That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever lived, lived out their lives. The aggregate of all our joys and sufferings, thousands of confident religions, ideologies and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilizations, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every hopeful child, every mother and father, every inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every superstar, every supreme leader, every saint and sinner in the history of our species, lived there – on a mote of dust, suspended in a sunbeam.

–Carl Sagan

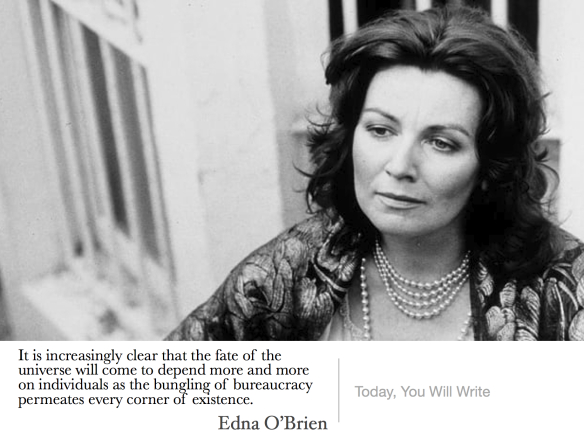

“Man is but a reed, the most feeble thing in nature, but he is a thinking reed. The entire universe need not arm itself to crush him. A vapor, a drop of water suffices to kill him. But, if the universe were to crush him, man would still be more noble than that which killed him, because he knows that he dies and the advantage which the universe has over him; the universe knows nothing of this.”

–Blaise Pascal

******************************************

The biblical cosmogonist described the creation of the universe thusly: “God made two great lights—the greater light to govern the day and the lesser light to govern the night. He also made the stars.” From the worldview of the biblical authors, the belief that God “also made the stars” – as if such work was an easy lift compared to the creation of the sun and moon – makes sense. After all, to them the entire cosmos consisted of three realms: the heavens above where God dwelt, the earth upon which humans lived, and the ground below where the abode of the dead was.

No one (as far as I/we know) had yet gathered that our entire world is just one tiny rock floating around a relatively small star on the outskirts of a galaxy with 100-400 billion other stars in it, which itself is just one of 100-200 billion other galaxies in the vast expanse of the cosmos. Providing some perspective of where we stand in relation to the universe, the Hubble Space Telescope took an array of pictures in late 2003 and early 2004 that were combined to form the furthest image ever captured of the universe at the time. Pointing to a narrow sliver of the sky within the constellation Fornax (encompassing about 1/13,000,000 of the total area of the sky), the telescope captured approximately 10,000 galaxies in the photo, some of which likely date back to near the beginning of the universe.

Hubble’s Ultra-Deep Field Photograph

Such immensity is unsettling: in the entire universe, the human species is adrift on a miniscule speck within a crushingly vast expanse, filled with objects whose size and qualities defy imagination. A picture taken by the Voyager I space probe situates the earth in this context. At Carl Sagan’s urging, NASA’s imaging team positioned the cameras on the probe as it was leaving the solar system in 1990 to capture an image of earth. What Voyager I caught was a speck of light comprising less than a pixel in the photograph.

Pale Blue Dot

That small, little dot in the maroon band of light on the right side of the picture – “That’s here. That’s home.” Viewed in this light, “He made the stars also” is unintentional rhetorical understatement if there ever was such a thing.

Long before these modern cosmological breakthroughs, however, Blaise Pascal was already busy reflecting on the existential implications of the apparent irrelevancy of our own existence in the grand scheme of the cosmos. In his Pensees, he wrote:

When I survey the whole universe in its dumbness and man left to himself with no light, as though lost in this corner of the universe, without knowing who put him there . . . I am moved to terror, like a man transported in his sleep to some terrifying desert island, who wakes up quite lost and with no means of escape.

This terror starkly contrasts with the Psalmist’s view, who found in the heavens comforting proofs of the divine: “The heavens are telling the glory of God; and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.”

Nobel laureate Steven Weinberg goes one step further than Pascal. As he contends in Dreams of a Final Theory, “The stars tell us nothing more or less about the glory of God than do the stones on the ground around us.” What to the Psalmist seemed like incontrovertible proof for God has become to us reason to think the opposite. As science continues to demystify the universe around us, the explanatory role that the Deity once filled increasingly diminishes – the Ever-Shrinking “God of the Gaps.” “God made it that way” has given way – slowly at first, but with increasing rapidity over time – to “those are the laws of nature.” And in light of this demystification that, to many, diminishes the intellectual urge to speculate about a First Cause, Weinberg senses that there is little room left for belief in God. Instead, Weinberg has found a “chilling impersonality in the laws of nature,” a result of the “demystification of the heavens” that started with Copernicus and continues on to this day.

John Polkinghorne, renowned physicist and theologian, was not unaware of this problem, observing in Traffic in Truth that, in the modern era, “One god who is well and truly dead is the god of gaps.” For Polkinghorne, however, this is liberating: “No one should shed a tear about this since the god of the gaps was only a pseudo-deity anyway. He faded away with every advance of knowledge, like a kind of divine Cheshire cat.” If God truly exists, he will not be found residing in the few ultimate gaps that might remain in our knowledge of the cosmos: such a god could exist, but it would hardly suffice to be the God described in the Bible (or other monotheistic religious texts, for that matter). Instead, Polkinghorne, drawing on Pascal, suggests that it is not in empirical signs but rather in our experience as thinking beings that we find reason for belief in God: “Human beings are just reeds . . . but we are thinking reeds and that makes us greater than all the stars, for we know them and ourselves and they know nothing.” It is not in specific convictions about where and how God fits into the universe, but rather in basic intuitions about ourselves that point to the presence of the Divine.

Maybe the fact that we are self-aware is an accident of evolution, being merely the product of naturally-occurring chemical and biological phenomena. After all, if the Drake equation has any proximate relation to reality, intelligent life comparable to human civilization was and is bound to develop in the universe many times over. Perhaps Pascal is right, then, when he is at his most pessimistic: “We run heedlessly into the abyss after putting something in front of us to stop us seeing it,” with that “something” being belief in God or religion in whatever shape or form it takes. Such is the conclusion of Weinberg and many others. Given how disheartening nihilism can be, it makes sense that we would avoid that reality by coming up with something to explain our experiences beyond “things just happen that way.”

I am, however, skeptical of such . . . skepticism. Yet I am uncertain of the contrary Proposition as well. I believe that is because neither Anselm nor Dawkins, Pascal nor Weinberg, can ultimately lead us to deduce the correct answer to a matter that cannot be tested in a laboratory and reproduced in experimentation. It’d be nice to be able to look up at the night sky and, like the authors of Genesis and the Psalms, find the universe a simple, ordered realm that provides surefire proof for the existence of God. With all we know, however, I find myself unable to do so.

Yet I do not find this an impenetrable barrier to faith. As I get older, I increasingly find true and relevant the old adage that the more you learn, the less you know. Life is not a journey of progressive certainty but rather a quest into deeper complexity and mystery. If the Deity exists, I do not think he will begrudge me a healthy skepticism, and I will happily concede, when the time comes, that I have spoken “of things I did not understand.” In the meantime, I will take comfort in the ambiguity of the cosmos and the prospect of the Divine – after all, “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.”

Share this: