Download links for: De kleine filosoof : wat het kinderbrein ons vertelt over waarheid, liefde en de zin van het leven

Reviews (see all)

Write review

Interesting info. Helped make me less afraid of adopting an older child from foster care system....

Fascinating study of the infant mind, charmingly written.

Excellent book for anyone who teaches or has children.

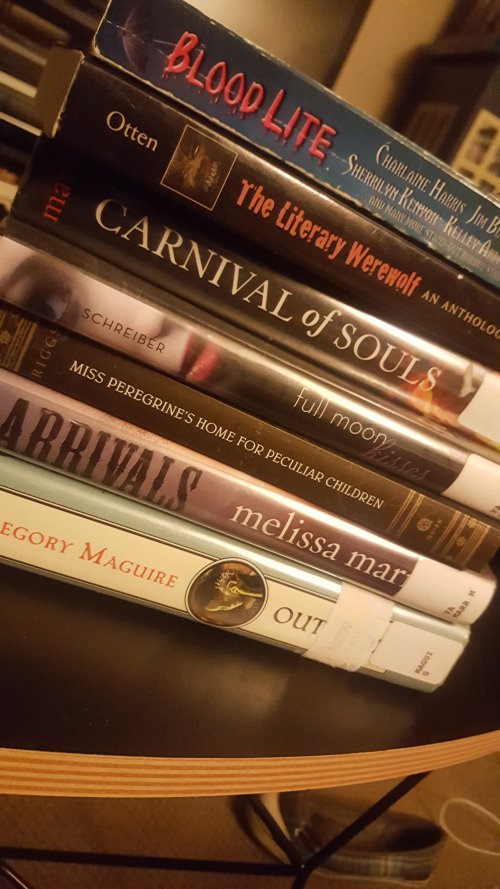

Other books by Middle Grade & Children's

Other books by Alison Gopnik

Related articles