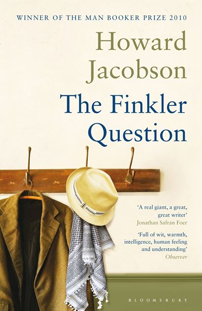

Having read English at Cambridge under F. R. Leavis and taught the subject at Selwyn College, Cambridge, you just know anything written by Howard Jacobson will not fall under ‘light read.’ But what you may not be prepared for is the wit, irony and warmth alongside the satire and intelligence. Even on a second reading, The Finkler Question made me laugh out loud.

Having read English at Cambridge under F. R. Leavis and taught the subject at Selwyn College, Cambridge, you just know anything written by Howard Jacobson will not fall under ‘light read.’ But what you may not be prepared for is the wit, irony and warmth alongside the satire and intelligence. Even on a second reading, The Finkler Question made me laugh out loud.

Jacobson is tackling one mighty difficult and potentially contentious issue in The Finkler Question – that of Jewish identity alongside male friendship.

It is through the friendship of three men – former schoolmates Julian Treslove and Sam Finkler and their teacher, Libor Sevcik – that Jacobson explores his subject, an exploration that is at once brilliantly funny yet with a deep melancholic sense of loss and longing.

Through the three men, opinions and opposing philosophies of what exactly is Jewish identity are voiced, discussed and debated – from the strident, anti-Zionist, Israeli-hating Finkler through to the ‘convert’ that is Treslove, more orthodox than any of his friends as he reads 12th century Maimonides on the reasoning for circumcision or demands answers to his questions of, how he sees it, the innate ‘Jewish’ cleverness of the use language. A 90 year-old Czech, Libor sits somewhere between the two men.

A former BBC radio producer (a minor position – an early morning arts programme on Radio 3), Treslove is a melancholic lost soul – a father of two (adult) boys to separate women, both of whom chose not tell him of their respective pregnancies. His great love is the great operatic tragedies. It is he who labels Jews at Finklers, having met his first Jew at school in the guise of Sam/Samuel/Shmuel/Shmueli (several identities in one…). This new word “…took away the stigma, sucked out the toxins.” A late night mugging a few yards from the BBC in Portland Place following an evening with Sam and Libor leads to Julian questioning his sense of who and what he is.

As a result, The Finkler Question becomes, in part, Julian as a Gentile and his relationship with Judaism and ‘Jewishness’. But in ostensibly looking at Libor, Sam and other characters as Jews and how Julian ‘measures up’, The Finkler (Jewish) Question is as much about the sense of belonging and the associated obligations/expectations of that belonging.

As an anti-Zionist, is Sam a lesser Jew? Hephzibah only introduces a kosher kitchen at the behest of Julian yet she is the director of the planned Anglo-Jewish Cultural Centre. Tyler, Sam’s wife, was a convert. Yet, in spite of her upholding the religious customs and beliefs more than Sam, as a reformist, she was not totally accepted. And deep down, Julian himself despairs of the religion that he does not fully grasp or can ever, ultimately, be part of.

The Finkler Question is something of a meandering narrative, jumping in time and place. It verges on plotless per se other than as a stream of (Jewish) consciousness. Julian finds some of the answers to his questions: some of the questions he doesn’t understand himself. Both Sam and Libor deal with their grief at the loss of their wives in their own ways.

Anti-Semitism does rear its ugly head in obvious ways but also in surprising ways – The Finkler Question continues to challenge and question assumptions. People – Jews and non-Jews alike – come ago, vehicles for Jacobson to propound yet more opinions (occasionally over-contrived – Julian’s youngest son a Holocaust denier). And Treslove’s neurotic obsession occasionally palls (Maimonides?).

But the 2010 Booker Prize winner is a seamless roll of pathos and humour, of philosophy and politics, relentless in its search for a truth. Not that Jacobson is going to answer The Finkler Question – mainly because there is not one answer. Put two Jews in a room and you’ll get three very different opinions. Welcome to The Finkler Question.

Advertisements Share this: