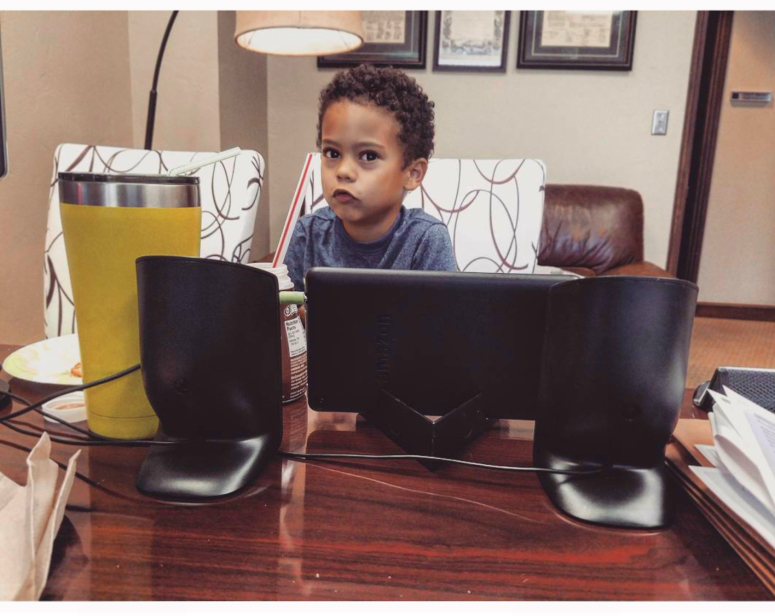

My little man came to work with me today. He had his tonsils and adenoids removed last week and is still “recovering.” His throat is still a little sore, but for the most part he’s been himself. However, he has a couple more days until he’s cleared for play in regular society, so he came to the office with Dad.

I remember those rare times, back in the day, when I went to my Dad’s office. Those trips were just shy of magic to me because they were tiny glimpses into this other, mysterious world my dad voyaged to and from each day.

See my mom’s occupation, like my wife’s, was fairly easy for a my young mind to comprehend. Patients came to her when they didn’t feel good, and she, in turn, would make them feel better. From my perspective, that was also what she did at home, so Mom was always out being Mom. That, I could get my head around.

Dad’s career was a little less tangible. There were digits, numbers, codes, paperwork, etc. It was confusing. All I really knew was that he worked at the bank downtown with the popcorn machine in the lobby. That ambiguity made each of the trips more intriguing. But getting to see what he “did for a living” wasn’t what always stood out to me. The thing about trips to Dad’s office was the totality of the experience.

It started with the drive through downtown to the bank that’s been there since 1901. It continued with Mom’s audible exacerbation or exuberance about her parking options, and getting to use the “employees only” entrances. Then there was swiping watermelon flavored suckers from the tellers, a peppermint from a desk in the pit, and of course, that popcorn machine I told you about. All the while, everyone I passed would greet me with a huge smile, a high five, or tell me a joke. They all seemed to know who I was and who I had come to see.

With each trip, a tiny spark was lit, shining just enough light to see that whatever it is Dad does, he must be pretty important. To see that the people who spend their day with him find him special enough to treat me like an heir to some kind of royalty. As if just being his kid meant I too could be just as special.

It was these moments that began creating context for where Dad was always rushing off to in a suit and tie every morning and why he was often the last to get home. He was important in the world outside of just my house, and he had responsibilities to take care of. He was at home with me as much as he could be, and I developed better framework for where he was and what he was doing when he couldn’t.

The more I got to visit him, where he was, in his other habitat, the more I felt I understood what he does “out there,” and the less I felt concern about when he would get home or when he might leave again.

He wasn’t away, I was sharing him.

Did I ever truly understand what his job was at a young age? Probably not. I’m not sure I fully tried. Once I developed a concept that made sense to my young mind, I became satisfied. The narrative those visits allowed me to construct was comforting.

True, complete, or not…

I get the sense that this impulse, this need to construct frameworks and handy little boxes for the unknown, is natural, and that I am not the only person that did this with one or both of his parents. I also think that this impulse for comfort over truth extends itself to all other areas of our lives, particularly in the realm of the spiritual, even if in less obvious ways.

One way it shows up is in the common emphasis on the requirement of certainty and knowledge when it comes to our religious dogmas, our interpretation of the Bible, and the ability and courage to defend the same.

“Getting it right,” and being able to prove it against any and all comers.

I come from a tradition, similar to many of you, where successfully defending any and every aspect of our faith is essentially tantamount to having faith in the first place.

A tradition:

Where it is easy to find ourselves more concerned with proving we are right (or at least that we would give no quarter to the opposition’s point of view) than actually being right.

Where it becomes easy to believe our ‘correct thinking’ about God is evident in our bank accounts, career options, test scores, and the outcomes of sporting events.

Where it becomes easy to believe our answered prayers come by way of our diet, abstentionism, voting records, legalism, tithe percentages and heterosexuality.

A tradition where it becomes easy to be fooled.

“Being right” has proven to be a difficult definition to nail down in the first place when discussing ultimate questions of human existence and purpose. Let’s not forget that, at times, the majority of Christians have been certain about the Bible’s affirming stances on issues ranging from geocentricity, polygamy, and slavery, to the innate spiritual limitations of women and subhuman status of people of color.

Certain, but wrong.

Still, we continue to demand a single homogenous system be culled from a collection of texts as diverse in message and viewpoint as the books of the Bible. We see this diversity as a diversion from, and incompatibility with, the pursuit of faith and truth instead of considering the likelihood that this diversity may be indispensable to it.

But is this because such thinking is actually true or just more comfortable? Peter Enns, in The Sin of Certainty, wrote that:

The preoccupation with holding on to correct thinking with a tightly closed fist is not a sign of strong faith. It hinders the life of faith because we are simply acting on a deep unnamed human fear of losing the sense of familiarity and predictability that our thoughts about God give us.

Our thoughts about God, are not God.

I know that may sound obvious, but if we take a moment of reflection, and are honest with ourselves, we often confuse and combine the two without so much as a second thought.

Look at it this way: I would not consider it stepping too far out on a limb to say that the majority of people who subscribe to the Christian Religion believe they, or at the very least, the churches to which they attend, have “figured it out.” Whatever interpretation of the Bible and its contents our local spiritual community professes, is the Truth the Whole Truth and Nothing But. Often this goes unsaid, and even unknown, until someone from the outside presents a challenge. Yet how quickly an honest and simple question can trigger our defenses – our need to plant our flags, put our feet down, and reign condemnation, if necessary, instead of engaging in a simple discussion

Can’t you see the problem? Your church isn’t the only one that is certain. At the very least there are the three big branches: Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant. Protestants are split up into Adventists, Anglicans, Baptists, Calvinist (reformed), Episcopalian, Lutheran, Methodist, Pentecostal, Presbyterian, so forth and so on. I could stop there, but it would be overly simplistic, I mean, I’m sure I left someone off this list that’s offended already. Not to mention each of the above are umbrella terms for even more; there’s at least two Baptist branches down here (but blame Wikipedia)!

All told, according to the Center for the Study of Global Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary (which is what popped up in Google, I’ve never heard of it) there are approximately 41,000 Christian denominations and organizations in the world. Forty-One-Thousand!

Now that probably includes a whole bunch of weird things in it, so okay, I’ll tone it down. But still, that’s just the Christian churches- The New Testament crowd. We also share some commonalities in the Old Testament with Judaism and Islam, at least, and each of those trees have multiple branches as well. Then you have all the other world Religions that are not “Abrahamic.” They are interpreting or experiencing something.

But just sticking to the Bible crew for now, each group is technically differentiated by how certain they are about some biblical aspect that the “rest of us” have ignored, devalued, missed or dismissed. Each believes they have the answers (more, if not all). Each believes and claims to know “THE Truth,” and their proximity to that truth aligns them closest to the One True God.

My point is, that is a whole lot of variance in “truths” for the One True God. Perhaps Truth is bigger than we think! Perhaps Grace is greater as well!

We are all using the same book with the same history (outside of the fact that the book itself has gone through many translations and was compiled throughout time drawing influence from multiple cultures, languages, and writing styles). We interpret this same collection. We all ask the same questions. We all have different answers.

What does that mean?

Does that mean it’s one church versus the rest? Us vs. them?

Are we all wrong? Are we all right?

Are we going to be alright!?

That’s the real catch right? What terrifying questions. What a burden uncertainty seems to be.

We cannot stand uncertainty, even though we are surrounded by it. If and when we forget where we stored it away and uncertainty bubbles to the surface, it is often met with a chorus of voices concerned we are losing our faith, our motivations, and our souls.

This anxiety causes us to forget uncertainty is evidenced by our biblical heroes. Jacob wrestled with God to become Israel. The authors of Ecclesiastes, Job, and Lamentations constantly express their uncertainties. Thomas had doubts as did eye witnesses to a resurrected Jesus. Paul and James disagree on the purpose of good works.

Yet, when we encounter moments of uncertainty, we feel obligated to cauterise them before the infection spreads. We seek concrete definitions and lines drawn in the sand as early as possible to feel safe. We lock these ideas of who and what God is, what He does, and what the Bible means in a vault and never allow these concepts to be touched or removed.

I believe that there is a problem with selling such certainty because the ultimate focus is the self, not the Divine. Ultimately, this serves as a salve for fear. If I pick a church’s ethos and am fully certain about the “steps”, then follow those steps, there’s nothing for me to worry about. A + B = C.

Should information present itself as some threat to our mathematical certainty, we have a guttural tendency to vigorously ignore, debate, and disprove that information. Additionally, it is equally as important that those around us believe that we know what we are talking about and that we are completely right. Otherwise we will feel less certain about our souls’ fates. Less certain of our destinations when we die. Again, with the behavior modification for after-life insurance.

Every time we win a spiritual debate or argument “for the Lord”, or even if we lose but never waiver or give an inch, no matter how inarticulate, ridiculous, or hypocritical or even NON-Christ like we appear in that moment, or in our reasoning, we have paid our premium for the month. We have met our deductible. We took a stand! “Now you better hold up your end of the deal when I kick it Jesus!”

But the purpose of even discussing the Divine should be for growth, compassion, love, and interconnection between the people speaking. We should be embracing debate, conversation, growth and progression of thought. We should appreciate the value of a foreign perspective and how it can help shape our own. We should be wrestling with the Mysteries. We should be striving toward a constantly evolving understanding of God as He or it, or whatever, continuously expresses itself to its creation, through its creation. We should not limit the Divine to simply learning how to behave, or blindly accepting what has become comforting on “faith.”

I place quotations around the word “faith” there due to another Peter Enns quote:

Believing that we are right about God helps give us a sense of order in an otherwise messy world. So when we are confronted with the possibility of being wrong, that kind of “faith” becomes all about finding ways to hold on with everything we’ve got to be right. – We are not actually trusting God at that moment, we are trusting ourselves and disguising it as trust in God.

Perhaps though, we are less concerned with discovering God and too preoccupied with categorizing Him. We keep Him in our boxes because we understand them not because He fits. We are more comfortable with the unknowable if it can become predictable. We relegate the Divine to the confines of the narratives we have created and placed on It, like clay shaping the potter. These narratives give us peace of mind. They are comforting.

True, complete, or not…

Perhaps we are like me at that young age, wandering the halls of First National Bank, looking for my dad’s office. Perhaps we are just children trying to develop stories about our Father to better explain those moments in life when we can’t feel Him, know what He’s doing, or know when He’ll come back again. Maybe sometimes finding Truth is not as much our goal as comforting our insecurities, satisfying our fragile egos, or justifying our own sacrifices.

I am not necessarily saying this instinct is “wrong.” I’m not speaking to correctness. I’m speaking to the biases in and true purposes of this “correctness.” I’m asking:

What if these narratives about God are more about calming anxiety about our mortality than understanding something greater about the source of life?

What if our need for certainty is really about making God predictable?

What if “Faith” is not that simple?

Maybe, just like kids wandering the halls, what Dad is really doing here is beyond us, too complex for simple words, or in some instances, simply unknowable.

What I can say for sure is this: if the people that spend time with Him, treat the rest of us like heirs to His royalty, we can all come to a deeper understanding of His stature and importance.

Just a thought…

I Corinthians 13:8-10 & 12-13:

Love never dies. Inspired speech will be over some day; praying in tongues will end; understanding will reach its limit. We know only a portion of the truth, and what we say about God is always incomplete. But when the Complete arrives, our incompletes will be canceled.

We don’t yet see things clearly. We’re squinting in a fog, peering through a mist.

But for right now, until that completeness, we have three things to do to lead us toward that consummation: Trust steadily in God, hope unswervingly, love extravagantly. And the best of the three is love.

Share this: