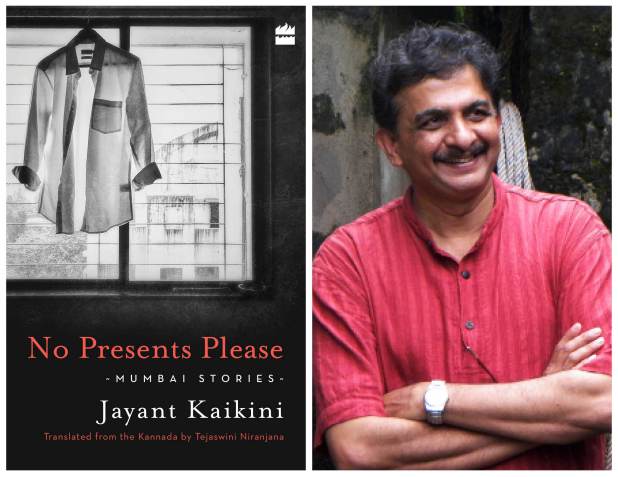

HarperCollins India’s latest anthology of short-fiction, out in November 2017, titled No Presents Please: Mumbai Stories is not about what Mumbai is, but what it enables. Here is a city where two young people decide to elope and then start nursing dreams of different futures, where film posters start talking to each other, where epiphanies are found in keychains and thermos-flasks. From Irani cafes to chawls, old cinema houses to reform homes, Jayant Kaikini, one of the stalwarts of Kannada literature, seeks out and illuminates moments of existential anxiety and of tenderness. As the four-time winner of Karnataka Sahitya Akademi Prize describes in this anthology, cracks in the curtains of the ordinary open up to possibilities that might not have existed, but for this city where the surreal meets the everyday.

The following quote by Jerry Pinto sums up our thoughts about the book perfectly:

‘Jayant Kaikini’s compassionate gaze takes in the people in the corners of the city, the young woman yearning for love, the certified virgin who must be married off again, the older woman and her medicines; Tejaswini Niranjana’s translations bring the rhythms of Kannada into English with admirable efficiency. This is a Bombay book, a Mumbai book, a Momoi book, a Mhamai book, and it is not to be missed.’

Here’s a story, ‘Water’, about Mumbai’s date with a cloudburst in July 2006. In fact, strike that. It’s perhaps the story of any typically rainy Mumbai day.

Water

‘We will be landing at Mumbai Airport in approximately twenty minutes. Please fasten your seatbelts.’

Chandrahas felt that the plane was shaking a little more than usual. He looked over his reading glasses at the skies outside. By this time, he should have been able to see Khandala, Matheran, Karla and Lohagad through a thin curtain of clouds. By this time, he should have been remembering some picnic, some trek, some trip or training camp he had been to in the mountains below with fondness. The Karla waterfall, which had once frightened his friends and him during the monsoon, should be visible from here like a small metal badge. But he could see nothing except a thick wall of cloud. And the aircraft was swinging alarmingly from side to side. Chandrahas wondered if the plane could land under these conditions. He looked around at his fellow passengers with a small face as the plane gave a jolt, and the voice announced: ‘We apologize for the turbulence caused by inclement weather. Please return to your seats and keep your seatbelts fastened.’ Like a passenger in the last seat of a bus that had just gone over a pothole, the elderly man seated next to Chandrahas said, ‘My goodness.’ Chandrahas gave the man’s hand a squeeze and smiled at him reassuringly.

In the last one and half hours, the two had spoken more than was perhaps necessary, and now an artificial silence prevailed. The man’s name was Santoshan. He was a Malayali who had lived all over India, and had spent the last thirty years in Ahmedabad establishing his own factory. Now, for the past two years he had been living with his only daughter in Bangalore. He hadn’t been well of late, and he regularly came to Mumbai to consult with a famous doctor. Normally his daughter or his son-in-law accompanied him. Today, the son-in- law had got delayed, and was going to be on the next flight. Not wanting to trouble the old man with the tired voice, Chandrahas said, ‘You’ll certainly get well soon. I can see it from your eyes.’

Smiling, the old man said, ‘Tell me the truth and I will believe you. I never used to trust anyone when I was in business. Only believed in money. But after I fell sick, I’ve started believing anything anyone says.’

Santoshan, though, did not seem to want to know anything about his neighbour. Feeling awkward, Chandrahas offered: ‘I’m from Honnavar, on the west coast of Karnataka. I’ve been working in Mumbai for the past ten years. I’ve had an interview for a better job in Bangalore. They even paid for my travel. I’ll get twice my present salary. It’s as though I’ve already got the job. But now I don’t know what to do.’

‘Relax, man,’ said Santoshan. ‘Stay wherever you can work well. And everything else will take care of itself. Whether it’s Timbuktu or Miami or Mumbai, or anywhere else on earth, if you get the right atmosphere and you can lose yourself in your work, it’s like you’re serving your own country and your town. And if you stay in your own state or town and remain lazy or corrupt or wicked, that’s the biggest betrayal.’

Wishing Chandrahas well, the old man dropped off to sleep, and had woken only now, when the plane was jolted by the storm. Chandrahas guessed that he must be worrying about his son-in-law joining him and how the rains might disrupt their schedules. ‘Don’t worry,’ he said. The air hostesses were moving up and down the aisle checking to see whether all the passengers had fastened their seat belts. ‘Whenever there’s turbulence, I look at the faces of the air hostesses. If they look normal, fine. But if they look as though they’re trying to hide something, then we can expect the worst. But look, this one is smiling…’

Santoshan gestured with his head. The noise from the aircraft increased, and it began its descent. Everyone held their breath as the plane plunged down and finally thudded onto the runway. As if mocking their fearful journey, Mumbai Airport stood glowing in the bright afternoon sun as though under a spotlight. The passengers jostled each other in their hurry to get off the plane. Santoshan tried to move aside for Chandrahas to alight. But Chandrahas said, ‘I’m not in a hurry, sir. If you like, I’ll stay with you until your son-in-law arrives.’

‘Really?’ asked the old man, pausing. Then he went on: ‘Do me a favour then. I doubt that the next flight will arrive on time in this weather. Instead of waiting for my son-in-law, I should go straight to the hospital. My appointment is at 3 p.m. If it’s on your way, you could drop me there and carry on.’

‘Certainly,’ said Chandrahas.

‘An autorickshaw will do,’ said Santoshan, but Chandrahas hailed a taxi and they both got in. The passing vehicles were gleaming wetly, as though the airport was the only spot where it wasn’t raining.

‘Whatever you might think, sir, once one has stayed in Mumbai for a while, and one comes back after a journey, there’s a strange sense of security. Look at the taxi and auto chaps here, they always return your change, however little it is. There’s something that welds us all together here,’ said Chandrahas, as he pulled his water bottle out of his bag and gave it to Santoshan, asking him to drink. As the old man guzzled, the veins in his neck shone palely. Seeing the brown radiation burn marks on his neck, Chandrahas mentally wished the man a quick recovery.

‘You’re quite right. I too wanted to set up my business in Mumbai, and I even stayed here for some time. But the girl I lost my heart to was from Ahmedabad, and she wasn’t ready to leave that town. Like in that story about the king who went on a hunt and heard the voice of a bird, and for its sake acquired the branch, the tree, the grove, and the entire region, and he set up his kingdom there and never went home.’ Santoshan spoke to the taxi driver, asking him, ‘And you, my man, have you ever been in love?’

The driver laughed, ‘Parvadta nahi, saab, can’t afford it.’ Encouraged by his passengers’ conversation, he went on: ‘Money flows like water in Mumbai, saab. Some see it, some don’t. Those who see it grab it by the handful, and travel by taxi. Those who don’t, become taxi drivers.’

‘No, no,’ said Chandrahas, ‘there are also people like me who see the money but can’t get hold of it.’

The taxi driver, who said his name was Kunjbihari, pointed to the sky, which now looked like a black wall. ‘Woh dekho saab, a lot of water will fall today, bahut paani girne wala hai,’ he said.

Chandrahas was always amused by the Mumbai idiom that referred to rain as ‘water falling’. He thought of the Holi festivities when someone in the apartment above would throw buckets of coloured water on the revellers below. As the taxi climbed onto the flyover after Santacruz, the skies darkened even more. ‘See, Kunjbihari, plenty of money is collecting in the sky,’ said Santoshan.

Asking the driver to wait outside Hinduja Hospital, Chandrahas went in with Santoshan to meet Dr Dastur, the specialist. Not heeding Santoshan’s protests, Chandrahas insisted on waiting with him. He phoned his wife Sarayu, who worked in an office at Churchgate, and told her, ‘It looks like it’s going to rain very heavily. You should leave office early. I’ll be home in a couple of hours … Yes, I know, we have to pay our loan instalment today. Let’s do it tomorrow, please. It doesn’t matter … I don’t know, I think I’ve got the job … Yes, yes, I’ve told them I’ll need to be given a house … No, we need to decide now. I’m finding it difficult … Sarayu, you tell me what to do. How long can we struggle here just because we like the city?’ He hung up after whispering goodbye.

Santoshan thumped him on the back and said, ‘Good, do as she says.’

Just then, Santoshan’s name was called. He picked up his file and asked Chandrahas whether he would accompany him. After examining the old man behind a drawn curtain, Dr Dastur proclaimed, ‘Excellent, Mr Santoshan. You’re doing very well. The treatment from your doctor in Bangalore seems to be okay. Maybe you need to finish another cycle of radiotherapy, but you can do that there. Why didn’t your daughter come? How is she? How is the school that she’s running?’ As he spoke, the doctor wrote out the details of his examination on his letterhead.

Then for the first time, Chandrahas saw a deep helplessness in Santoshan’s demeanour. The old man, dragging his voice out from deep down, said, ‘Doctor saab…’

‘Yes, what is it?’ asked the doctor as he kept on writing.

‘Nothing really, just that next April my granddaughter might get married – it is being planned right now.’

‘My God … You have a granddaughter about to be married? Unbelievable! Well, I’ll see if I can find a seminar to go to in Bangalore, and be sure to attend the wedding.’

‘So kind of you, Doctor. But that’s not what I meant…’

‘Then?’

‘It’s only another six months. Somehow you must keep me alive until then.’

‘No, no! You’ll live a hundred years.’

‘I’m sure you tell everyone that. You seem like god when you say that. I want to do nothing else but keep looking at you. But I know what’s happening with me…’

Just then, Santoshan’s son-in-law called. His flight had not yet left Bangalore. ‘Don’t worry, I’m with the doctor. I will call you later,’ Santoshan said, cutting the call short.

‘Doctor, please … stretch my life till April. I’ve promised my granddaughter that I’ll be there for her wedding. Please try…’

Dr Dastur gently slapped him as though in anger. ‘What rubbish! You’ll move on only when you’ve seen your granddaughter’s daughter.’ He looked at Chandrahas as though to seek his approval.

Chandrahas felt a cloud pass over his heart. ‘I’ll wait outside,’ he said, slipping away. It sounded like a tenant pleading with his landlord to let him stay for another six months. Santoshan’s request was intense in its simplicity. Rows and rows of people sat outside, waiting their turn, waiting to make their request. A few months for some, a few days for the others…

Then he saw Kunjbihari, the taxi driver, running towards him with some urgency, shouting, ‘Saab … the rain’s falling at a tremendous pace! You should leave now, or none of us will get home today. The local trains are slowing down. I hear there’s water on the tracks at Sion and Kurla. The traffic is slowing down too. If you need to stay here any longer, I’ll leave.’ He was as alert as an animal which has heard the approach of impending disaster.

Chandrahas reassured him: ‘No, we’ll just be a minute. Where will this chacha go in this weather? Let’s drop him wherever he wants to go.’ Chandrahas went inside, and Kunjbihari ran out, finessing the strategy through which he would pull his car out of the maze of honking vehicles.

By the time the taxi came to the main road, day had prematurely turned to night, and water was falling in thick sheets from the skies. The roads were full of vehicles trying to get to the distant suburbs. ‘Oh, what mazaa this Mumbai rain is!’ exclaimed Santoshan.

‘Fun? What are you saying? Now you’ll see mazaa,’ Kunjbihari drawled, rubbing his forearms as though he were preparing for battle. Throwing the taxi into little lanes and alleys, he began to take them towards Mahim Creek.

‘You can drop me anywhere. I have friends at Bandra Bandstand. They’d come and fetch me,’ said Santoshan. ‘No one will come,’ said Kunjbihari. ‘Everyone is stuck somewhere. Like us. Look at this … we’re khalaas, finished!’ He beat his forehead and pointed to the jam on the Mahim– Bandra flyover. Vehicles were stuck to each other like thousands of ants, showing no sign of movement. In the deafening and blinding rain, the city itself appeared to be melting away. From their vantage point on the bridge, Kunjbihari’s passengers could see the local trains below, at a standstill on the flooded tracks. Some of the braver passengers had jumped into the waist-high water and seemed to be swimming hither and thither. People had alighted from stationary buses and were trudging on foot towards their destinations.

‘In another hour, the rain will stop and everything will be fine.’

‘In another two hours, the police will set right the traffic.’

Chandrahas was tired of saying these words again and again. Over the taxi’s FM radio, they were hearing news of how the entire city had come to a standstill. There were also messages from people to their families, to their children, to their friends, relayed by the radio station:

‘Where are you?’

‘You must stay back in the office.’

‘I’ll go to my maami’s place.’

‘I’m fine.’

‘I’ll stay on the station platform.’

By this time, water had filled the electric grids and the telephone control boxes, and the city’s phone lines fell silent. Chandrahas tried to call Sarayu several times from his mobile but failed. Maybe she was still at her office. Maybe she was at Churchgate Station in a train compartment. Maybe she was walking through waterlogged streets. Thinking of this made him more silent.

‘Don’t worry,’ said Santoshan. ‘She is sure to be safe.’ As he spoke, he realized that his son-in-law wasn’t going to be able to reach him. ‘Kunjbihari, do one thing. Drop me back at the airport. I have a return ticket. I’ll just take whatever flight I can get.’

‘We can’t go anywhere without the traffic moving, saab,’ said the driver, getting out of the taxi and splashing ahead in the water to see what was happening.

Now night started mingling with the darkness of the rain. The phalanx of rainwater poured down as if to mix up all the colours of old images. Even those travellers who had fifteen or twenty kilometres to go were getting off stranded buses into the water, and slowly a mass of people began to move around the vehicles. Everywhere in the city, the water was rising swiftly. The same clouds that had shaken our aircraft in the afternoon are now breaking into pieces, thought Chandrahas. Then the clouds had seemed like a battalion of tanks ranged for war. Chandrahas wondered what kind of turbulence this heedless rain was evoking in the poor old man who wanted just another six months on this earth.

‘Sir, shall I get us something to eat? Keep listening to the radio, I’ll be back soon,’ said Chandrahas as he got out of the taxi and walked towards the Mahim market. There was a curious spirit in the crowds that walked along, soaked with rain. Some were whooping and shouting. They were calling out to those still in vehicles, heckling them:

‘This bus won’t move today.’

‘The entire highway is under water.’

‘Mahim Creek is flooding.’

‘The sea water is getting into the low-lying areas.’

‘The ground floors of all the houses in Kalanagar have been flooded.’

As the crowd muttered to itself, these bits of information spread to everyone in the city. Schoolchildren in their uniforms in the pouring rain, with soaking schoolbags, walked like small, bent mountaineers in the darkness. Where did they live? How would they get there? When would they reach? Shopkeepers were calling out to the children and handing them biscuits, bread and bananas. People in the area were asking the children to come into their homes and wait out the rain. Neighbouring chawls and apartments were opening their doors to the women and children getting off buses. Chandrahas bought chips and some bananas and strode back to the taxi through the water. Santoshan had just finished talking to Kunjbihari. ‘There’s a traffic jam until Borivali, saab. And all the vehicles trying to take short cuts through the suburbs have caused an even bigger jam. The water is too high to recede quickly. Or else I would have told you to start walking. You could have reached the airport in an hour, and at least got some shelter over your heads. But no, my Basanti’s your only refuge today.’

‘Basanti?’

‘My taxi’s name, saab.’

‘Where’s your house, Kunjbihari?’

‘Not a house, saab. Just a kholi – in Oshiwara. My wife and children are in UP. Only if I drive a taxi here will they be able to light a fire in the house.’

Suddenly Santoshan asked, ‘Kunjbhai, does life seem to you like hell or like heaven?’

‘What a time to ask this question, saab!’ said Kunjbihari. ‘But look, how people are enjoying themselves even at this time – as though this was a fairground. Well, everything depends on how we think about it. If I think I’m happy, it’s happy I am. If I think I’m sad, then I’m sad. Isn’t that so, saab?’

As if to say how simple and right the driver’s philosophy was, Santoshan raised his eyebrows at Chandrahas. Kunjbihari went on, ‘As someone said – it’s better to be happy in hell than unhappy in heaven.’ He settled down to eat a banana.

On the radio, they could hear that all forms of transport – planes, trains, buses – had been cancelled. There were also these announcements:

‘For Pankaj, Shweta and Nobin who are stuck at Dadar TT, this special song … Kajra Re!’

‘On the request of Jyoti Patel and her friends stuck in a train between Ghatkopar and Vidyavihar stations for the past six hours, we’re playing Dil Chahta Hai.’

Thus, even under pressure the city was sharing its songs. ‘Amma, I’m staying at my aunt’s house in Shivaji Park. Don’t worry about me, I’ll come home tomorrow. But don’t get angry with me – my school bag fell into a drain near Portuguese Church.’ When they heard this boy’s message, Santoshan breathed the word ‘Amma’.

Something seemed to affect Chandrahas, who swallowed hard and then began to speak: ‘Sir, I must share this story with you. A couple, our close family friends, had two lovely children. Suddenly, three years ago, the husband died of an illness. The widow was trying hard to raise the children, but just four months ago her daughter died in an accident. Now she’s completely shattered. She thinks everyone she loves is likely to leave her. She’s afraid that if she loves her eight-year-old son too much, he’ll go away too. So she’s always cold and rude to him. One day this child says to her, “Amma, since Pepsi is supposed to have pesticide in it, why don’t you and I slowly drink two large bottles of it and kill ourselves?” How can an eight-year-old kid think of committing suicide? How can we reduce their pain, sir? Why should they experience such suffering?’

It was past midnight. Throughout the city, the vehicles had come to a standstill. Those who were in buses and trains went to sleep in their seats. Those in offices, shops and kiosks, dozed where they sat. Those who had started walking, found that they couldn’t go any further, or couldn’t go back to their starting point either. Hotels kept their shutters open, allowing passers-by to come inside and sleep. Sardarjis had set up langars wherever possible, and served dal and roti to those who were stranded on the street. But the city’s feet were still submerged in water.

Kunjbihari awoke. Opening the door on Santoshan’s side, he said, ‘Chacha, let’s go.’ Half asleep, the old man slowly got out of the car, and limped along because his feet had gone to sleep. Chandrahas followed them. In this strange, wet night with its intoxicating mixture of sleep and wakefulness, of water, light, fear, journeying and weariness, they walked as though in a dream. Between them was the feeling of an intimate fatigue, as if they had known each other for a long time. Guiding them through a few small gullies, Kunjbihari brought them to a tumbledown dwelling that seemed half-drowned in the water. A few children were trying to remove whatever water they could with buckets. The cot, a chair and cupboards were submerged. Standing in the middle of all this, a woman was slapping rotis onto a pan. On various nails hung the possessions of the house – a cloth bag, an umbrella, a clock and a sari or two.

‘Kaanchubehen, I’m Kunjbihari, a friend of Hasmukh Ali, who’s a friend of your husband Pyaremohan’s. I’ve never visited you all before. Today, when the entire city’s gone phut, we got stuck by Mahim Creek.’

‘Please sit down. Have some roti,’ said the woman, giving them each a plate with two rotis. They stood in the water and ate in that uncanny silence. The woman’s children held out cups of water to them. Chandrahas could not drink it. Santoshan gazed at his cup as if meditating, and then drank the water slowly sip by sip. Chandrahas felt both anxiety and surprise. As they thanked the woman and took their leave, Chandrahas whispered, ‘Should we give them something?’ ‘No, no,’ said Kunjbihari. ‘Hasmukh Ali would kill me.’ ‘Kaanchubehen,’ Kunjbihari addressed their host. ‘You husband was near Colaba this morning around 10 a.m. There’s not much flooding there. I’m sure he’s been getting customers that side. Tomorrow, when the water goes down, he’ll come home. Don’t worry about him.’ Before they walked away, Kunjbihari quietly slipped some money into the children’s pockets.

When they got back to Basanti in the midst of thousands of stalled vehicles, the rain was still coming down. Some volunteers were directing the walkers: ‘Go this way. Milan Subway is under water. And all the drains are open. Try to walk only on the roads.’ Others were handing bread and fruit to those stuck in their cars. Piercing through the stillness of the night, a train standing in the water would suddenly let out a whistle. Chandrahas felt very thirsty and couldn’t fall asleep. He went to a small grocery shop nearby. Almost everything was sold out. Chandrahas saw a crate of twelve bottles of Bisleri water. When Chandrahas asked the white-haired shopkeeper for water, he was handed one bottle.

‘We’re two of us,’ said Chandrahas. ‘One has to go back to Bangalore. We don’t know how long we’re going to be stuck here. Why don’t you sell me the entire crate? I’ll give you double.’

The shopkeeper laughed sadly. ‘Do you think you’re the only one stuck on the road? Can’t you see? Women, children, old people – they’re all stuck. This is all I have. You’re a young man and look quite fit. Take just one bottle, and take one more for your friend. Is this a time to make money? Here, give me twenty rupees. That’s the printed price.’

Chandrahas was filled with shame. Handing over the money, he took the two bottles and returned to the taxi.

They sat for a long time in silence. Much after midnight, when the sound of human beings diminished, the men in the taxi felt as though they were hearing the waves of the sea, which wasn’t far. Around the streetlights, one could see the drops of rain falling. Kunjbihari said, ‘Don’t worry, sir. I’ll pray that you get well soon. You’ll certainly be there for your granddaughter’s wedding. This is my dua for you this night.’

Santoshan squeezed the driver’s shoulder, saying, ‘You know why I got this sickness? I was one of the first in this country to sell water. In the 1970s, I was the first to bottle water and sell it. My mind was telling me not to, but I did it all the same. You said earlier that money flows like hidden water, but I sold the water that was before my eyes. The happiness you get from doing what’s right is nothing compared to the unhappiness of doing something even while knowing it’s wrong. That’s a sin. That’s why I’ve fallen sick. It’s my body punishing me for not listening to myself. I now have to experience this – there’s no way out.’

As Santoshan stared out of the window, an orange thrown by a volunteer fell into his lap, and he held it with both hands, laughing, like a kid taking a catch. ‘Kunjbhai, the rotis you got us today and the water we drank are the tastiest things I’ve eaten in my entire life. It was like amrit.’

Old Hindi film songs wafted from the FM radio stations as did more messages. Every now and then, Santoshan kept stroking Chandrahas’s hand saying, ‘Don’t worry about Sarayu. She must have paid the loan instalment and got onto the local train. She’ll be fine, wherever she is. There can’t be a safer time than this.’

‘Yes, sir, there isn’t a safer place than this right now. This city never lets go of your hand. As Sarayu said, I’ll continue in my present job and stay in Bombay.’ Kunjbhai turned down the radio volume and tried to sleep with his head on the steering wheel. Suddenly, they heard a weird voice. A man pushing along a small bicycle was shouting, ‘Amitabh Bhaiyya zindabad, Amitabh Bhaiyya amar rahe, long live.’ Behind him were a dozen people also pushing cycles, flying colourful flags. They carried bags, a small bucket and a few other things tied to their cycles, giving the impression that they were on a long journey. Chandrahas and Kunjbihari got out of the vehicle and waited for the procession to go past. In the dead of night, in those waterlogged and weary streets, the man’s followers kept proclaiming the heroic journey’s purpose.

‘Our Gagan Bhaiyya has come all the way from Allahabad. He’s a born fan of Amitabh Bachchan. When he heard that his hero’s health is not good, he took a vow so that Bachchanji can get well again. Because of that vow, he’s brought water from the Ganga–Yamuna sangam, bringing it all the way on a bicycle. We believe that if a person drinks this water he’ll be cured of all ailments. But look at this magic! We bring the water all the way on a cycle for thousands of kilometres, and the moment we reach this city the skies break open! What a good omen. Move aside, let us pass! Amitabh Bhaiyya zindabad, long live! Amitabh Bhaiyya amar rahe!’ On Gagan Bhaiyya’s face there was supreme joy. The sangam water swished around in his little vessel. The movements of his limbs contained the swirl of this water. Kunjbihari called out, ‘Gagan Bhaiyya, go straight and turn left at Khar, and then go straight to Juhu. That’s where Amitabh Bhaiyya’s house is. Jai ho.’

As the little vessel of sangam water brought for Gagan Bhaiyya’s hero went past in the last hour of the night, in this street filled with deep silence after this flood that had marooned lakhs of homes and lakhs of people, Santoshan felt he was witnessing a humble object becoming divine. He said to Chandrahas, ‘Come in and sleep a little. We’ve already spent fourteen hours here. Don’t know how much longer it’ll be.’

As Chandrahas sat in the car he said to the driver, ‘Kunjbhai, you too should go to sleep. Good night.’

Kunjbihari began to laugh. ‘Good night? It’s good morning already. Dekho.’ Slowly, it was becoming light. The pre-dawn glow from the east shone on the thousands of vehicles backed up on the road, giving the illusion that they might start moving any time.

No Presents Please is published in paperback by Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins India. Originally written in Kannada by Jayant Kaikini and translated into English by Tejaswini Niranjana. Now available in bookstores.

Share this: