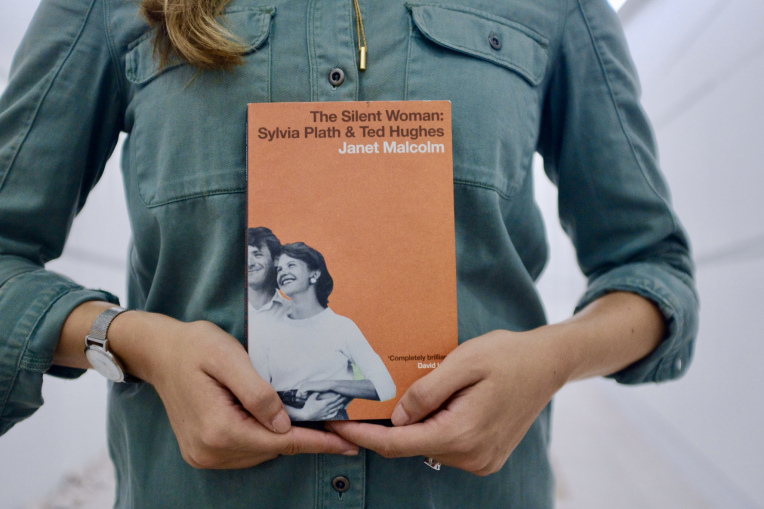

“Biography is the medium through which the remaining secrets of the famous dead are taken from them and dumped out in full view of the world. The biographer at work, indeed, is like the professional burglar, breaking into a house, rifling through certain drawers that he has good reason to think contain the jewelry and the money, and triumphantly bearing his loot away.” (Janet Malcolm, 1993)

“Biography is the medium through which the remaining secrets of the famous dead are taken from them and dumped out in full view of the world. The biographer at work, indeed, is like the professional burglar, breaking into a house, rifling through certain drawers that he has good reason to think contain the jewelry and the money, and triumphantly bearing his loot away.” (Janet Malcolm, 1993)

Janet Malcolm writes like a giant throbbing brain on the page. Although she calls herself an investigative journalist, her stories are less concerned with the who, what, where, and more concerned with the why. She reports on phenomena and philosophizes about the work of writing. In The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes (1993), instead of writing a biography about the two poets, she investigates the complications of literary biography. Malcolm argues, among many things, readers of literary biography need to be more vigilant and not read with, as she says, “bovine equanimity”(look it up!).

I have read her most famous book, The Journalist and the Murderer, for my master’s degree and was excited to begin another with a topic that fascinates me.

Slyvia Plath was an American writer and poet whose first and only novel, The Bell Jar, – although torn apart in this book for poor writing – was one of my favorite books in high school. My two BFFs loved her as well, the whole melancholy misunderstood white girl thing really spoke to us. She was mythic in my imagination, the scorned woman, the tortured artist, the not-nice girl, and we lived in the Midwest where there weren’t adults to correct us and say, “Dylan Thomas and Ted Hughes are so much better! The British are so much better! Don’t read that silly, American, girlish confessional poetry!”

I’ve since ‘learned’ her books and poetry aren’t appropriate for serious adult readers, but somehow feel a bit miffed at the points where Malcolm loosely claims that Plath is only famous because she killed herself. It is worth considering that Plath possibly would not have become famous if she did not have this dark aura around her life and death. But maybe, if she had lived, she wouldn’t have become famous because her work would be overshadowed by her role as ‘the first wife of Ted Hughes’ – the Poet Laureate. (Similar to one of my other favorite writers, Martha Gellhorn, who was an excellent journalist known better for being Ernest Hemingway’s third wife.)

A quick refresher for readers not familiar with Plath’s story – after finding Hughes, her husband at the time, with another woman she kicks him out of the house and begins living alone with her children. A few months later, she commits suicide. Since Hughes and Plath were still married at the time of her death, Hughes inherited her whole literary estate. He burned the journals from the last few months of her life (he says to protect his children, skeptics say to hide evidence of his physical abuse), but keeps the rest of her works. He (and his sister working as his and Plath’s estate agent) publishes her novel, The Bell Jar, in America and allows Plath’s mother permissions to publish correspondence between them. Then, Hughes publishes Plath’s personal journals with omissions.

Alongside this publishing drama, many other writers try to tackle Plath’s story by writing memoirs or biographies but have to deal with Hughes if they want permission to use any of Plath’s writings. Of course, not every biographer is sympathetic to Hughes, and this leads to many angry letters, threats, and legal action. Of course, Malcolm publishes many bitchy letters (mostly from Ted), interviews various biographers and memoirists, and Hughes’ sister and literary agent, Olwyn Hughes.

I was fully prepared to read a gossipy book about Sylvia, Hughes, Hughes’ sister, Plath’s mother, the people who have written about their relationships and work.

But what continually draws me into Malcolm’s writing is her ability to make more out of a story. Beyond the ‘who said what and when,’ Malcolm added a layer of literary critique to the world in which they were all living in. Plath is depicted as a foreigner in a foreign land (which as a fellow American in Britain, I could relate to on many levels, as could Anne Stevenson, the author of Plath’s most controversial biography) but also as leading a nineteen-fifties American female double life. This was a time when the facade was all clean apartments and home-cooked food, but underneath was unhappiness and unfulfillment. It was a time when some women thought they should be able to balance being an ideal middle-class housewife and a creative, but in many ways couldn’t. (Many female creatives before the mid-twentieth century tended to come from the wealthiest families, as it gave them the freedom from childcare, homework, and economic repercussions for ‘acting out.’)

A final biographical note. Janet Malcolm attended the University of Michigan at the same time as my late paternal grandmother, Patricia Kienbaum, at a time when very few women went to university. I have fantasies that my grandmother and Malcolm knew each other in some way, that Janet would one day take me under her wing and we could reminisce about my grandmother together. I would become a disciple to her New York literati, and Grandma Pat would look down smiling from heaven or wherever.

In the same token, my grandmother was the daughter of a postal worker, not a professor like Malcolm. At the University of Michigan, she started studying foreign correspondence, but eventually switched to a teaching degree. She lived in a co-op, where she had to clean for other students to pay her way and became pregnant shortly after.

Grandma Pat was tied to Michigan for the rest of her life, until retirement when she traveled the world with my grandfather. It was then I appeared on the scene, the oldest child of her youngest son, who liked books and languages and writing as well. She gave me the idea that could travel too, I could go to Europe, I could leave, like Malcolm, like Anne Stevenson, like Sylvia Plath, and hopefully, I could make something of it. That was why, selfishly, the most enjoyable part of The Silent Woman was reading about women similar to my grandmother; the story about writers developing around the same time at Plath, reinventing themselves, trying and, sometimes failing, to be a woman and an artist.

I have loads of other thoughts, but I try to keep these things short, and I’m already at 1,000 words! So just email or message me if you read the book and want to discuss.

Share this: