By Cassie Watson and Laura Sellers; posted 19 December 2017.

Thomas Scattergood, the son of a Methodist clergyman, was born in Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, in 1826. In 1846 he was appointed to the post of assistant apothecary at the General Infirmary in Leeds, subsequently qualifying as MRCS and LSA, and then going into general practice in Leeds early in 1851, the same year he became a lecturer in chemistry at the Leeds School of Medicine (established 1831). From 1869 to June 1888 he lectured in forensic medicine and toxicology, “in which subjects he attained such eminence that as an expert his advice was constantly sought in medico-legal cases not only in Leeds, but in Yorkshire and in the North of England generally”.[1] He was instrumental in the amalgamation of the Medical School with the Yorkshire College (est. 1874) and became the first Dean of the new Faculty of Medicine in 1884, a post he held until his death in February 1900.[2]

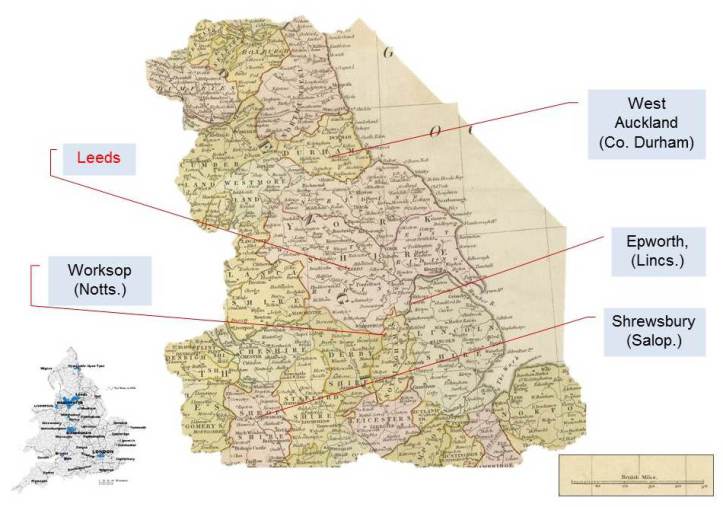

The Brotherton Library at the University of Leeds, as the Yorkshire College became in 1904, now holds three notebooks in which Scattergood recorded his medical and forensic work. The first two cover the majority of his forensic cases and make it clear that Scattergood was being sent samples for forensic analysis from across a wide area of the country. One of the key developments that facilitated forensic practice in the nineteenth century was the expansion of the rail network: it became fairly common for forensic samples taken by a local medical practitioner to be sent from the scene of a suspected murder to a toxicologist by post, or sometimes via a police officer who travelled by train.[3] By the time Scattergood became active as a toxicologist in the 1850s, England — particularly industrial areas such as Leeds — was well served by a fast-growing rail network. The image below shows some of the geographical range of Scattergood’s forensic practice; the small map at bottom left shows rail lines in 1854.

Most of the cases recorded in these notebooks are dated and have titles; they contain detailed notes about the specimens provided to Scattergood, the testing undertaken, and the results of his findings. There are often notes in the margins of each case, some sketches, and many include related newspaper articles about inquests or committal hearings. While Scattergood was not exclusively concerned with poisoning cases, they do make up a large proportion of the contents of both volumes, and include poisoning by strychnine, croton oil, arsenic, lead, opium and laudanum, cyanide, aconite, phosphorus, zinc sulphate, silver nitrate, oxalic acid, sulphuric acid, morphine, chloral and potassium bromide. Strychnine and arsenic cases were the most common, probably because so many of Scattergood’s cases involved criminal intent or negligence — both were used as ingredients in commercially available vermin killers. However, there were fewer human than animal victims; the latter included horses, cattle, dogs, foxhounds, chickens, pigs, pheasants, partridges and even a rat.

Volume 1 covers May 1856 to September 1874, opening with a case from Hertfordshire, the only one from so far south of Leeds. Volume 2 covers 1875–1889; a final note about a case from 1897 shows that, on request from a doctor in Escrick near York, Scattergood sent information about a case he’d dealt with in 1869, concerning the topical application of an arsenical preparation as a cancer treatment.[4] Of course this had ended badly for both patients: in 1869 the inquest jury could not agree so an open verdict was recorded,[5] but in 1897 a herbalist was tried for manslaughter and acquitted.[6] The second volume of case notes covers mainly 1875 to 1885, almost certainly because Scattergood restricted or abandoned his forensic practice after he became dean of the medical school. Volume 3 covers the years 1840–1897 and is less organised than the other two volumes. Like the others it includes notes on criminal cases but also notes and speculations on the ways medical men could ascertain causes of death.

Strychnine

In May 1856 the country was transfixed by the trial of Dr William Palmer for the strychnine murder of his gambling companion John Parsons Cook, a case that led to significant disagreement between the large number of expert witnesses mainly because of the failure of the pre-eminent toxicologist Alfred Swaine Taylor to detect the poison in the victim.[7] Palmer’s trial marked the public arrival of strychnine on to the criminal stage, but its numerous victims were not always human, as Scattergood had discovered only the day before.

On 13 May Scattergood received a letter from a Mr Allanson of Watford, Hertfordshire. It arrived by railway, accompanying a box which held a jar sealed closed with a bladder, containing a stomach with contents and two portions of intestine from a dog. The stomach was of “unusual appearance” and Scattergood examined it for strychnine. One third was “cut small [and] mixed with water & acidulated with [acetic acid], boiled for 15 min[utes] & filtered” (an accident meant some of the liquid was lost); the rest was sent to a steam bath with alcohol— Scattergood reported that the extract had a “bitter taste” but there was no decisive evidence that strychnine was present. Another third of the liquid was heated with water and acetic acid, boiled and filtered, mixed with charcoal, boiled and filtered again. The solid residue was dried with boiling alcohol and mixed with sulphuric acid and potassium dichromate, upon which the “usual [colour] reaction of strychnine was clearly and abundantly exhibited.” The final third was tested, with negative results, for metallic poisons. On 22 May Scattergood began physiological tests using animal subjects, a newt and a rabbit; the symptoms of the latter were very carefully documented. These tests confirmed that strychnine was definitely the cause of the dog’s death.[8]

At least two of the animal poisoning cases recorded in his notebooks came through a Mr Wilson, and others from a company called Hirst and Brooke — which seems to have been a Leeds-based chemical retail company which made a variety of products including tonic wine, the advertisements for which can be found in local newspapers. Still others came via the police, or directly from landowners and farmers.

Scattergood was also consulted in a small number of murder cases. In 1875 he performed the analysis in a case of strychnine poisoning in which Elizabeth Pearson was accused of murdering her elderly uncle with “Battle’s vermin powder” at Gainford, County Durham — a crime committed apparently so she could gain possession of his furniture.[9] Scattergood received human tissue samples from the police on 23 March, eight days after the victim’s death, and eventually added a comment at the end of his case notes: “The woman Pearson was convicted of murder at Durham summer assizes, & executed”.[10]

On two occasions Scattergood made sketches of the crystals he obtained from chemical tests for strychnine. In an 1862 case involving a human victim, he received the stomach, intestines and their contents from the police, and his notes list a variety of methods for detecting strychnine. These included colour tests, the microscope, a bitter taste, a physiological test, and a negative test for arsenic. At the inquest he announced that the stomach contained Battle’s Vermin Killer, and more than enough to kill the individual. Afterwards he noted the deceased was a middle aged woman, wife of an innkeeper and that the couple did not get on, but there is no indication that a criminal case ensued;[11] perhaps it was a suicide.

With respect to the crystalline form obtained from reaction with bichloride of mercury, he noted that “crystals were formed resembling the accompanying sketch, which may be taken as like the figure given by Dr Guy (62 No.3), which he states to be very characteristic.”[12]  This was a reference to William Guy’s 1861 book Principles of Forensic Medicine, figure 62,[13] showing not only that Scattergood was consulting the most up-to-date literature but also that he obtained the expected results.

This was a reference to William Guy’s 1861 book Principles of Forensic Medicine, figure 62,[13] showing not only that Scattergood was consulting the most up-to-date literature but also that he obtained the expected results.

A Case of Serial Murder

Volume 1 contains details of the evidence Scattergood provided for the murder trial of Mary Ann Cotton (1832-1873). She was a serial poisoner who was finally caught in 1872 in the town of West Auckland in County Durham, when a local physician became suspicious and did a test for arsenic. Suspected victims were exhumed and Scattergood conducted toxicological analyses of the remains of four individuals between 26 July and 16 October 1872, all of whom were proved to have been poisoned by arsenic. He began by analysing the viscera of the first victim he received, 7-year-old Charles Edward Cotton, but in the later cases he also analysed the soil in which the bodies had been buried. Organs examined from the bodies included the stomach, bowels, liver, heart, lung, spleen and kidney. As well as her step-children Cotton was also suspected of poisoning her former lover and lodger Joseph Nattrass. Scattergood undertook a microscopic analysis of the contents of Nattrass’s intestinal canal, confirming the presence of arsenic.

It is clear that the samples were brought to Scattergood by police sergeant Thomas Hutchinson, who travelled to Leeds from County Durham, and Scattergood was careful to indicate chain of custody in his notes: the samples from various organs were actually received by someone called Lockwood —presumably an assistant, who locked them in his desk and took them out for Scattergood.[14] The press reported the case in depth, and the Illustrated Police News commended Hutchinson as “an intelligent officer … well adapted to fulfil the task assigned to him.”[15] He is shown in the bottom left-hand corner of the sketch in which Mrs Cotton takes centre stage, bearing the masculinized features expected of the Victorian murderess.[16] The reality was rather different, as the photograph on the right shows.

The West Auckland cases relating to Mary Ann Cotton occupy the next 27 pages of the notebook. In fact the first page of this lengthy toxicological investigation details the tests that Scattergood made on his reagents, to ensure their purity. What he did not include was information about where he obtained his chemicals — but perhaps we can assume that it was from the Leeds-based company Hirst and Brooke?

On 14 March 1873, a week after Mary Ann Cotton’s trial, conviction and death sentence, Scattergood followed up on a point made by her defence counsel, Mr Campbell Foster, that the arsenic in the bodies might have been due to arsenical wallpaper or accidental ingestion of a mixture of arsenic in soft soap (used for keeping insects at bay). Scattergood concluded that, regarding the wallpaper theory, “this would not account for the presence of solid AsO3 in the stomach”, while soft soap “could not possibly have been powdered any more than butter could have been powdered.”[17]

Mary Ann Cotton was executed at Durham Gaol on Monday 24 March 1873, five days after giving birth to her last child.

Conclusion

The forensic work that Scattergood did from the Yorkshire College raises many questions that cannot be answered before his notebooks have been fully transcribed and studied in detail — a project that we plan to undertake in the near future. We are particularly fascinated by the economics of forensic practice: the work took a lot of time and must have cost a considerable amount in reagents, so how much did Scattergood charge? Were farmers paying him to analyse dead animals so that they could make claims against insurance policies? How innovatory was Scattergood in his analytical methods? He was clearly reading relevant scientific literature and using up to date methods but he published almost nothing during the course of his career. Despite his lack of publications Scattergood was not unknown. The variety of people who contacted him for help, and the prosecution lawyers that called upon him to appear in court, were aware of his reputation as an expert. Consequently, he was involved in some of the major criminal cases of the day. Scattergood’s notebooks have the potential to tell us much about the networks of people involved in crime investigation in the nineteenth century, scientific and medical expertise outside of the capital, and the economics and logistics of undertaking this kind of forensic research. As a regional forensic expert, it is time that Thomas Scattergood takes his place in the historiography of crime and forensic practice in England: there is clearly more research to be done.

Laura Sellers is a historian of medicine, psychiatry and crime in the nineteenth century. She has recently finished her PhD on medicine, psychiatry and sciences of criminals in English nineteenth-century convict prisons. She is currently a short-term Fellow at the Leeds Humanities Research Institute.

Images

Main image: Dr Thomas Scattergood (First Dean of Medicine, Yorkshire College 1884-1900) by Sir George Reid, c. 1899-1900, oil on canvas. Reproduced by permission of the Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery, University of Leeds.

Map of England: R. Wilkinson, The British Isles, 1812. Downloaded from A Vision of Britain under a Creative Commons Public License.

Map of urban centres (1861) and rail lines (1854): Robert M. Schwartz, “Railways and population change in industrializing England: an introduction to Historical GIS”, Department of History, Mount Holyoke College, 1999.

The West Auckland Poisoning Case, Illustrated Police News, 16 Nov 1872, 1. Retrieved from the British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk) and reproduced by permission. Image © The British Library Board. All rights reserved.

Mary Ann Cotton (31 Oct 1832 – 24 Mar 1873), c. 1870 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Strychnine acetate, crystallized in tufts of needles: William A. Guy, Principles of Forensic Medicine, 2nd edn (London: Henry Renshaw, 1861), 494.

References

[1] “Thomas Scattergood, M.R.C.S., L.S.A.”, The British Medical Journal, 3 Mar 1900, 547.

[2] “Thomas Scattergood, M.R.C.S. Eng., L.S.A.”, The Lancet, 10 Mar 1900, 737-738; M.A. Green, “Dr Scattergood’s case books: a 19th century medico-legal record”, The Practitioner 211 (1973), 679-684.

[3] Katherine D. Watson, “Medical and chemical expertise in English trials for criminal poisoning, 1750–1914”, Medical History 50 (2006), 386.

[4] Brotherton Library, MS 534/Vol.2, 157-158.

[5] Brotherton Library, MS 534/Vol.1, 131-133; Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 20 Feb 1869, 10.

[6] There is an account of the trial in The Liverpool Mercury, 24 July 1897, 5 but this is not the article that Scattergood pasted in to his notebook.

[7] Ian Burney, Poison, Detection, and the Victorian Imagination (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006), 116-151.

[8] Brotherton Library, MS 534/Vol.1, 1-3.

[9] The case file is in The National Archives, Kew: DURH 18/2, Regina v. Pearson, 1875.

[10] Brotherton Library, MS 534/Vol.2, 4-10.

[11] Brotherton Library, MS 534/Vol.1, 79-84.

[12] Brotherton Library, MS 534/Vol.1, 81.

[13] William A. Guy, Principles of Forensic Medicine, 2nd edn (London: Henry Renshaw, 1861), 494.

[14] Brotherton Library, MS 534/Vol.1, 179-206.

[15] Illustrated Police News, 16 Nov 1872, 2.

[16] Judith Dorothea Rowbotham, “Gendering protest: delineating the boundaries of acceptable everyday violence in nineteenth-century Britain”, European Review of History 20 (2013), 945-966.

[17] Brotherton Library, MS 534/Vol.1, 188.

Share this: