Margaret Atwood recently published this op-ed, opining her view that the left’s increasing extremism has led to a foregone conclusion: men accused of sexual misconduct are always guilty. Worse, she claims, we are replacing the legal system with vigilanteism because we no longer have faith in its efficacy. The example Atwood offers up as supposed proof of the left’s rabid distaste for due process is the case of Steven Galloway, the former chair of the department of creative writing at the University of British Columbia. She wrote:

“In November of 2016, I signed – as a matter of principle, as I have signed many petitions – an Open Letter called UBC Accountable, which calls for holding the University of British Columbia accountable for its failed process in its treatment of one of its former employees, Steven Galloway […]. Specifically, several years ago, the university went public in national media before there was an inquiry, and even before the accused was allowed to know the details of the accusation. Before he could find them out, he had to sign a confidentiality agreement. The public – including me – was left with the impression that this man was a violent serial rapist, and everyone was free to attack him publicly, since under the agreement he had signed, he couldn’t say anything to defend himself. A barrage of invective followed.

But then, after an inquiry by a judge that went on for months, with multiple witnesses and interviews, the judge said there had been no sexual assault, according to a statement released by Mr. Galloway through his lawyer. The employee got fired anyway. Everyone was surprised, including me. His faculty association launched a grievance, which is continuing, and until it is over, the public still cannot have access to the judge’s report or her reasoning from the evidence presented. The not-guilty verdict displeased some people. They continued to attack.”

With so many sidestepping the legal system, she asks, what kind of justice will materialize in its stead? The answer, for the moment at least, is #MeToo. The movement’s tactics range from the sharing of personal stories of trauma to the outing and public shaming of known sexual predators. Amazingly, this has led to the removal of these men from their positions of power or other dire consequences.

Atwood notably wrote the classic dystopian novel The Handmaid’s Tale in which women are stripped of their rights and forced to adhere to a patriarchal caste system after a totalitarian regime successfully overthrows the US government. It might strike some as odd, then, that she would fashion this straw man argument falsely concluding where #MeToo is headed (and clearly, she is not alone by the looks of the media landscape). The example of Galloway is neither typical nor does she acknowledge that to be the case, thereby lending her more-credible-than-most voice to the sea of others decrying #MeToo as dangerous, unsexy, man-hating, silly, or whatever else.

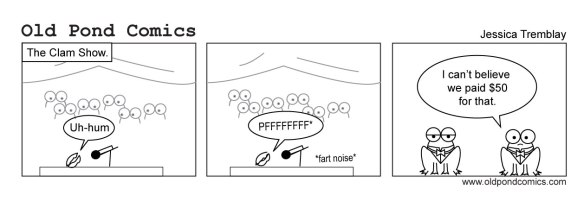

Case in point: this hilarious satire from the Washington Post adopts the voice of the imperious, self-righteous #MeToo critic:

“When we were only coming for people who had actually done bad things and, indeed, admitted as much, it was fine. But now we are going into bars and scooping up any men who have done anything, be it ever so slight: a smile, a look, forcing a woman to live under his desk in a secret room and refusing to tell her what year it is, offenses of WILDLY DIFFERENT DEGREES that I am just lumping together as though I think all of them might be possibly acceptable if you did them outside the office.

First they came for men I did not like, some of whom had beards that did not look good, others of whom were conservative media personalities, and still others of whom combined those characteristics. But then it started to spread until we were even ruining the careers of people who were accused of minor offenses, like saying “good morning” with a weird emphasis, or eating a sandwich while maintaining eye contact with someone who wasn’t their wife, or emailing a woman a respectful compliment.

Oh no, have none of these things happened? My mistake. I am worried that they will, which is just as bad.

My point is, there is a spectrum. There are some things that are not as bad as other things — yet these feminists don’t agree! There is no distinction made. (That is, there have been distinctions made, but this could cease at any moment.)”

Not only is #MeToo blown off as a “witch hunt,” but it is routinely accused of being founded on both the presumption of men’s guilt and hyperbolic, bloated charges of sexual assault. Atwood is in the latter camp, and for her, #MeToo is a problematic last resort measure brought to the fore by the broken legal system. She says:

In some ways, it’s true that #MeToo is a movement drummed up by sheer desperation, in part as a response to the pathetic legal recourse for sexual assault and sexual harassment victims. However, Atwood falls into fear mongering when she warns ominously of “new power brokers” usurping the role of the legal system if we keep using tools like #MeToo to root out sexual assault (and assaulters). This argument smacks of intellectual dishonesty and is far too simplistic, as sexual assault cannot adequately be addressed by legal reform alone. Furthermore, her likening of #MeToo and social media activism to vigilanteism recalls a time when it was even more shameful to speak out about sexual assault– a reminder that those matters are private affairs. The secrets victims carry, as #MeToo has pointed out, are awfully convenient for perpetrators. If speaking up is vigilanteism, but legal recourse is inadequate at best and violent at worst, then what are our options, exactly? While considering these questions, another star fell as if by divine intervention to provide some more analysis, if not actual answers. In the now infamous Babe article, a young woman only identified as “Grace” describes a brutish nightmare of a sexual encounter with comedian Aziz Ansari. There are already countless writers poring over the details of what happened, debating back and forth over whether what happened was really sexual assault or “just bad sex.” You see, Ansari didn’t technically do anything illegal, even though he repeatedly stuck his fingers down her throat, demanded oral sex even when she was distressed, tried to get her to have sex when she repeatedly said she didn’t want to, and other disturbing things. I’ve read some pretty shocking statements from various writers about how Ansari doesn’t seem like that bad of a guy. Manisha Krishnan from Vice said:“All too frequently, women and other sexual-abuse complainants couldn’t get a fair hearing through institutions – including corporate structures – so they used a new tool: the internet. Stars fell from the skies. This has been very effective, and has been seen as a massive wake-up call. But what next? The legal system can be fixed, or our society could dispose of it. Institutions, corporations and workplaces can houseclean, or they can expect more stars to fall, and also a lot of asteroids.”

I’m sorry, what? Aziz Ansari is no less than a self-styled feminist dating guru. He has literally written the book on the subject. He partakes in fluent, in-depth conversations about feminism, sexuality and consent. He has skewered sexual harassers in his comedy. HE. REALIZES. While we are at it, the narrative that men don’t know any better is false and harmful to well… everyone, really. So why is the “bumbling man” figure so pervasive? Simple:“[The encounter] suggests that he didn’t really give a shit whether she was having a good time or not. He was laser focused on getting laid. In terms of getting affirmative (enthusiastic) consent, he completely failed. I don’t necessarily think this makes Ansari a terrible person because I think it’s behaviour a lot of men probably don’t realize is awful.”

“There’s a reason for this plague of know-nothings: The bumbler’s perpetual amazement exonerates him. Incompetence is less damaging than malice. And men — particularly powerful men — use that loophole like corporations use off-shore accounts. The bumbler takes one of our culture’s most muscular myths — that men are clueless — and weaponizes it into an alibi. […] Men are every bit as sneaky and calculating and venomous as women are widely suspected to be. And the bumbler — the very figure that shelters them from this ugly truth — is the best and hardest proof. Breaking that alibi means dissecting that myth. The line on men has been that they’re the only gender qualified to hold important jobs and too incompetent to be responsible for their conduct. Men are great but transparent, the story goes: What you see is what you get. They lack guile.”Unsurprisingly, then, this whole poor, unwitting Aziz Ansari spin has absolutely worked in his favor. The Atlantic published an article— by a woman, of course, as the same piece written by a man would never see the light of day– calling “Grace” an irresponsible racist, weak for not fighting back or just leaving, and, it is implied, sexually promiscuous (so, perhaps, deserving of her fate?). Caitlin Flanagan, author of the hideously titled “The Humiliation of Aziz Ansari,” wrote:

“Was Grace frozen, terrified, stuck? No. She tells us that she wanted something from Ansari and that she was trying to figure out how to get it. She wanted affection, kindness, attention. Perhaps she hoped to maybe even become the famous man’s girlfriend. He wasn’t interested. What she felt afterward—rejected yet another time, by yet another man—was regret. And what she and the writer who told her story created was 3,000 words of revenge porn. The clinical detail in which the story is told is intended not to validate her account as much as it is to hurt and humiliate Ansari. Together, the two women may have destroyed Ansari’s career, which is now the punishment for every kind of male sexual misconduct, from the grotesque to the disappointing.”

It’s hard for me not to respond to this stunning example of internalized misogyny with strident anger, but I’ll try. There is no evidence whatsoever that Grace wanted anything from Ansari beyond basic human decency and consensual pleasure. She is the one who rejected him, not the other way around. Portraying her as a spiteful “woman scorned” is sickening, and the “clinical detail” provided should humiliate Ansari. What he did was despicable. Beyond that, “woke” dating is supposedly his area of expertise. What this woman Grace probably expected of Ansari, even more so than from the average man, was an understanding of compassion, communication, and feminist principles, as this is the way he markets himself, and quite successfully, as Flanagan herself points out. Flanagan’s ironically racist assertion that Grace’s account somehow flouts intersectionality and points an unjust finger at brown men absolutely flies in the face of women of color feminists doing work to unravel sexism in their own communities. It’s also pretty racist to assert that all men of color lack privilege. It is absolutely absurd to pretend that Grace is the more privileged of the two parties in this scenario, but that is exactly what Flanagan does. Aziz Ansari may not be white, but he is an older, wealthy celebrity, and he has been given the benefit of the doubt of because of his image as a lovable “woke bae.” Flanagan seems not at all to understand the meaning of intersectionality which shouldn’t really surprise anyone given the content of her flaming tire fire of an op-ed. It’s maddening that the normalcy of an encounter like this justifies its morality to many.

Legally, what could be done to protect women like Grace? We have seen the reactions from the public: She should have just left. She should have fought back. She could have screamed. Why did she go home with him? This happens all the time. It was just bad sex. Regret isn’t sexual assault.

Reactions like this to #MeToo were inevitable at some point precisely because the problems with rape culture are not merely legal in scope. Looking at this app created in the wake of #MeToo, we can see the absurdities revealed by legal thinking about sexual assault in its most reductive form. The app allows people to instantaneously and electronically “give consent” to sexual acts via legal and binding contracts. Although meant to be a helpful response to #MeToo, the app clearly misses the point of consent, which is that it must be ongoing. Instead, the app reads more like a sleazy way for “gray area” guys like Ansari to get away with their predatory behavior, seem woke, and yet still have the ability to act confused, ignorant or surprised later if there is a complaint. Legally, we can’t address nights like what happened between Ansari and Grace because of the inability of the law to interpret consent in a nuanced enough way. Furthermore, encounters like this are so common, they are nearly universal amongst young women (at least the ones I know, and this has been a common sentiment echoed in the media). Legal reform and proceedings have never been enough, and have never benefitted everyone. Reforms are only as good as they are implemented. Until they are able to address difference in meaningful ways and can contain the permutations of consent needed to fully address moral wrongdoing so many women experience in their sexual encounters, reforms cannot fully repair what is wrong with rape culture.

The proper response to the Ansari debacle isn’t, “this isn’t assault because it’s legal,” it is, “why is this is okay simply because it is legal?”

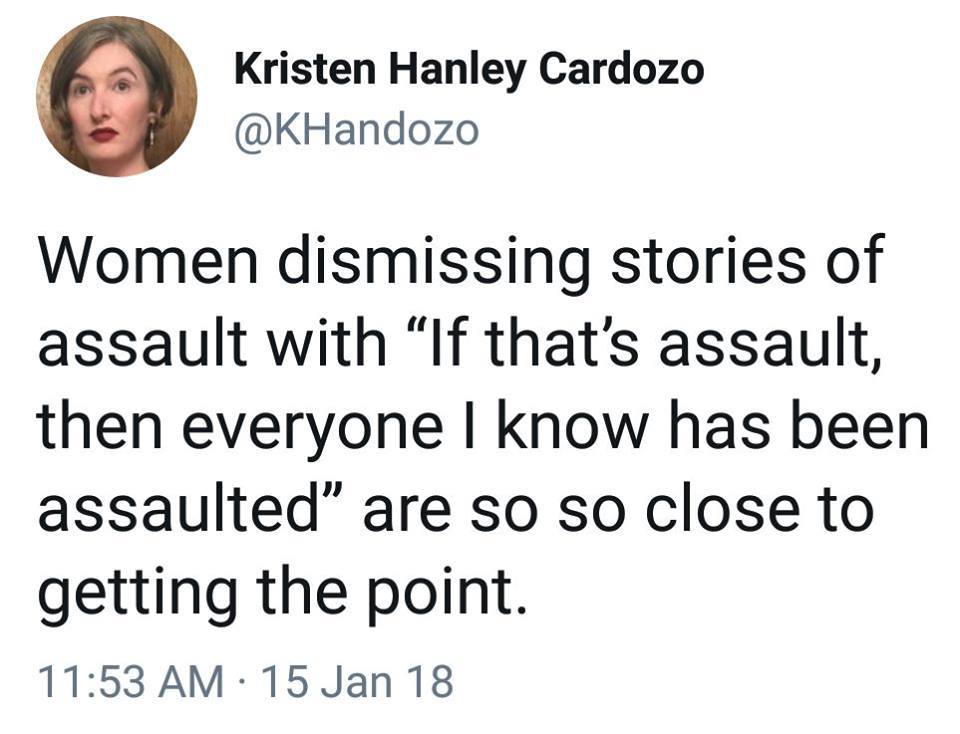

I leave you with this tweet from @KHandozo, who says it better than I could.