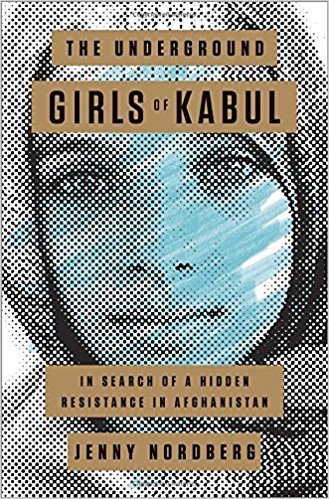

Since 2001, when a coalition led by the U.S. invaded Afghanistan, a lot of attention was paid to the “rebuilding” of the Islamic republic. Most of what we hear in the news is focused on the deprivation, constant skirmishes between Taliban (and Taliban adjacent groups) attacking Western forces, corruption, and deplorable conditions for women and girls. It sounds like an overwhelmingly hopeless situation. Jenny Nordberg acknowledges these dire situations, but explores the nuances and reveals that even in such hopelessness, there’s small rays of resistance and hope still trying to take root.

She frames this novel around several Afghani women and the story of their lives. One, Azarita, is a parliamentarian. In getting to know her family, she’s informed by the oldest twin sisters that their youngest brother isn’t a boy, but a girl. Nordberg investigates further and discovers that indeed the youngest child was born a girl, but has been presented to society and her family as a boy. She receives the priviledge of being a boy in the patriarchal society even though everyone knows that shes a girl. This concept fascinates Nordberg. As she investigates further, she realizes that there’s many girls who present as boys, called bascha posh, until they hit puberty and are then changed back into girls. In most cases, these girls are made into bascha posh because the family needs more income and only boys can work outside the home. There’s also a myth that if a daughter is bascha posh, then the next child will be a legitimate boy.

However, not all girls decide to change back into women when they hit puberty. A few decide that they do not want to give up their freedom and priviledge to be married off and be chattel to their husbands producing child after child. Many pass as long as they can until either their bodies no longer permit them to pass or their families force them. A few remain bascha posh until they are passed child bearing age. Nordberg found that even in a society that values boys over girls, these bascha posh are accepted as boys even though everyone knows they are born girls. This baffled me because it seems counterintuitive to a society that women are kept separate from boys and are viewed as merely a means to perpetuate bloodlines and produce boys, or girls that can used to barter debt or high bride prices. Yet it seems in Afghanistan that the society is willing not to question the decision parents make about how they present their child’s gender. It’s as if they are all complicit in perpetuating an illusion. These bascha posh are allowed to work, to be educated, to fight, to foster and maintain male friendships; everything that a natural-born boy would be able to do.

Nordberg investigated to see if this was a phenomena only in Afghanistan. She found that this is unique only to cultures that perpetuate strictly opressive patriarchies. That is nations like Albania and Montenegro there are women who are allowed to present themselves as men and access the male priviledge. Even in Western cultures there are examples like Joan of Arc who wore male battle gear and took the role of a military commander. There’s countless examples of women who passed as men to fight in wars. With the relaxation of the oppression of women, the need to pass as men has lessened, but Nordberg points out that in many cases, politics, business, and many other professions, Western women are still not allowed to be fully feminine. Nordberg points out too that in building Afghanistan’s democracy, the West imposed a 25% female representation in parliament, even though the U.K. only has 22% and the U.S. 15%. This shocked me and made me confront the hypocrisy the West gets itself into when building so called uncivilized nations. We don’t always practice what we preach.

While the situation of many of the women and bascha posh seems dire, Nordberg points out that there are rays of hope. The fact that there are still fathers who want more for their daughters than to be another man’s chattel. Instead of trying to focus solely on women and girls, Nordberg suggests that the nation builders include men in the conversation of gender quality. When men realize that women contribute to successful economies and that educated women are a matter of pride, men won’t see women as something to be ashamed or afraid of. And when the pressure to maintain a family’s status doesn’t rest solely on men, they too can progress and together men and women can help build Afghanistan into a safe, functioning nation.

Nordberg’s point about including men in the discussion of gender equality really hit home, especially in light of the #Metoo campaign and the call to restructure how we talk about sexual harrasment and assault. Too often we frame it around women in the passive voice. We need to include men in the discussion and empower them to confront the men who perpetuate this violence and discrimination. We can’t point fingers at the men of Afghanistan if we aren’t willing to confront the men in our own backyard.

Advertisements Share this: