★★★

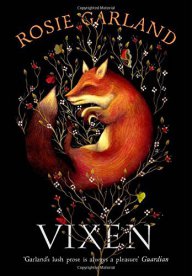

This was on my library wishlist even before I read Rosie Garland’s Night Brother, and without knowing a thing about it. I was just intrigued by the title and tantalised by the cover: I thought it might be a bit like Emma Geen’s Many Selves of Katherine North, but of course I was thinking too literally. Set in the Devon village of Braunton in the plague year of 1349, it in fact tells the story of Thomas, the village priest; Anne, his housekeeper and would-be wife; and the strange, mute girl who is discovered half-drowned in a bog after a terrible storm. As Death draws its wings close around Braunton, these three find themselves at the heart of a struggle between small-mindedness and broad vision, played out in microcosm in the kitchen and barn of Thomas’s meagre home.

At the age of fifteen, Anne is ready to make something of herself. Inspired by the success of her best friend Margret, who has become ‘wife’ to the priest in a nearby village, she sets her cap at the village’s new cleric, Thomas of Upcote. Anne is sure that, if she becomes his housekeeper, it’ll only be a matter of time before she’s found her way into his heart and into his bed. But she’s disappointed. Thomas is a self-centred, pious bore, whose notion of humility blends into miserliness. More to the point, he sees Woman as a creature lying in wait to snatch him off the road to salvation. Resented by his parishioners, who remember the jolly former priest, Thomas is aware, deep in his heart, that he’s failing. He needs a miracle to prove to everyone how holy he is – and he finds it, to his amazement, in the girl-child rescued after the storm. He hopes that, by taking her in, he’ll give Anne something to keep her busy, and he becomes increasingly convinced that this wild creature has been sent by God, as a blessing on Thomas and his work.

The girl brought into this unhappy house has no name. The villagers come to call her Vixen, for her wildness; Anne calls her the Maid. We start the story in her head, and so we know that – mute or not – she isn’t the simpleton everyone takes her for. The girl is resolutely fleeing westward, outpacing the spread of the great plague, knowing that Death is hot on her heels but trusting in her own wits to keep her at bay. Her time among the villagers is unplanned, but the girl needs food, warmth, clothing and money, and if she has to play along with the priest’s fool notions of a miracle, she’s willing to do it. The only hitch in her plan is Anne: kind, gentle Anne, who cares for the girl more than anyone else has ever done, and begins to crack open her carapace.

It’s a book of contrasts: common sense against tradition; freedom against captivity; male against female; hidebound ritual against a flexibility of thought, being and deed. Garland writes well, and conjures up the soul-crushing misery of life in a small medieval village. Life depends on the harvest, which can be wiped out by storm or rot; the people toil all year long, with holy days and saints’ feasts offering the only chance for a rest and merriment; and their lives are governed by the personality and preferences of the current priest. She captures the intoxication of religious belief and the desperate thirst for miracles of any kind, in a world devoid of all its certainties. The combination of the wild girl and the priest and the attempts to bring her closer to God reminded me, of course, of the excellent Knowledge of Angels, but Garland doesn’t come as close to philosophy. Nor does she have the same compassionate depth of characterisation.

The main problem for me in this novel was Thomas. He’s petty and pusillanimous. To be unlikeable is no crime in itself, but I felt that he was unpleasant without being all that three-dimensional. We have no real sense of how he came to be here – save for a brief flashback to a miserable childhood, apparently prompted by a desire to quickly add some backstory. Desperate to reel in his congregation with one hand, he pushes them away with the other, selfish and sanctimonious, rarely getting beyond one-note harping on his position as a Man of God. Although Garland hints that he does feel something for Anne, these words always sit a bit strangely in his mouth, as though they’ve been put there by the author rather than proceeding from his own volition (yes, I know they were, but it shouldn’t feel like that). I think the story would have been stronger if he were that bit more sympathetic, less prone to parroting the same lines over and over again. His foolishness and petty ignorance are reflected back in the more knowing cruelty of the examiners he brings into the village. This means that at times the story becomes a rather simplistic ‘four legs good, two legs bad’ division, between credulous, foolish, tyrannical men and wise, caring, passionate women.

Garland is obviously fascinated by the way we can shift between different roles and personalities in our lives. Her main characters take this to extremes, and her concepts interest me, although I’m yet to be completely swept away by one of her books. Nevertheless, don’t be dissuaded by my comments: this is a perfectly good historical novel to delve into, full of the gritty realities of 14th-century life, and with an intriguing trickster at its heart, in the shape of our titular Vixen.

Buy the book

Share this: