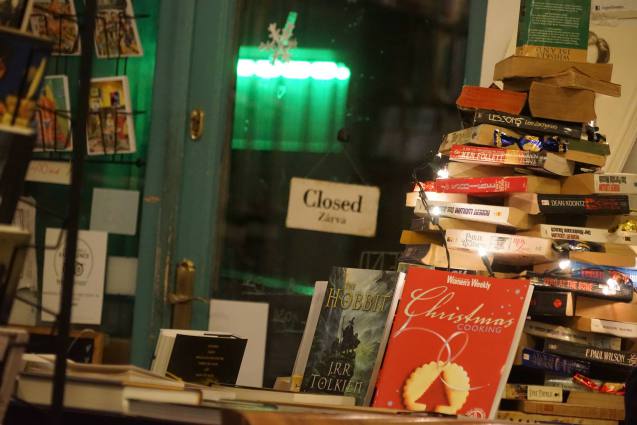

So honored to feature an essay from a very talented writer, and good friend of mine, Sophia Robele. I hate that I had to put any of my words first but I wanted to at least announce that I didn’t write this and give y’all the opportunity to see more of Sophia’s work. She took the photos too!

Sometimes I wonder at the source of my own interests.

You would think this would be an obvious, unnecessary thing to question: the reason you are drawn to the things you are. It is one of those things that just is. It is one of those things that make you who you ‘are’, that shapes this mysterious thing of ‘identity’, a concept that can easily feign concreteness through the existence of a word to so simply define it. But lately, in particular, I’ve wondered at the reason for the types of books I’ve connected with and continue to seek out. The past few weeks, as I’ve made a concerted effort to do more reading for pleasure, I noticed some patterns to the books I was choosing; and I say ‘noticed’ because these didn’t necessarily feel like conscious factors in my decisions as I was making them. In noticing it after the fact, it felt like I was uncovering bits of information about myself from little clues I’d gathered, offered up unintentionally by my subconsciousness.

I know that when it comes to things like interests or desires or motivations for acting, not everything is always grounded in deeper meaning or specific reason, but I can’t help but wonder whether my recent book choices might speak to some truths or longings I am seeking whilst not necessarily fully cognizant of my own quest…

–The Light of the World: A Memoir by Elizabeth Alexander – A poetic and deeply honest memoir on the loss of a spouse

–Beloved by Toni Morrison – A classic piece of literature and necessarily disturbing account of the psychological dimensions of slavery

–Changes: A love story by Ama Ata Aidoo – A narrative of a driven, independent woman in modern-day Nigeria who enters into a polygamous marriage

–Ghana Must Go by Taiye Selasi – A story of a family with roots in Ghana and Nigeria spread across the world, brought back together by the death of the father that abandoned them and forced to reckon with the complexities of love, loss, and pain that overshadows each of their lives

–Nervous Conditions by Tsitsi Dangarembga – now, just starting, a coming of age story about a girl in colonial Rhodesia…or so the book summaries tell me

On the one hand, the common thread between my choice of reading material may seem like an intentional one: all being books authored by African or African-American writers for one. I think the only conscious thing I was searching for, however, even if never fully articulated in this way at first, was something to connect me to home. This I mean in the broadest possible sense of course – having essentially no real connection with any of the authors or characters in terms of physical origins. Rather, my longing was more for home as conceived in terms of sentiments: belonging, a sense of presence, love, wholeness, connection, and just deeply felt emotions in general… and for the way these things have at different moments in my life made themselves known to me in my various physical locations, lodging themselves in my memories along with the recollection of the people or places with which they are associated.

But again, none of the books in particular held much relevance to any of my memories of home even in this abstract sense. With the exception of maybe the one I’ve now picked up taking place in Zimbabwe (although several decades ago) where I recently lived, or the fact of my African roots more broadly, the characters, places, and events of each held no evident connection to my past or self-definition. And yet, after reading them, I found exactly what I was looking for – as if some subconscious intuition knew something I didn’t, could sense the connection to my own life in the very different lives of those I absorbed through these stories even before I picked them up. This also probably had much more to do with the incredible genius and skill of the authors themselves and the power of art more broadly than the mysterious wisdom of my own subconscious.

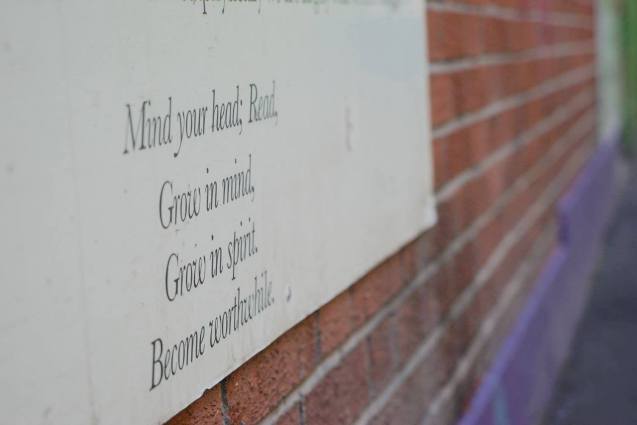

In thinking of this connective power, I was recently struck by the unintentionally profound comment of a friend in response to my questioning of his motivation for doing graffiti art some decades ago. He pointed out the lack of altruism or higher purpose in his motives (perhaps what he thought my question was aiming at), making clear that it was nothing but pure egoism that brought him to put spray paint to wall in those days. Perhaps it is the nature in which I tend to bring up art as this thing of paradigm-shifting and social movements and a force with incomparable and singular value in our world, but I had a feeling that my friend’s answer was a direct response to this assumption that I equated art with loftiness of purpose. And perhaps I have at times sought this intentionality from art…seeking out artists at their gallery openings for instance to ask whether they meant for the meaning that came through in their work, whether they created such pieces with this meaning in mind. But in my friend’s response I was reminded of this quality of art to transcend the individual precisely for its individualistic, and at times even egotistic, qualities.

It seems no coincidence that some of the most universally moving and inspiring forms of art seem to come from creations which arise primarily out of a focus on the self. They are not outputs driven by some motive to necessarily influence the emotions or opinions of others but rather, simply organic outpourings of individual reflection and a generosity of self. Without seeking it, these works arrive at something moving and powerful for the reader or viewer precisely because the artist did not contort his or her authentic ideas and forms of expression to fit this role of influence and larger purpose. At the same time, maybe some distinction is required between the individual and the ego, as the latter’s association with an inflated sense of self-importance would probably diminish the clarity and authenticity of such creations – thus perhaps it is more accurately the individualism rather than the egotism that is the powerful motivating source…

Still, in the context of the written word in particular, many writers have in fact explicitly spoken of the ego as functioning at the center of most writing. On the extreme end, the writer Joan Didion’s description of writing as “the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind” very directly acknowledges the self-centered and influence-seeking dimensions of writing. I am not sure I wholly agree with the implications of such a description, however, I found Didion’s further explanation of her own motivations for writing to better reflect the kind of valuable individualism at the heart of moving pieces of work: “Had I been blessed with even limited access to my own mind there would have been no reason to write. I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means.” Ultimately, it is an impulse grounded in a desire to make sense of the things within one’s own mind and of one’s own experiences and reactions to the world. In doing so, I think the product inevitably becomes something universal, because it speaks to an impulse which we all share.

In the case of a memoir like the one I read by Elizabeth Alexander, the product may be seen to constitute the epitome of an outpouring of self – entirely fabricated out of the individual experience and the writer’s desire to share the deeply personal contours of her own pain and joy and humanity. Alexander’s description of the process of writing the memoir seems to echo the idea of interior searching giving rise to something potent, explaining: “I was keenly aware that the writing came from the same place within me where poetry resides, somewhere lyrical and partially unknown such that the process of writing is a process of revelation. I didn’t choose this form, it chose me – for exploring the zone of intense love and grieving, as well as for the indelible force of life and its power and beauty…” I found something unexpectedly relatable not even in the events or experiences of the author but in the kind of chaotic and random collecting and searching and sense-making of her most personal memories. In the case of this memoir, the memories are those of grief and love and all the deepest complexities of human emotion – perhaps better described as poetic abstractions of feelings more than precise retellings of past events. And coming from these deeply emotional origins, the writing felt laden with a sort of honesty freed from the constraints of intentionality or forced motivations in relation to the reader. Every word, every passage, every paragraph felt like something that needed to be said by its owner, allowing profound glimpses into another’s past as viewed through her own love- and grief-tinted lens.

Just as Alexander’s memoir felt relatable in its deeply individual quality, the perceptions and emotions expressed by the characters in the fiction piece Ghana Must Go by Taiye Selasi held a similar quality of universality in the details. Although I have very little in common with the characters, and particularly the major traumatic life events shaping their identities like grappling with the abandonment of a father, I kept finding myself relating to the tiniest of details throughout the narrative. Most notably, I kept having this sense of something being revealed to me about my own feelings – as though someone had put to words things I had always felt but never really gave definition to for lack of a means to formulate it.

Just as Alexander’s memoir felt relatable in its deeply individual quality, the perceptions and emotions expressed by the characters in the fiction piece Ghana Must Go by Taiye Selasi held a similar quality of universality in the details. Although I have very little in common with the characters, and particularly the major traumatic life events shaping their identities like grappling with the abandonment of a father, I kept finding myself relating to the tiniest of details throughout the narrative. Most notably, I kept having this sense of something being revealed to me about my own feelings – as though someone had put to words things I had always felt but never really gave definition to for lack of a means to formulate it.

Many of these details were quite minor, but nonetheless, profound merely in their incisive articulation of feelings or thoughts I’ve also had – bringing with them some mysterious insight into the nature of connection and commonality between the workings of my own mind and that of others. For example, one passage described a character standing outside a row of buildings in a wealthy, predominantly white area of New York, just pausing outside to observe the way the light radiated a homely warmth through each of the little windows: “What bewitched her was all those warm windows…that warm-yellow-glowing-inside-ness of home.” Of course, this comment had a larger purpose within the specific context of the novel and what the character felt in thinking it, but I was simply struck by the accuracy of the words themselves: giving concreteness to a feeling I’ve also felt in observing something as simple as warm-yellow-glowing lights in the homes of others.

Equally so, some of the details held relevance to much larger experiences – in some cases actually allowing me to see my own sentiments in a completely new light through the fact of having access to it on paper. The best example of this was in the description of the scattered family in the book as “weightless”…”a family without gravity, completely unbound. With nothing as heavy as money beneath them, all pulling them down to the same piece of earth, a vertical axis, nor roots spreading out underneath them, with no living grandparent, no history, a horizontal…” Although its relevance to my life took on a different connotation than its application to those in the story – in my case, not associated with any kind of broken home or destructive voids – it nonetheless felt like a mini revelation: shedding light on something I’ve felt of my own family experience and the lives we inhabit in relation to one another. In short, it gave new shape and meaning to my own formulation and re-formulation of home and identity.

Without over-inflating an experience which was simultaneously quite small and simple in nature (and derived value also in this fact), I think the collection of these mini revelatory moments gathered through the pages of these books simply reminded me of the gift that is another person’s impulse and willingness to create and share: to offer up a little piece of themselves either directly or through the lives of those they fashion on paper, releasing it into the world such that another might grasp on and make it their own.

Advertisements Share this: