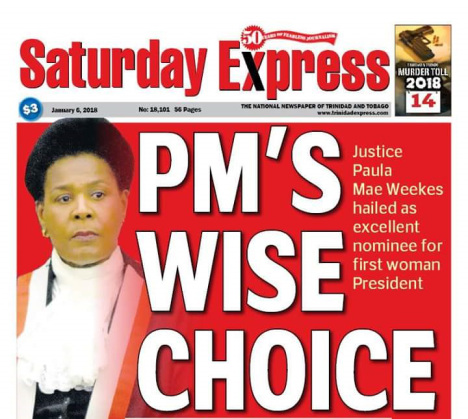

Sir Ellis Clarke, Noor Hassanali, ANR Robinson, Prof George Maxwell Richards, Anthony Carmona; these are the names of the 5 individuals who have had the honour of sitting atop the state apparatus over the past 41+ years, with Justice Paula Mae Weeks on the verge of joining the short and lofty list as number 6.

The recent passing of Prof Richards on 8th January brought up familiar recurring questions vis-à-vis the usefulness of the post of president in a country whose British-derived political system places executive power in the hands of the head of government (i.e. the prime minister), with the president playing a mere ceremonial role akin to the one played by the British monarch in the UK and the 15 other Commonwealth realms where she is head of state.

Here in the former British Caribbean, Trinidad and Tobago isn’t the only republic as both Dominica and Guyana are republics and thus have presidents. However, while Dominica also mimics the Downing Street – Buckingham Palace setup with a president of the same status as T&T’s, Guyana’s is an executive president.

So why is it that T&T has equipped / saddled – depending on who you ask – itself with a president who doesn’t wield political power, isn’t chosen by the electorate and who by dint of this may, according to some, be thought of more as the appendix than the heart or brain of the body politic?

Prior to the president, there was the Governor-General:

Per the Report on the Trinidad and Tobago Independence Conference 1962 obtained courtesy the TT National Archives, The People’s National Movement general council moved in January 1962 that Trinidad and Tobago not participate in what would be left of the Federal experiment in the wake of the Jamaican withdrawal, and move forward along the path to independence.

The British Secretary of State for the Colonies concurred and set up an Independence Conference with a view to hammering out a constitution for an independent Trinidad and Tobago.

A draft was produced for public feedback in T&T in April 1962, and the Conference convened on several occasions in London over the following 2 months culminating on 8 June 1962.

The 31st August independence date was set first and foremost. Decisions and parameters on joining the Commonwealth, human rights, citizenship, parliament, electoral issues and the branches of government were laid out.

Item 3 of the Conference’s conclusions dealt with the office of Governor-General as follows:

The Governor-General will be appointed by the Queen and will hold office during her pleasure. Provisions will be made for the Governor-General’s functions to be performed by such person as Her Majesty may appoint when the office of Governor-General is vacant or the holder of the office is absent from Trinidad and Tobago.

The Governor-General was meant to be an apolitical arbitrator like the British monarch in the UK.

Being neutral and free from partisan influence, the Governor-General was the guarantor of the maintaining of

“the spirit of democracy, of friendliness between all sections of this country”

As it was put by Hon. C. A. Thomasos, Speaker of Trinidad and Tobago House of Representatives, on the occasion of a 1964 courtesy call by a British parliamentary delegation (1).

****

Of Empire and butter:

In 1976 T&T traded in the Governor-General for a ceremonial president when the 14-year-old country opted to become a republic within the Commonwealth, just as India had become the first to do in February 1948, some 6 months after gaining independence from Britain.

When India made what was at that point a bold political statement, remaining within the Commonwealth post-colonial club while shedding allegiance to the British monarchy, then South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts quipped that

“If we spread the butter of the British Association until it is too thin it will disappear”

Anyway, the point being made here is that countries of the unwinding British Empire were evolving but still maintaining ostensible links with Britain and the British political way.

Becoming a republic in 1976 but setting up a president who functioned like the monarchy in Britain was Trinidad and Tobago’s way of doing itself what India did when, in the words of its independence leader Nehru

“without restricting our freedom, India may form some sort of link with the Commonwealth which will benefit and enable us to contribute to the peace of the world”.

The ceremonial president, coupled with continued membership in the Commonwealth were the “some sort of link” retained by T&T with its erstwhile political heritage.

A President – British blueprint but a local architect

At the 1932 West Indian Conference held to shed light on the future of the troubled region gripped by poverty and social upheaval and only just coming into a sense of self, regional leaders including Adams, Bird, Marryshow and N Manley declared that

“the West Indies must be West Indian”

And that

“The destiny of the West Indies was now moving into West Indian hands.”

It took another 3 decades for this to really come to fruition with the start of decolonisation in 1962, and Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana and Dominica each went a step further than the rest towards moving their destiny into local hands as opposed to ones selected by the Queen of England. No more Queen-in-Council or Governor-General-in-Council for us, thank you very much.

****

Going back to the British parliamentary delegation courtesy call previously mentioned, a few excerpts of what was communicated by the head of the delegation Sir Kenneth Thompson (MP) are relevant to the issue at hand:

- The president as a product of democracy & parent of the nation:

“if parliamentary rule is the true child of democracy, […] it is also the parent and guardian of the rights of the people […].”

As a defining facet of T&T’s parliamentary system, being assumedly above politics, and following this quote, the president is at the same time a product of democracy – he isn’t voted for by the public but is still voted for by their parliamentary representatives – and the gatekeeper of that democracy. Democracy brings he / she to the position, then he / she uses the position to safeguard the very same democracy in a sort of self-sustaining system.

- A president for all:

Sir Kenneth spoke of the importance of people who are

“drawn from the Government and the Opposition […], but […] represent neither Government nor Opposition nor political party.”

Having

“a higher and more responsible duty [..] as servants of the House.”

This aptly sums up what the president of Trinidad and Tobago is supposed to embody.

- The president & Rousseau’s volonté générale :

“Parliamentary democracy, we know, may wear other forms from the one we recognise, but no form will satisfy or survive unless it mirrors the opinions and the feelings of the masses who must endure its rules and obey its laws. […].”

The general will (la volonté générale in French) is, according to French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, what citizens recognise as beneficial for them and society as a whole. The fact that there is not sustained and generalised outcry from various quarters within society for a change to an executive president seems to signify that the general will of the people is to have the system function as is.

As such the present iteration of parliamentary democracy complete with a ceremonial president survives because it mirrors the opinions and feelings of the masses who are subject to its authority.

Can / should the system change? The jury is out.

*FIN*

(1) Source: Trinidad and Tobago Information Bulletin, January 1964.

Advertisements Share this: