Earlier this fall I read two wonderful comic books in close succession, Liana Finck’s A Bintel Brief: Love and Longing in Old New York (2014) and Manuele Fior’s 5,000 km per Second (2009, translated 2016 by Jamie Richards, though the publisher does its best to bury this credit, hiding it in tiny print on the last page).

Artistically, they’re as different as could be, but they’re both beautiful. Thematically they didn’t at first seem to have anything in common, but paging through them again I start to see connections. Both are about dislocation and uncertainty, but one is much more confident than the other that these melancholy states can be overcome.

Finck’s book is named after a popular feature in the Yiddish newspaper Der Forverts (The Forward)—“bintel brief” means “a bunch of letters”—in which readers wrote in with their personal problems and ethical dilemmas. This early advice column became a mainstay of the paper, which began publishing from the late nineteenth century and continues today (though in much-reduced form). By the late 1920s, its daily circulation was 275,000, though its influence dwindled as Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe (shamefully) ground to a halt in the 1930s. Even without these government restrictions, however, the paper would have declined. For its task was paradoxical: the more it addressed the concerns of Jewish immigrants to America—the more it helped them work through the difficult process of assimilation in a new world—the more it prepared its own obsolescence.

Yet contrary to the story of Yiddish disappearance that’s been dominant for fifty years (leading to a contrary narrative that’s rapidly becoming just as clichéd, namely, that Yiddish isn’t dying), A Bintel Brief is an energizing, even joyful book. Which is amazing, because it’s filled with stories of despair, uncertainty, and pain.

At the beginning of the book, the narrator’s grandmother sends her a notebook, one the narrator had often noticed in her grandparents’ apartment when she visited as a kid. It’s a scrapbook of pages clipped from old newspapers. When she opens it, out steps a man (“old-fashioned,” “otherwordly”) who introduces himself as Abraham Cahan.

In real life, Cahan was a novelist and journalist who edited The Forward from 1903 to 1946. In the book he is an impish, wise, and excitable figure who rapidly falls in love with modern life. (After he gets a haircut, some new outfits, and a sharp pair of glasses he looks like any other Brooklyn hipster.) Eventually, after making the point about his own obsolescence as the editor of a paper written in a language most of its readers are learning to give up, Cahan disappears from the narrator’s life. But this turn of events doesn’t feel sad, since the book is about giving up the past—not heedlessly, but hopefully. It’s about being honest with yourself about who you are. And it’s about rejecting the guilt that comes from leaving anything behind.

The story of Cahan and the narrator frames the heart of book, which consists of sample letters sent to The Forward. Finck has condensed and edited them to fit the form of a comic book, but she’s been faithful to the spirit of the original. The letters are remarkable—heartfelt, passionate, disturbing, upsetting. Cahan’s responses are measured, firm, almost terse. A recently married woman complains about the many duplicate wedding gifts she and her husband have received (pillow after pillow, lamp after lamp), then worries that she is ungrateful. A barber dreams of slitting a customer’s throat after being insulted and then becomes so obsessed he’ll follow suit in real life that he can’t go to work. A cantor loses his belief in God and wonders whether he can continue in his profession—after all, he knows no other. A childless couple is offered a baby—the mother is penniless and young and can’t keep him—and can’t decide whether to adopt it, imagining all the things that could go wrong, even though they want a child more than anything.

Cahan agrees with the woman that a gift registry (though of course he doesn’t call it that) is entirely sensible and anything but rude: “Your ‘dream’ of having a decent life in America would be better classified as a ‘reasonable expectation.’” He exhorts the barber to “simply laugh off the dream and drive the whole matter out of his head.” He reminds the cantor that freethinkers and believers alike agree that “only a pious Jew may be a cantor” and for a nonbeliever to continue in the role would be “a shameful hypocrisy.” Yet he adds that many cantors have gone on to find work in the theater: “There may be other opportunities for you to make use of and honor your voice.” And he chides the couple for their “Hamletism”: “You should stop asking ‘to be, or not to be,’ and adopt the child immediately.”

Throughout, Cahan’s sympathy for the plight of new immigrants, all of whom are poor and oftentimes exploited, is apparent. To a woman who writes that she is convinced her friend and neighbour has stolen her watch, a precious gift from her son, which keeps the family from going hungry because she pawns it whenever they run out of money, Cahan writes, “What a picture of the wretchedness of the worker’s lot is to be found in this letter!”

These personal conflicts become even more powerful by being told through Finck’s arresting illustrations. The black and white drawings (interspersed with the occasional illustration in the pale blue of old airmail envelopes) express the past without being mannered or old-timey. Finck’s lines are often wispy (an artistic objective correlative for the Yiddish luftmensch, maybe?), but more powerful moments are usually rendered in a thicker, expressionist style. I’m not much good at describing drawings. Take a look at these examples instead:

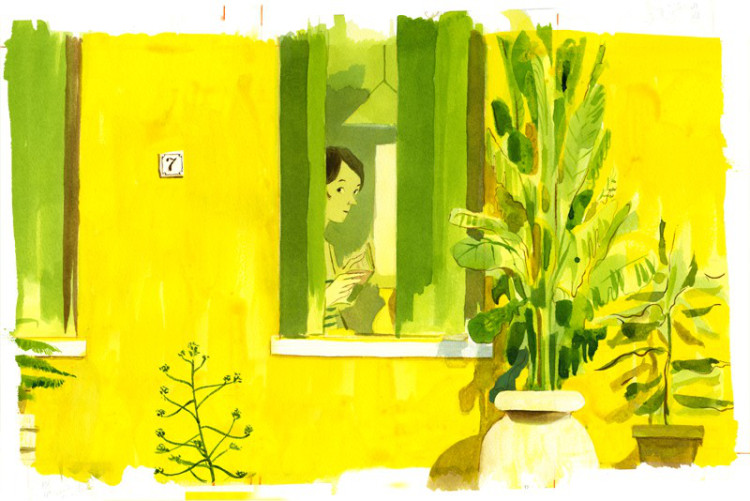

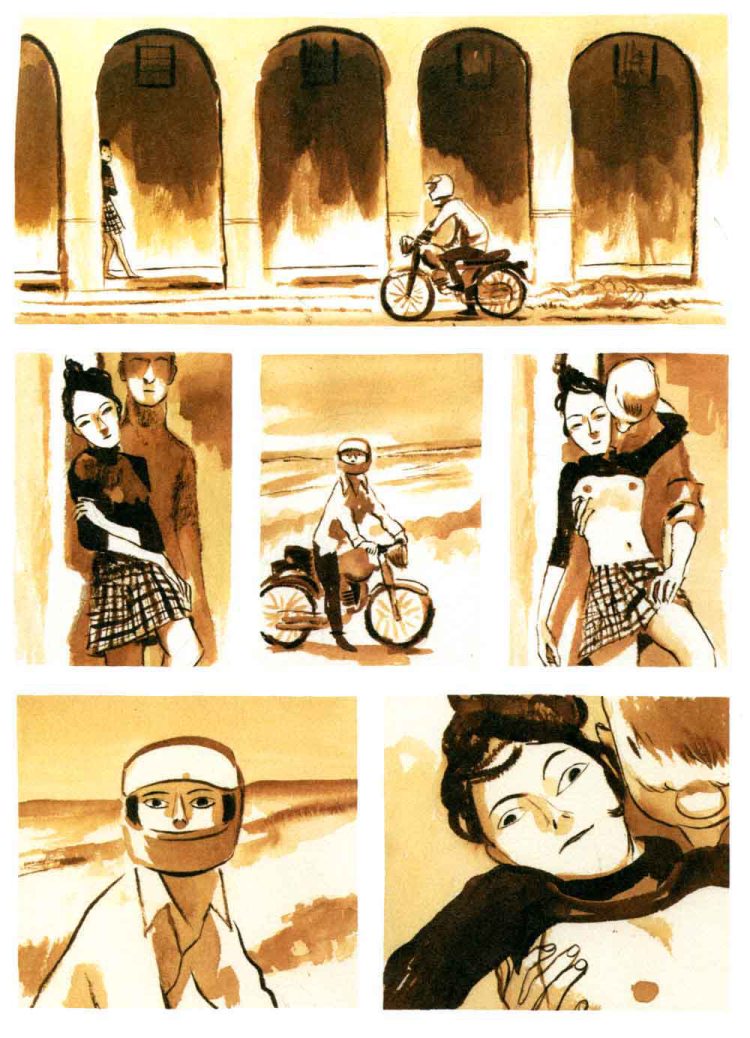

Although intelligently and carefully illustrated, words, as its title suggests, matter a lot in A Bintel Brief. That’s not true of 5,000 km per Second, which contains very few words, most of them from conversations that remain unfinished or at cross-purposes. The story is a love triangle, sort of. Piero is a shy, smart teenager with a garrulous, outlandish, confident, not very nice friend, Nicola, who makes fun of him in the guise of looking out for him. Yet Piero isn’t that nice. We see this in his relationship with Lucia, a girl who moves with her mother into Piero’s apartment building at the beginning of the book, and who he falls for. The not nice part doesn’t come until much later, though. At first he seems hard done by. For as soon as they get together, it seems, they separate. (I say “seems” because of Fior’s narrative structure and editing: each section of the book jumps forward in time without any exposition.) Piero travels to Egypt and Lucia to Norway. She writes him a letter breaking off their relationship—“without you I can breathe again”—and ends up with the son of her host family. Years later, pregnant with her first child, she reads about Piero’s work as part of an archaeological team in Egypt and calls him. (Their initially awkward but increasingly intimate conversation, pursued across a continent and despite the one-second lag in the phone call, gives the book its title.) Later, they meet up again back in Italy and get together for a drink. That evening, at first joyful and heartfelt, then increasingly maudlin and rueful, eventually becomes upsetting, even sinister. In a riveting scene, he follows her to the bathroom of the bar and locks the door. Their sex is consensual, probably, but a failure. Fior captures the indignity of middle-aged intimacy without disparaging that desire. In fact, since we see it as a product of all the ways that life seems to make choices for us, all the ways we become people we couldn’t have expected to become, we sympathize with it deeply—but we don’t romanticize it either.

Piero can’t get it up; Lucia tells him to take her home. In a central panel she repeats what she said at the beginning of their fumbling: “I told you not to look at me.” We can read this as her shame at herself, at the body she’s become. But we can also read it as a demand, almost a snarled rejection: leave me alone. After all, Piero is married with a child. His desire for Lucia after all this time seems driven more by anger and insecurity (he’s convinced things didn’t work out with Lucia because Nicola was always getting in the way) than by constancy and star-crossed love. In a final turn of events, our sympathy for Lucia is challenged. We’re left unsure whether there’s anyone to admire in the book, but a coda set in the early days of their teenage courtship reminds us of the joyful start of even relationships that turn bad for reasons that are too complicated to parse.

Fior’s drawings are sumptuous without being lovely (nothing twee about this book). Even when vibrant the colours have a sickly hue. Greenish yellows, browns and purples predominate. See what I mean?

I learned about this book from Shigekuni; be sure to read his compelling review.

It’s strange: although at first I liked Bintel a lot more than 5,000, the latter has stayed with me longer. Warmth is probably the quality that’s most important to me—definitely in people, and often in books. Finck’s book—so sympathetic to both those who need advice and those who give it—has warmth in spades. Fior’s book is not warm—not cold, exactly, but definitely unsparing, sometimes just this side of tawdry, though also keenly aware of what time does to people—but I keep thinking about it. That doesn’t mean it’s better. It just rattled me a little more.

Fortunately, reading isn’t a zero-sum game, so no need to choose. They can be read in an hour, but they’ll stay with you a lot longer. The best news is that Fink and Fior each have a new book out in English in 2018. I’ll be getting to them as soon as I can.