By Nathen Amin

Although Christmas traditions in the UK appear set in stone, for example the tree, the songs and the food, it’s very much been an evolving process since the earliest days we started marking the birth of Jesus Christ. The way the Tudors celebrated Christmas, quite literally ‘Christ’s Mass’, was quite different to the way we do today, although the core concepts of family and feasting are still very much visible.

So how did Henry VII mark the Christmas period in 1487, 530 years ago? Thanks to the antiquarian John Leland (1503-1552), who transcribed a collection of manuscripts in his work Collectanea (1533-1536), we do have some insight into how Christmas was celebrated that particular year. The key thing to note is that, unlike today, the Christmas festivities truly began on Christmas Day, and lasted until 6th January (the Feast of Epiphany), hence the Twelve Days of Christmas. The Tudors definitely weren’t preparing for Christmas as early as October as we do today.

1487 had not been an easy year for Henry VII; his crown, even his life, had come under severe threat from hostile forces within and without his kingdom, although the resilient king ultimately succeeded in punishing his enemies’ ‘unrighteous fury’, as Bernard Andre triumphantly put it. Henry had spent the first six month of the year preoccupied with the Lambert Simnel conspiracy, finally defeating his adversaries at the Battle of Stoke Field, before focus shifted to solidifying the Tudor crown through the agency of the November parliament. A key part of securing his position was to order the coronation of his wife Elizabeth of York, ‘for the perfyght love and syncere affeccion that he bare to his queen’.

Rebellions, battles, parliaments and coronations, one imagines Henry VII looked forward to the Christmastide that year, which began in earnest when he departed Westminster around 18 December for Greenwich Palace ‘wher he kepte his Cristemasse ful honorably as ensueth’. The preceding few weeks, from the first Sunday after St Andrew’s Day (27th November), had been spent fasting three days a week, known as Advent, as each person spiritually prepared for Christ’s ‘Second Coming’ on Christmas Day. One imagines that by the end of this period, the court were ready to let loose for Christmas, the one-time of the year the strict protocols in place in Tudor society relaxed somewhat. That said, religious duties were always observed carefully. Leland’s manuscript goes on to recount how:

‘on Cristemasse Even our saide Souveraigne Lorde the King went to the Masse of the Vygill in a riche Gowne of Purple Velvett furred with Sables, nobly accompanyed with dyvers great Estats, as shal be shewde herafter. And in like wise to Evensonge, savyng he had his Officers of Armes by or hym. The Reverend Fader in God the Lorde John Fox did the dyvyne Servyce that Evensong, and on the Morow also’.

Lord John Fox appears to be an erroneous reference to Bishop Richard Foxe, Bishop of Exeter and a churchman who Henry VII had first encountered during his exile in France. Henry had also rewarded Foxe early in his reign by appointing him his first Secretary of State, and also Lord Privy Seal. The following day, which was Christmas Day, the king celebrated with a dinner in the ‘great Chambre nexte the l. Galary’, whilst ‘the Quene and my Lady the Kings Moder’ with their ladies had their meals in the Queen’s Chamber.

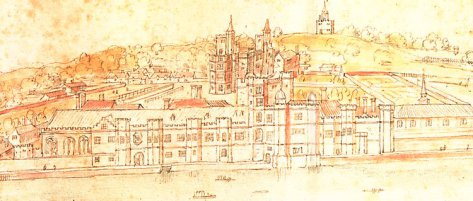

Greenwich Palace

Greenwich Palace

What followed were several days of festivities, with musicians, pageants and plays entertaining the court at Greenwich. Although not mentioned in Leland’s Collectanea, 28th December was the Feast of the Holy Innocents, marking King Herod’s decree in the Bible to slaughter all babies born within three days of Christmas, and traditionally this was commemorated with the merriments that included role reversal. A Lord of Misrule was typically selected from the commoners to act as king, overseeing a night of rowdy drunkenness and revelry to the entertainment of the court. Although the custom would eventually be banned under Henry VIII, his father Henry VII was fond of the occasion, and although payments to a Lord of Misrule appear in his household accounts from 1491, there is every possibility such a spectacle took place in some capacity during 1487.

Other activies known to have been enjoyed during this period were playing the harp or lute, and games such as backgammon, chess and cards. There is evidence Henry VII lost money playing cards during his reign, so we know he enjoyed the pursuit, although whether he enjoyed losing his money is another matter. The Croyland Chronicle criticised Richard III for the raucousness of his Christmas court in 1484, but there seems little reason to suggest Henry VII didn’t follow in a similar manner. The Croyland Chronicler was, after all, a churchman, who may have looked unfavourably upon the court letting loose with wild abandon.

The Collectanea is sadly lacking in regards to what food was enjoyed this particular year by the king and his court, but boar’s head garnished with rosemary and bay leaves was a popular fifteenth century dish at Christmastime. As with the rest of the year, however, the season and weather often dictated what was available to eat, and typical winter fare during the middle of December would have included other meats such as beef, pheasant, partridge, venison, goose, duck, and rabbit, along with cheese, bread and a variety of sweetmeats and spiced cakes. One notable dish available was known as frumenty, a pudding made from boiled wheat, cream, mace, nutmeg, barley, eggs and milk often flavoured with almonds, currents and the like.

On New Year’s Day, meanwhile, the traditional day of gift giving in the Tudor court rather than Christmas Day like today, the royal family, their household and much of nobility congregated in Greenwich Palace’s Great Hall. King Henry, ‘being in a riche Gowne, dynede in his Chamber’ before, ‘of his Largesse’, or generosity, he oversaw the gift-giving ceremony, the recipients of whom this year appear to be his Officers of Arms.

According to the Collectanea, the king himself granted gifts to the value of £6, with the queen providing an additional 40 shillings, Lady Margaret Beaufort 20 shillings, and Jasper Tudor, the king’s uncle and duke of Bedford, also providing 40 shillings. Others followed suit in giving monetary gifts of varying amounts, including the Duchess of Bedford, Bishop Foxe, the Earls of Arundel, Oxford, Derby, Devon and Ormond, lords Welles and Strange, and Sir William Stanley. Thereafter, ‘on Newres Day at Nyght ther was a goodly Disgysyng’, whilst it was noted that ‘this Cristmass ther wer many and dyvers Playes’

Christmas Day and New Years’ Day were two of the three big feasts of Tudor Christmastide. The third took place on Twelfth Night, or 5th January, to celebrate the Feast of the Epiphany the following day, which commemorates the adoration of the Magi before the baby Jesus. The evening before, King Henry went to Evensong ‘in his Surcoot outward, with Tabert Sleves, the Cappe of Astate on his Hede, and the Hode aboute his Showlders, in Doctors wise’. For this particular service, the king was the only person robed, with the religious duties handled by his close confidante John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury.

On the morning of 6th January, Henry rose early for Matins prayers, and this time all his nobility were resplendent in their finest surcoats with hoods, following the crowned king and queen in procession. Margaret Beaufort also bore ‘a riche Coronall’ whilst Jasper Tudor was handed the honour of bearing the Cap of Estate before the king, alongside which walked the earls of Derby and Nottingham, Earl of Derby, with the duke of Suffolk and Giles Daubeney following close by. John de Vere, the Earl of Oxford, meanwhile, was afforded the honour of bearing the king’s train wherever he went. Following thereafter including members of the royal household, including the Garter King of Arms, the King’s Secretary, and the King’s Treasurer, along with many other employees such as Officers of Arms, Heralds, Pursuivants and those of more menial positions such as carvers and cupbearers.

Once Mass was observed by all, King Henry returned to his chamber for a period, possibly to refresh and change clothes, before returning to the Great Hall, where:

‘He was corownede with a riche Corowne of Golde sett with ful many riche precious Stonys, and seated under a merveolous riche Cloth of Astate, having the Archbishop of Canterbury on his right Hande, and the Quene also crowned under a Cloth of Estate hanging sumwhat lower than the Kings, on his lift Hande’.

Waiting on the king during the subsequent feast was the earl of Oxford, whilst the earl of Ormond kneeled between the queen and Lady Margaret, the king’s mother. Sir David Owen, the king’s paternal uncle, acted as the king’s carver throughout the day. After the second course of food was completed, and once the minstrels had finished playing, the Officers of Arms descended from their stage and the Garter ‘gave the King Thankings for his Largesse, and besought the Kings Highnesse to owe Thankings to the Quene for her Largesse’.

Elsewhere in the Great Hall, in the middle was a table which sat the dean and other churchman associated with the King’s Chapel, who after Henry had completed his first course ‘sange a Carall’. On the right-hand side of the hall was another table headed by Jasper Tudor, who was seated alongside Giles Daubeney, the duke of Suffolk, the earls of Arundel, Nottingham and Huntingdon, the king’s half-uncle Viscount Welles, Viscount Lisle, and an array of other barons and knights. On the opposite side of the hall was another table, headed by the queen’s sister Lady Cecily, who was accompanied by the countesses of Oxford and Rivers and many other ladies and gentlewomen.

Another ancient tradition likely to have been observed during this 1487 Christmas was wassailing. The act of wassailing took place during Twelfth Night, and involved the lord offering his guests a drink from a communal wooden cup, typically cider, beer or a warm spiced ale known as lambswool. Just seven years later, the act of wassailing was included in Henry VII’s household ordinances, detailing how:

“and as for the wassell, the Steward and the treasurer shall come forward with their staves in their hands, the King’s swere and the Queen’s next, with their towells about their necks, and noe man beare noe dishes but such as be sworne for the mouthe”.

It was further declared that “when the Steward comethe in at the hall doore with the wassell, he must crie three tymes, wassell, wassell, wassell”. There seems little reason to doubt that this took place during the 1487 Christmas.

Once everyone had eaten, been merry and entertained to their hearts content, the end of the evening brought the Christmastide festivities of 1487 to a cheery close, a Merry Christmas having been had by one and all. The following morning, however, thoughts returned once more to the more tedious aspects of governing the realm, at least until the next holiday of note. Not unlike the modern day, one must imagine!

________________________________________________________________________________

Nathen Amin grew up in the heart of Carmarthenshire, West Wales, and has long had an interest in Welsh history, the Wars of the Roses and the early Tudor period. His first book Tudor Wales was released in 2014 and was well-received, followed by a second book called York Pubs in 2016. His third book, the first, full-length biography of the Beaufort family, the House of Beaufort, was released in the summer of 2017 and quickly became a #1 Amazon Bestseller for Wars of the Roses.

Advertisements Share this: