On Monday I attended the ‘Stuff of Research’ symposium at Kelvinhall in Glasgow, the culmination of the year long material culture research programme organised by SGSAH. (You can find out more about the programme and previous events in these blog posts: here, here and here.) The day was organised by students who had taken part in the programme, and featured 12 speakers, a ‘making’ session, the option of a card game or walking tour, and ended with a keynote from Professor Ivan Gaskell of the Bard Graduate Centre, New York. It was a full programme, and the panels were very mixed in terms of subject matter, with topics ranging from the collecting habits of Sir Walter Scott to coding custom software for the display of digital artworks.

Playing ‘The Monument Game’, at the Stuff of Research symposium – devised as part of a research project by Laura Donkers

I attended the event as a speaker, and gave a paper on my research into practical fashions and synthetic fibres in the First World War. We all know how hit and miss the questions following a conference paper can be, and so I was very pleased to get a genuinely interesting and insightful question about the objects I work with as part of my research process.* My paper was all about the active properties of fabrics and garments designed to ease or aid women’s lives in the war period, so how do I equate the need to understand the active and functional properties of these objects while also doing them no harm when handling/studying them as part of the research process? How can these properties be conveyed in the interpretation and display of objects with the same conservation considerations in mind?

These are questions that I do touch on (pun not intended!) in the final chapter of my thesis, which focuses on the issues surrounding the display and interpretation of FWW garments in a museum setting. But originally, my PhD project looked very different, and was going to be primarily focused on the concept of touch: how we understand objects through tangible engagement; the power of the senses; and the stories that can be told through texture and form. Overall I was interested in the ability of objects to tell stories, and whether this could happen with less words and more interaction. My PhD proposal was heavily inspired by my own background as a maker, the material culture module I took on my Masters programme, and Edmund de Waal’s beautiful family memoir The Hare With Amber Eyes.

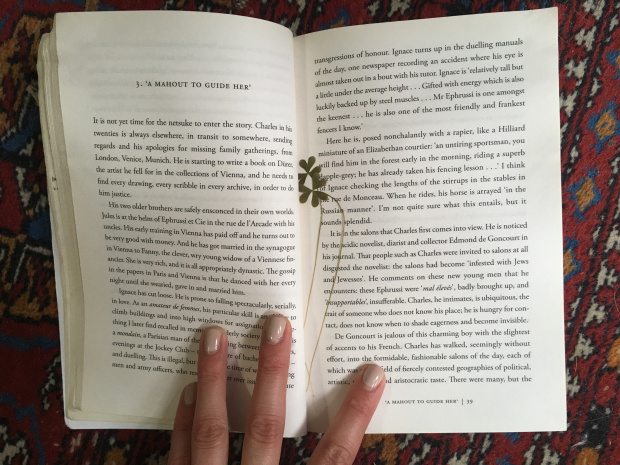

De Waal, known not only as a writer but also as a gifted ceramicist, is wonderfully in tune with the handle of objects. He writes, for example, that while researching the collections of his ancestor Charles Ephrussi, he began ‘to feel his pleasure in stuff […] the surprising weight of damask, the chill of surface enamels, the patina of bronzes, the heft of the raised thread on the embroideries.’ (1) Later in the novel, he goes on to speak of the ‘patina’ of stories, suggesting that ‘patina is a process of rubbing back so that the essential is revealed, the way that a striated stone tumbled in a river feels irreducible, the way that this netsuke of a fox has become little more than a memory of a nose and a tail. But it also seems additive, in the way that a piece of oak furniture gains over years and years of polishing, the way the leaves of my medlar shine.’ (2)

Pressed clovers found in my copy of The Hare With Amber Eyes, previously read by my mother and grandfather

Before any conservators reading this start to panic, I do not think that we should all be able to walk around museums touching the objects on display. (One of the reasons that I very quickly changed my PhD project!) However, I do think it is important that the display of objects works hard to convey the “extra-material meaning” (3) of the items on display. Curators and researchers are incredibly privileged to have hands-on access to collections. We get to visit the stores, open boxes, and feel the weight, texture and handle of objects. We can even smell them – which is sometimes not a privilege in the case of dusty, sweat-stained old frocks! I appreciate that not every museum visitor will be enamoured with descriptions of the stiffness of a collar, or the slippyness of a fabric, but this kind of information can be transporting when trying to imagine the object in it’s original context; on a body, against the skin, in action. A similar issue was raised at the symposium by David Gerrard from the University of Edinburgh, in his paper on the reconstruction and repair of historical musical instruments. He made the point that to be truly understood, musical instruments need to work. Without functioning to produce a sound, only part of their meaning can conveyed.

David Gerrard speaking at the Stuff of Research symposium

I have been incredibly lucky that the majority of collections I have worked with over the course of my PhD have allowed me to handle garments and textiles in order to inspect them fully, to get an idea of their weight and the way they move, and identify the fibres used in construction. This last point was particularly vital in my research on synthetic fibres, which can sometimes be very difficult to identify. But because I have been allowed close contact with these objects – gently assessing the feel of the fabric with my hands and using a magnifying glass to observe the fibres making up warp and weft – I have been able to identify certain branded fabrics and contribute information to object records in museums. One day I will get to share my findings more widely.

Close study of fibres at Platt Hall Gallery of Costume, Manchester

So I would argue that, where reasonable, researchers should continue to touch and handle the objects they work on, because by doing so we can add greatly to their value and their ability to tell stories. For those working in material culture, our responsibility is to interpret objects so that they become meaningful both within our institutions or fields of academic study, but also for wider audiences. There is a great pleasure in stuff, and if we can balance our explorations of materiality with the need to preserve, then the enjoyment of stuff will be enhanced both for ourselves and for future generations.

Advertisements Share this:*Thanks to Murray McLean for asking the question that inspired this blogpost! The ‘Stuff of Research’ organisers also created a Symposium Newsletter’, which you can access here.