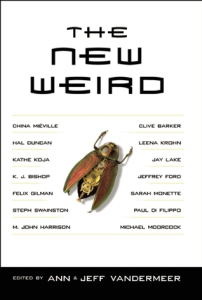

Editors: Ann VanderMeer and Jeff VanderMeer

Type: Fiction, short stories (anthology)

Published: 2008

I read it: September 2017

When I first read Jeff VanderMeer, I was also reading H.P. Lovecraft for the first time. Because of that, and because of my limited exposure to authors in this vein, I over-attributed much of VanderMeer’s craft to the influence of Lovecraft. I eventually found a podcast in which he claimed not to be a fan of, or very familiar with, Lovecraft at all. This still strikes me as dubious, and the sense I got was that he was just tired with the one-note comparison and wished people would stop using the Lovecraft shortcut in analyses of his work. Fair enough.

I had gleaned that VanderMeer was part of something called “weird fiction,” so when I happened to walk past this one at the library I snagged it to learn a bit more about the genre. Or movement? Or whatever you call it. In the intro, Ann and Jeff try to explain the evolution around the discussion of the term “New Weird,” which was occurring mostly in the early 2000s by the writers who were a part of it. At one point they try to actively distance the qualities of modern weird fiction from Lovecraft and other early horror writers: “New Weird relies for its visionary power on a ‘surrender to the weird’ that isn’t, for example, hermetically sealed in a haunted house on the moors or a cave in Antarctica.” This anthology makes very clear that the modern popularizer is China Miéville, in his novel Perdido Street Station. And by the time this anthology came out the point was already moot, with most of the wily authors involved reluctant to fully embrace the label. In fact, the VanderMeers end their introduction with “New Weird is dead. Long live the Next Weird.” And that statement was a decade ago.

But the trickiness of the term didn’t stop the editors from putting their favorite pieces on display. Off the bat, M. John Harrison sets somewhat of a template with “The Luck in the Head,” which includes many of the features of the genre: a focus on bodies, on cities, on magic that is almost scientific, or vice versa. There’s a lot of foreboding and danger both vague and specific. Similar vibes are found in “The Braining of Mother Lamprey” by Simon D. Ings, the brutal “The Gutter Sees the Light That Never Shines” by Alistair Rennie, or Jeffrey Ford’s “At Reparata,” although that one reads a bit more like a colorful parable. Some stories focus on workers, caste, and backstabbing, including both China Miéville’s crackling “Jack” and Jeffrey Thomas’ “Immolation.” I’d read Brian Evenson before, and his “Watson’s Boy” is an unsettling slow burn that is somewhat impenetrable but still intriguing. I didn’t quite click with Michael Moorcock’s “Crossing into Cambodia,” but I’m sure glad I found Clive Barker’s “In the Hills, the Cities,” which envisions cities battling each other by the citizens lashing themselves into single representative giants. One of the most truly weird in this set of weird stories is Jay Lake’s “The Lizard of Ooze.” If you can descend into the grimy depths along with the protagonist of this story, you’ll have a good sense of the layers that the New Weird can wrap around you.

This book is not a short one, and after getting through about two-thirds of it I considered stopping, feeling I had gained a good sense of the New Weird through the lens of 2008. But I’m glad I pushed through to the end sections, which include online discussions of the term among those authors involved (some who have stories in this book). Stephanie Swainston describes the genre as such:

The main influence is modern culture—street culture—mixing with ancient mythologies. The text isn’t experimental, but the creatures are. It is amazingly empathetic. What is it like to be a clone? Or to walk on your hundred quirky legs?

These authors’ thoughts on broader literary versus science fiction discussion are fascinating as well. Justina Robson says “I think that Literature is going to come to SF and try to take the entire thing over by main force in the next five years. I think has to happen, because the world has turned into a SF world.” This seems to have happened as predicted. Take an ostensibly traditional sci-fi website like Unbound Worlds, and you will see it including anything and everything “literary” that fits any definition of fantasy and science fiction. And what a positive thing this has been: the genres get murkier no matter how badly we want to keep the shelves labeled in an orderly way, and good writing is recognized as good writing regardless of content.

Finally, this book includes short interviews with overseas editors and asks them their thoughts on the New Weird phenomenon (if it even exists in their home countries, that is). Even before knowing about this section of the book, I had recognized what I could only describe as the “Europeanness” of so much of the New Weird stories. The old rambling cities full of history and mystery, crowded with cobblestone, ivy, and intrigue, seem alien to America. Anyway, Romanian editor Michael Haulica offers another insightful angle to the genre discussion and why the New Weird in particular has drawn various readers:

For me, New Weird is science fiction, fantasy, and horror mixed together, with a literary approach. That’s why the New Weird authors transcend the genres and anger the “hardcore” fans, especially the fans of any genre who feel they and their devotion have been betrayed by these authors. In the meantime, New Weird authors seem to forge greater alliances with “mainstream readers”—those who usually don’t read genre fiction but do read these weird tales because they are extremely well-written, like any other kind of “high literature.”

Therefore New Weird novels are the literary shuttles between two worlds: genre and mainstream. They form first contract expeditions, and, in some cases, the second and third contacts come soon after.

The literary shuttles: I can’t think of a better way to describe how these types of stories glide between book store shelf categories, drawing readers from otherwise separate corners. To read a New Weird story is to be fed multiple ideas and textures all at once, as if you are hungry for something you never knew to be hungry for. As a character in K.J. Bishop’s “The Art of Dying” puts it to a clinging journalist, “What do you think it is about people like us…that so fascinates the good citizens of this town? That they will take an interest in what you write tonight, I have no doubt; but out of what matrix of habit, hope, imagination, appetite?”

Habit, hope, imagination, appetite. The matrix of why we read, genre be damned.

Advertisements Share this: