Today I am delighted to welcome Anthony Cartwright, author of The Cut, to my blog. In this guest post he talks of the Black Country where he grew up and where The Cut is set (you may read my review of the book here).

“I have lived half my life here, half in London, felt the chasm between the places widen further and further.”

The Cut was commissioned by Peirene Press

“to build a fictional bridge between the Britains that opposed each other on referendum day.”

It is a fabulous read.

The EU funded some of the work you look out on now, just by the house where my uncle used to live, here on a terrace elevated above the Birmingham Road traffic. You used to be able to look into the old football ground from the upstairs bedrooms. Beyond that was the County Ground, where in summers gone my great-grandad would sit in his deckchair behind the bowler’s arm, out of the wind, with a pint of mild. He could look at the castle on the hill, listen to the clang of metal being bashed. The people loved Tom Graveney, Basil D’Oliveira, the Headleys; sons of England and Cape Town and Jamaica and Dudley. The town is an enclave of Worcestershire within Staffordshire; hence the cricket. The earth opened one morning in the eighties and the sports grounds fell into a hole. With a shift in the old limestone workings below, the place was swallowed, went the same way as the jobs. When the hole was filled years later they built a cinema, hotel, gym, bars, called the place Castle Gate. It looks like the rest of England. Or England looks like Dudley.

The newspaper says that Brexit threatens the new light railway set to run up the hill from the mainline, says the new Aldi will bring over thirty jobs. The town, like every place you look out on from this view, voted for Brexit, two to one for Leave across the West Midlands. Map the regions that made the difference and it follows the pattern of the death of industry, of coal, iron and steel.

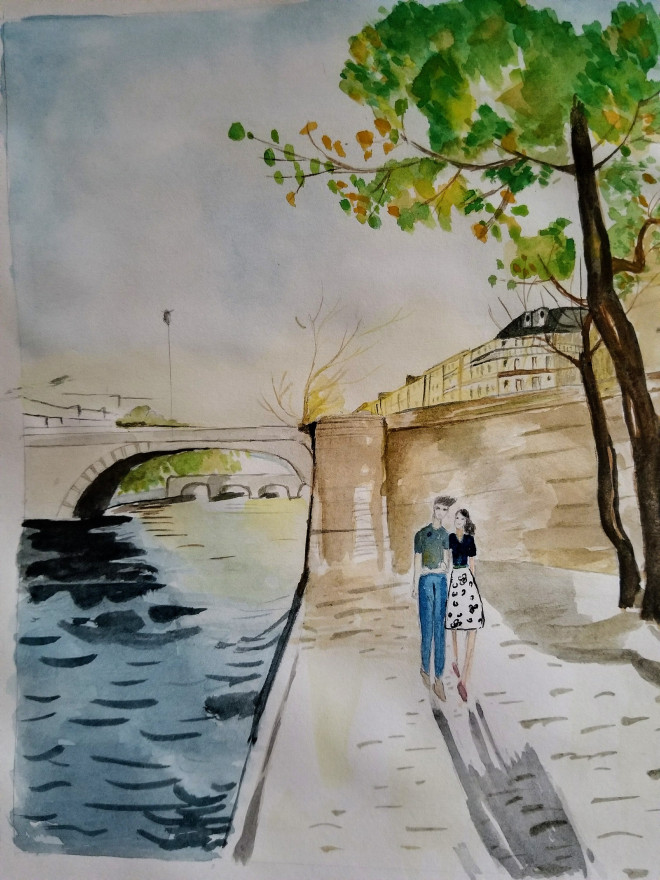

The ground is always unsteady here. Take a step and an abyss can open up, a foot in one half of the country, a foot in the other half, the chasm widening below you. The cut, the canals, more relics of an old industrial order, were the things that linked the land-locked midlands to the sea, to far-flung London. There used to be a pub called The Sailor’s Return on the crest of the wave of Kates Hill, as if a ship might sail from the distant Indies right into Dudley Port, and the sailor swagger homeward up Bunn’s Lane.

That we lived on an old sea-bed in the middle of England was one of the many wonders of growing up here. At the Wren’s Nest there are trilobites buried in the rocks, creatures from that prehistoric ocean, a symbol of Dudley, hard and strange. The trilobite is there on the coat of arms, just above the salamander, who basks in flames below. We are a country of symbols, with our new Black Country flag – red, white and black – a link of chain emblazoned across it. Black Country Day is 14 July, the day the Cobb’s engine house started pumping water from the mines at Windmill End. The industrial revolution will be permanent.

Except just not here, any more. I remember the day I first thought I might become a novelist. Sitting on the 120 bus somewhere between the Langley Maltings and the Albright & Wilson chemical works, waiting to climb the hill, I thought I might write about this postage stamp of land, like Faulkner said, about defeat, about what it’s like to come down on the far side of something, about the past never really being past.

There is a whole shadow country beneath our feet. The canal tunnels pierce the hill and there are great caverns under the castle. There was a plan, early in the Second World War, to move the whole of the BSA munitions works here, to make an underground city of twelve thousand people and a few hundred thousand guns. It didn’t happen, but this is a country of outlandish plans. Lubetkin built the zoo in the thirties, white modernist pavilions set in old quarries. See the flamingos now from the top deck of the bus to West Bromwich. There is a hole in the hill where they used to dump the dead animals, a well of strange bones. The Richardson brothers, local Thatcherite property men, once planned the world’s tallest building at Merry Hill, the shopping centre they built by the old Round Oak steelworks, unstable ground indeed, where thousands of jobs fell into a hole and disappeared.

Wind down the lanes through Gornal, where the trees bend to each other above the road, to The Crooked House, another pub, a place made crazy with subsidence, where you can watch a marble roll uphill. This is a country of signs and wonders. And it is perhaps so unlike the country that is portrayed – if it is portrayed at all – in newspapers and on television screens and on radio stations that speak with an accent you do not hear on these hills, that you might struggle to picture it at all.

Which is where I should begin. This novel will be a story about magical thinking, a story about loss. The vote was a piece of magical thinking, a vote about loss. And it was many other things as well. Cast the zoo bones, read the runes on tunnel walls. If I must fall into this void then you will come too. There are countries where you have never been, though you have lived in them all your life.

‘It doesn’t matter what the question was, the answer was no,’ a friend says to me when we talk about the vote. And he goes on to tell me about someone he knows who killed himself not long ago, a couple of kids and no one saw it coming, and we talk about the people we know who have done similar. But try not to draw conclusions. There are people doing just fine. And it’s not like the place has a monopoly on the sense that the future lies somewhere in the past.

Watch the traffic flow along Birmingham Road past European roadside flowers. It was my uncle’s funeral a few weeks ago. Our family, living and dead, form a web across these hills. My brother, though he usually drinks Guinness, likes a cocktail at Frankie and Benny’s on Castle Gate, not far from where our great-grandad sat. They raise their glasses across the gulf of years. I have lived half my life here, half in London, felt the chasm between the places widen further and further. Out of the tunnel and into the light, down the hill and into the stream, along the river and into the sea.

And back again. We are all connected.

This is where to begin.

Anthony Cartwright is a novelist from Dudley. He is the author of four previous novels, most recently Iron Towns (2016). The Cut is the second novel in the Peirene Now! series, and was published on 23 June 2017.

Advertisements Share this: