It’s Never Over Even When It Is

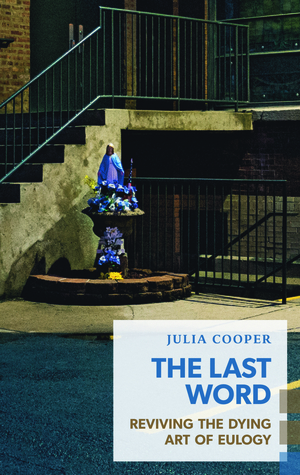

The Last Word: Reviving the Dying Art of Eulogy

By Julia Cooper

A book review by Pam Munter

You scan through Amazon.com or wander through your nearest bookstore and come across a book called The Last Word: Reviving the Dying Art of Eulogy by Julia Cooper. What do you think you’ll find when you start to read? A history of eulogies and how they’ve become disappointingly mundane? The sad decline in the incidence of clever eulogies in our culture? A comic send-up of bad eulogies? How about something about the art of a Friars-like roast of the deceased? Or even a how-to book on how to enliven (sorry) the perfect eulogy? If you expected any of this, you’ll be disappointed.

You scan through Amazon.com or wander through your nearest bookstore and come across a book called The Last Word: Reviving the Dying Art of Eulogy by Julia Cooper. What do you think you’ll find when you start to read? A history of eulogies and how they’ve become disappointingly mundane? The sad decline in the incidence of clever eulogies in our culture? A comic send-up of bad eulogies? How about something about the art of a Friars-like roast of the deceased? Or even a how-to book on how to enliven (sorry) the perfect eulogy? If you expected any of this, you’ll be disappointed.

Instead we’re taken on an amusement park ride through various lands. We begin in DianaLand, where Cooper talks about her first real experience of death, transfixed while watching the Princess’s funeral on TV. That viewing, however, seems to sow the seeds of her cynicism surrounding the whole process. Western culture, she says, just wants those bad feelings over with to facilitate an easy return to a sunnier life view. “Positive thinking requires deliberate self-deception, including a constant effort to repress or block out unpleasant possibilities and ‘negative’ thoughts.”

Next we veer off into CelebrityLand, a frequent stop it turns out. We get a critique of David Bowie’s funeral, followed by that of Prince and of the contemporary phenomenon of the “instant eulogy” via Twitter. Again, the edgy observation: “…the user who gets to the keyboard first and breaks the news is transformed by her untimely tweet into Top Griever…a personal news source to others.” There is a good deal of information throughout the book about the funerals of celebrities, in fact, which underscores the inherent lack of focus and a disappointing reliance on secondary sources. At times, however, it seems more like a grief memoir.

The personal lamentation arises from the death of her mother. “…I knew I didn’t want to get over it. Amid this disorientation…(it) felt like the only thing I truly knew about myself. Losing my mom, I became broken.” Now we understand. This well-educated, articulate writer is working through her own anguish by traveling through the disparate lands of death. This is a valid perspective and seems to be a genuine departure from the rest of the book. More about this personal and relatable journey would have been welcome.

However, we move on. Next stop: GreekLand where we get a brief tour of Greek orations, before entering a time tunnel and briefly lingering in FreudLand. She resents the pioneering psychoanalyst for warning us that too much grieving can slip into melancholia, eliciting another diversionary finger-wagging lecture. “As it turns out, one of science’s favourite (sic.) tools is pathologization (sic.)—the categorization of anything other than ‘normal’ as some form of sickness, ailment or aberration.” She rhetorically muses, “What would it mean to allow myself to be sad for as long as I needed?” Again, we can see that her filter is her painful personal agenda.

Succeeding chapters embrace funerals and eulogies in fiction, including many popular films as well as the work of respected NonfictionLand writers like Joan Didion, David Foster Wallace and Norman Mailer. Still, she persistently comes back to her own experience of grief, cloaked in what seems like significant amounts of pique. While she admits to finding Didion’s memoirs on death comforting, she can’t resist a snipe or two. “I found myself chafing against the nonchalance with which her immense wealth comes out in her prose. She coats her suffering in a high-gloss veneer and occasionally seems stunned that her money did not protect her from pain.”

Without irony, she quotes from Norman Mailer’s essay about his own eulogy, written 28 years before his death. In one of the more compelling parts of the book, she acknowledges the need we all have to manage the perceptions people have of us, postulating a common fantasy of writing our own eulogies as a way to manage how our death is processed by others. This is the most readable chapter in the book and could have been easily expanded.

But by this time, the book has become a free-associative, extended essay, darting toward various topics but not lingering or digging very deeply. Here and there, she includes observations about the social niceties of grief rituals but this is supposed to be about eulogies. Her anger is rekindled when she discusses society’s discomfort with a woman’s anger over a death (clearly speaking once more of her own experience), then reverts to movies to tell us plots in which the survivor becomes angry over a fictional death.

Back in FilmLand, we read about the eulogy scene in “Proof.” She suggests a rewrite. Then she describes the circumstances in which Sally Field’s character loses her screen daughter in “Steel Magnolias,” a eulogy played for laughs. In an abrupt transition back to CelebrityLand, she cites Cher, who set aside her written notes when giving ex-husband Sonny Bono’s eulogy. Cooper suggests Cher’s preference for ad libbing was due to her inconsolable grief. “Even Cher, born for the spotlight, falters in the moment of eulogy. She wobbles between talking to Sonny and talking to his mourners, and drifts in and out of memory.” Cher, who has made no secret of her severe dyslexia, was more likely struggling with the words on the page.

But now, wait for it, we’ve briefly returned to FilmLand, in this case “The Big Lebowski.” After setting up the plot points, she writes that this film “takes the amateur art of the eulogy to a purposely ridiculous—and cathartic—extreme.” Her closing example is NonfictionLand’s Cheryl Strayed, who has written extensively of her often dysfunctional response to the death of her mother. Again, it’s personal for Cooper. “Reading ‘Wild,’ I found lines…which made me feel as though I was (sic.) reading about my own mom.”

When the reader puts down the book at the end (if you make it that far), you likely feel as though you’ve been on a wild ride through way too many lands. The strongest sections pertain to the relevant topic of eulogies but the detours are legion. There’s no end summary, either, to reorient us and remind us of the reason for the book. Her closing maxim is that the dead are always with us. “Mourning is just a reminder that humans intuitively know loss more keenly than we know anything else.” If this were acknowledged to be a memoir instead of proferred as narrative nonfiction, we might be more agreeable.

Pam Munter has authored several books including When Teens Were Keen: Freddie Stewart and The Teen Agers of Monogram. She’s a retired clinical psychologist and former performer. Her essays and short stories have appeared in The Rumpus, The Manifest-Station, The Coachella Review, Lady Literary Review, NoiseMedium, The Creative Truth, Adelaide, Litro, Angels Flight—Literary West, TreeHouse Arts, Persephone’s Daughters, Better After 50, Canyon Voices, Open Thought Vortex, Fourth and Sycamore, Nixes Mate, Scarlet Leaf Review, Cold Creek Review, Communicators League, I Come From The World, Switchback, The Legendary and others.

Share this: