Part Of: Demystifying Ethics sequence

Content Summary: 900 words, 9 min read

Trolleyology

An ethical theory is an attempt to explain what goodness is: to ground ethics in some feature of the world. We have discussed five such theories, including:

- Consequentialism, which claims that goodness stems from the consequences of an action

- Deontology, which claims that goodness stems from absolute obligations (discoverable in light of the categorical imperative)

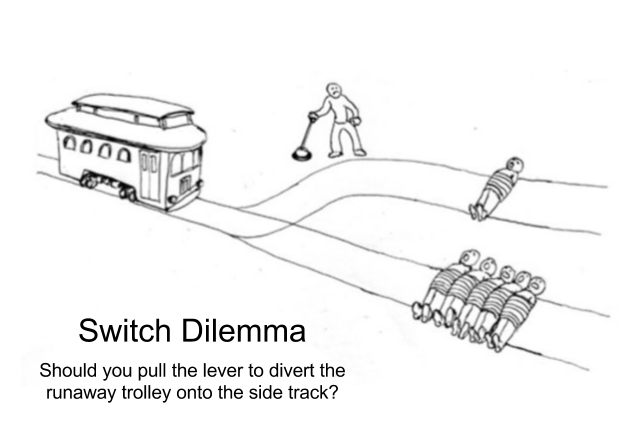

For most behaviors (e.g., theft), both theories agree (in this case, label the act as Evil). But there do exist key scenarios which prompt these theories to disagree. Consider the switch dilemma:

Consider a trolley barreling down a track that will kill five people unless diverted. However, on the other track a single person has been similarly demobilized. Should you pull to lever to divert the trolley?

Our ethical theories produce the following advice:

- Consequentialism says: pull the lever! One death is awful, but better than five.

- Deontology says: don’t pull the lever! Any action that takes innocent life is wrong. The five deaths are awful, but not your fault.

Would you pull the lever? Good people disagree. However, if you are like most people, you will probably say “yes”.

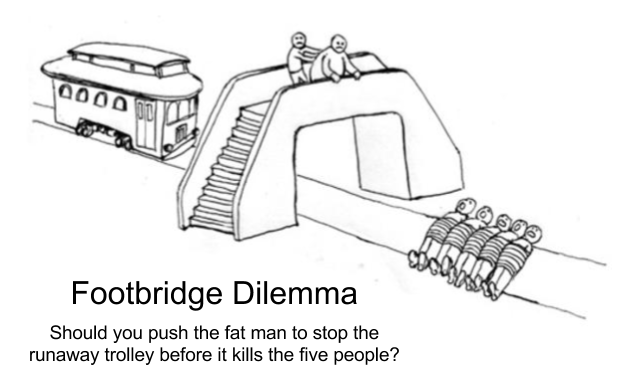

Things get interesting if we modify the problem as follows. Consider the footbridge dilemma:

Consider a trolley barreling down a track that will kill five people unless diverted. You are standing on a bridge with a fat man. If you push the fat man onto the track, the trolley will derail, sparing the five people.

Notice that the consequences for the action remain the same. Thus, consequentialism says “push the fat man!”, and deontology says “don’t push!”

What about you? Would you push the fat man? Good people disagree; however, most people confess they would not push the fat man off the bridge.

Our contrasting intuitions are quite puzzling. After all, they only thing that’s different between the two cases is how close the violence is: far away (switch) vs up close (shoving).

Towards a Dual-Process Theory

Recall that there are two kinds of ethical theories.

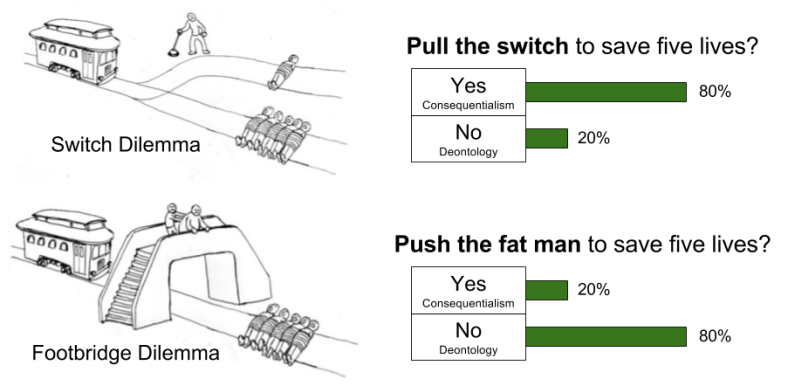

Consequentialism and deontology are prescriptive theories. However, we can also conceive of consequentialism and deontology as descriptive theories. Let’s call these descriptive variants folk consequentialism and folk deontology, respectively.

Sometimes, people’s judgments is better explained by folk consequentialism; other times, folk deontology enjoys more predictive success. We might entertain two hypotheses to explain this divergence:

As we will see, the evidence suggests that the second hypothesis, the dual-process theory of moral judgment, is correct.

Dissociation-Based Evidence

Consider the crying baby dilemma:

It’s wartime. You and your fellow villagers are hiding from nearby enemy soldiers in a basement. Your baby starts to cry, and you cover your baby’s mouth to block the sound. If you remove your hand, your baby will cry loudly, and the soldiers will hear. They will find you… and they will kill all of your. If you do not remove your hand, your baby will smother to death. Is it morally acceptable to smother your baby to death in order to save yourself and the other villagers?

Here, people take a long time to answer, and show no consensus in their answers. If the dual-process theory of moral judgment is correct, then we expect the following:

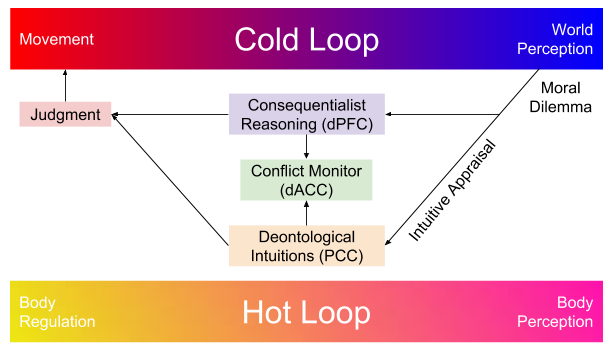

Both predictions turn out to be true. Here then is the circuit diagram of our dual-process, organized in the two cybernetic loops framework:

Four other streams of evidence corroborate our dual-process theory:

- Deontological judgments are produced more quickly than consequentialist ones.

- Cognitive distractions slow down consequentialist but not deontological judgments.

- Patients with dementia or lesions that cause “emotional blunting” are disproportionately likely to approve of consequentialist action.

- People who are either high in “need for cognition” and low in “faith in intuition”, or have unusually high working memory capacity, tend to produce more consequentialist judgments.

Relation To Other Disciplines

We have previously distinguished two kinds of moral machinery:

- Propriety frames are a memory format that retains social intuitions.

- Social intuition generators which contribute to the contents of social judgments.

These machines map to the dual-process theory of judgment. Propriety frames are housed in cerebral cortex, which perform folk consequentialist analysis. Social intuition generators are located within the limbic system, and contribute folk deontology intuitions.

Recall that Kantian deontology attempted to ground moral facts in pure reason (the categorical imperative). While surely valuable as a philosophical exercise, in practice folk deontological judgments have little to do with reason. They are instead driven by autonomic emotional responses. It is folk consequential judgments which depend more on reason (cortical reasoning).

This is not to say that people who prefer consequential reasoning are strictly superior moral judges. But I will address the question which reasoning system should I trust more? on another day.

Takeaways

- For the switch dilemma, most people reason consequentially (“save the most lives”)

- For the footbridge dilemma, most people reason deontologically (“murder is always wrong”)

- These contrasting styles emerge because the brain has two systems of judgment.

- Folk consequentist reasoning is performed in cerebral cortex.

- Folk deontology intuitions are generated from within the limbic system.

Until next time.

Advertisements Share this: