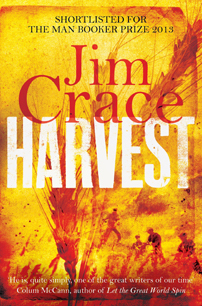

A lyrical beauty of a novel, Jim Crace’s meditation on a quintessentially medieval rural England is elegiac yet powerful and politically resonant in today’s climate.

A lyrical beauty of a novel, Jim Crace’s meditation on a quintessentially medieval rural England is elegiac yet powerful and politically resonant in today’s climate.

Social change is thrust upon a small isolated hamlet, two days ride from its nearest village, a place so insignificant that no church dominates its laneways. The arrival of a trio of outsiders is a catalyst to the complete breakdown within seven days of a way-of-life little changed in generations. In erecting four rough and ready walls as a shelter and lighting a fire on common ground, custom and law gives the strangers the right to stay.

Not that are particularly welcome – their arrival coincides with another fire – that of the dovecote and stables of Master Kent, the young, kindly lord of the manor.

Our narrator, Walter Thirsk, deduces who is to blame for that particular inferno. But as an outsider himself, resident only for 10 or so years, he keeps his views to himself. It’s not done apportioning blame on neighbours within such a close-knit community. The new arrivals are duly accused for the fire with the two men clapped in the stocks, the young woman shorn of hair.

Just seven days later, having celebrated the harvesting of the barley, Kent finds himself replaced as the local lord by a superior blood claim to his title by the cruel and ambitious Master Jordan; plans to replace the cropping of the land with the more economical farming of sheep are drawn up; one of the men clapped in the stocks is dead; accusations of witchcraft and murder see Jordan oversee trials by torture: superstitions and suspicion undermine community and family ties and, fearful of repercussions from Jordan and his henchmen, the population has fled, the hamlet abandoned. As the novel draws to its close, only Walter remains. Yet, in spite of having gained the trust of the new lord, he himself has no intention of staying.

Harvest is beautifully written. In spite of the level of events unfolding, this is no breathless potboiler. Crace is meticulous in his wording and phrasing – in its intimacy, his love of words and language is deeply apparent. He succeeds in transporting his reader to the hedgerows of the country lanes, the final evening celebrations of the harvest, the inhumanity of the stocks. It’s a paean to its way-of-life and the time when the sheaf is giving way to sheep, where subsistence agriculture was replaced by profitable wool production: the peasant farmers and communities were dispossessed and displaced. A contemporary resonance.

Jim Crace’s reportedly last novel was awarded the 2015 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award and was shortlisted for the 2013 Booker Prize, but lost out to New Zealander Eleanor Catton and The Luminaries.

Advertisements Share this: