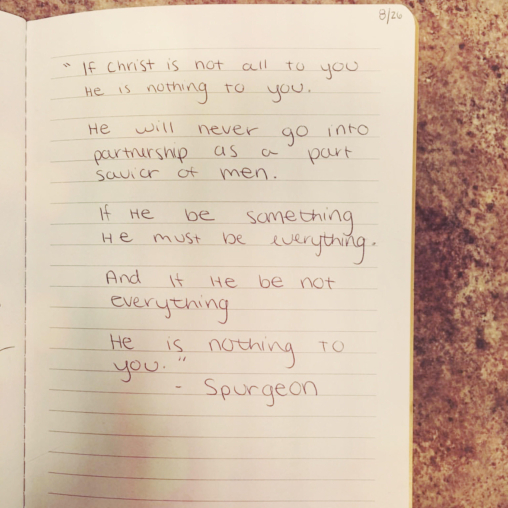

We need fairy tales because we long for them to be true. As Jack Zipes wrote, “If there is one ‘constant’ in the structure and theme of the wonder tale, it is transformation.” We all long for transformation. Is it any wonder we keep retelling the tale of Beauty and the Beast?

And I hope for transformation, even tiny glimpses of transformation, in my younger son as we write this tale together. It is the opportunity to not only spend time together creating and allowing him to discover the true limitlessness of his imagination (something he had never been able to do before he was adopted), but hopefully find some healing in the power of storytelling. As G. K. Chesterton wrote, “There is the great lesson of ‘Beauty and the Beast,’ that a thing must be loved before it is lovable.” This is a lesson he’s learning by being a member of our family and our community.

Fairy tale characters struggle to overcome witches and monsters and bestial forces, but this child has really faced the demons and the darkness that exist in the forest of this world. We are going through our imagined forest together, writing of a young boy who defeats his enemies, makes friends in those he encounters (human, animal and bird), and, ultimately, overcomes and triumphs. I hope that the story he is helping me write is one that will resonate within his own mind and heart and soul. I want him to see that he is the boy, Pavel, from our story. He is a hero. He is truly braver than the knight Ilya Muromets.

‘Words,” Maria Tatar writes, “have not just the astonishing capacity to banish boredom and create wonders. They also enable contact with the lives of others and with story worlds, arousing endless curiosity about ourselves and the places we inhabit.”

And they do.

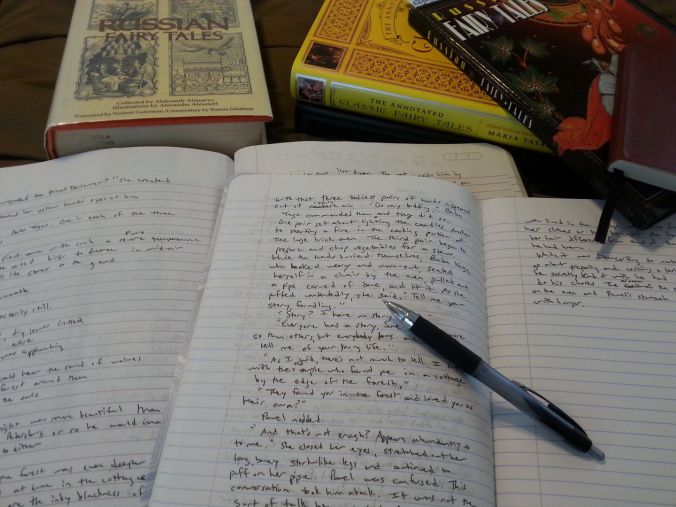

My younger son and I sit on my bed with all of our notes scribbled in notebooks spread out and all of my fairy tale books within reach and we talk and write and dream and imagine. We create worlds and characters and scenarios of terror and wonder. This is, indeed, the true magic of fairy tales.

Advertisements Share this: