Between mines and mills and factories, there are more steam engines per person in Wigan than in London, Pittsburgh, Essen or anywhere else. It happens to fit nicely that the palm oil we import from Africa lubricates those engines. The world runs on coal, and Wigan leads it. As long as we have coal we will continue to do so.’

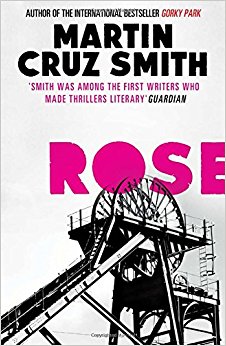

As I mentioned in my last post, I’ve just finished reading Rose, a novel by the American thriller writer Martin Cruz Smith set in Wigan in the 1870’s. It tells the story of one Jonathan Blair, an American mining engineer who, on returning from Africa in disgrace is employed, reluctantly, to visit the town to investigate the disappearance of a curate who was engaged to his patron’s daughter.

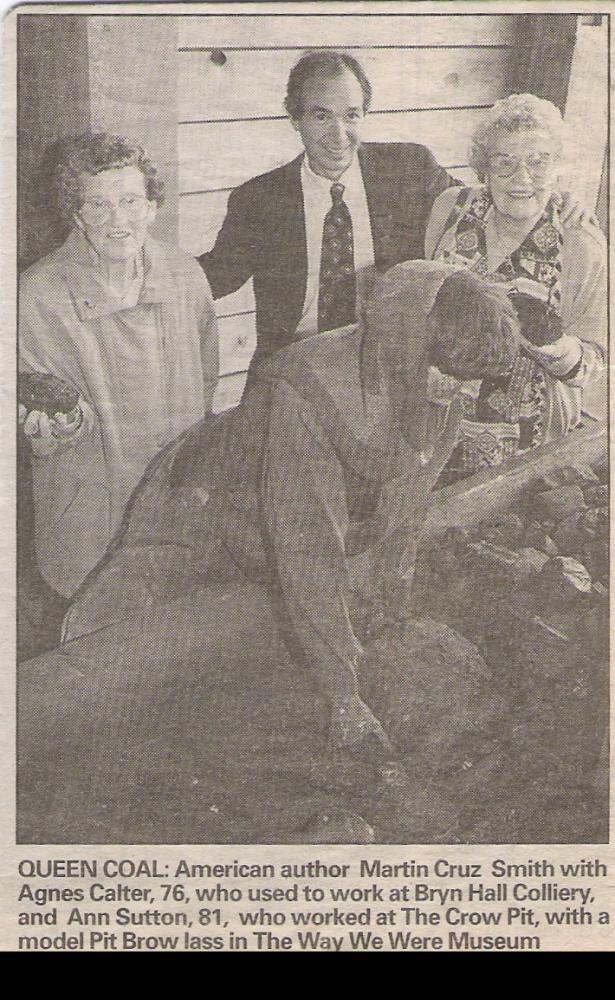

The author had certainly done his research and weaves details about working class life in Wigan 19th-century into his story. He visited the town and met with local historian and some former pit brow women. Here’s a cutting from the local paper

In an interview in 1996 he reveals that he was a fan of George Orwell and had read The Road to Wigan Pier. and I’m sure that it’s no coincidence that his hero is called Blair, the real name of Orwell was Eric Blair.

Wigan, a working class town built on coal and cotton, wasn’t a pretty place during Victorian times and I’m sure his description of Wallgate is accurate

The thought occurred to Blair that if Hell had a flourishing main street it would look like this.

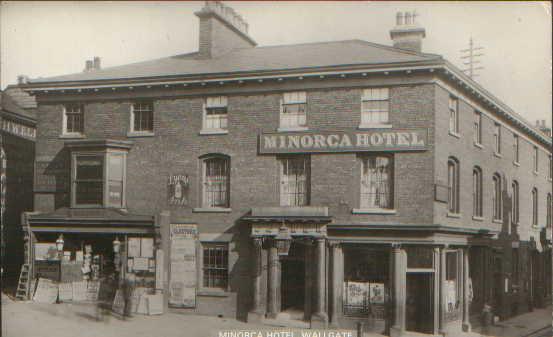

I found it fascinating to read the names of places I knew in the book. His hero stayed in the Minorca Hotel on the corner of Wallgate and King Street. It’s still there, but has gone through several name changes over the years – it’s now called the Berkeley and at one time was known as Blair’s. Here’s how it looked in about 1900

The Minorca Hotel on Wallgate (from Wigan World website)

Various pubs are mentioned, there were a large number in Wigan, including the one nearest to where I live, the Balcares (now renamed the Crawford Arms) on Scholes – the name of both a thoroughfare and a district of the town just west of the town centre. In fact much of the novel is set in Scholes, which at the time was populated by miners and other workers packed in back to backs and houses built off dark, narrow courtyards.

Scholes, Wigan, 1890’s (from Wigan World website)

The slums were cleared in the 1960’s and I lived there for a few years in a Council flat. And now I’m only a few minutes walk away from the district. So it was rather odd to be reading about the same streets and Scholes bridge, which I still cross regularly, in a novel by an International renowned author.

His descriptions of working in the mines are excellent, and really bring the experience of going down a mine to life

The cage started slowly, down through the round, brick-lined upper mouth of the shaft, past round garlands of Yorkshire iron, good as steel, into a cross-hatched well of stone and timber and then simply down. Down into an unlit abyss. Down at twenty, thirty, forty miles per hour. Down faster than any men anywhere else on earth could travel. So fast that breath flew from the lungs and pressed against the ears. So fast that nothing could be seen at the open end of the cage except a blur that could whip away an inattentive hand or leg. Down seemingly for ever.

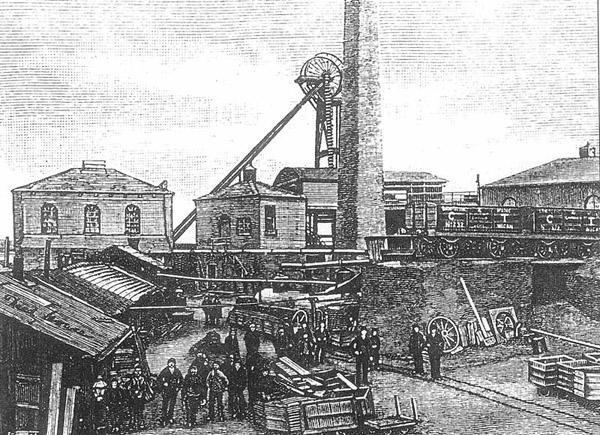

Mains Colliery, Bamfurlong 14th Dec 1892 (from Wigan World website)

Blair crawled out into a narrow tunnel, the length of which was populated by shadowy figures wearing only trousers and clogs, some only clogs, covered by a film of dust and glitter, swinging short, double-pointed picks. The men had the pinched waists of whippets and the banded, muscular shoulders of horses, but shining in the upcast light of their lamps what they most resembled was machinery, automatons tirelessly hacking at the pillars of coal that supported the black roof above them. Coal split with a sound nearly like chimes. Where the coal seam dipped, men worked on knees wrapped in rags. Other men loaded tubs or pushed them, leaning into them with their backs. A fog of condensation and coal dust rose from them.

Miner hewing coal (from Wigan World website)

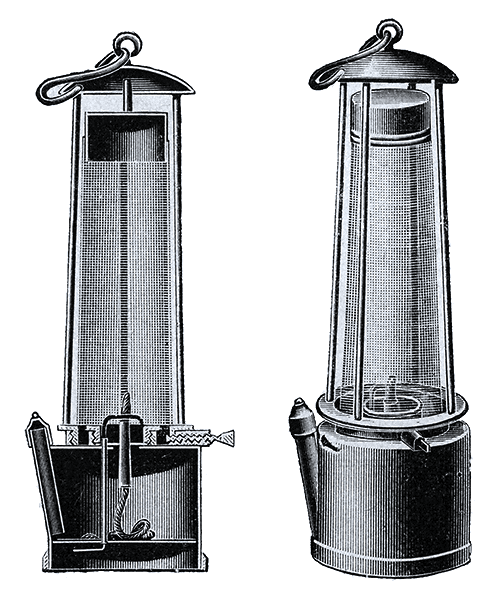

Given my line of work, I was particularly interested to read his descriptions of the dangers posed by firedamp and the way that miners could “read” the danger using their Davy Lamps

From the German Dampf. Meaning vapour. Explosive gas.’ ‘Oh,’ said Leveret. ‘Methane. It likes to hide in cracks and along the roof. The point of a safety lamp is that the gauze dissipates enough of the heat so that you won’t set the gas off. Still, the best way to find it is with a flame.’ Battie lifted the lamp by a rough column of rock and studied the light wavering behind the screen of the gauze. ‘See how it’s a little longer, a little bluer? That’s methane that’s burning.’

And there were other “damps” too

When firedamp explodes it turns to afterdamp. Carbon monoxide. The strongest man in the world could be running through here at top speed, but two breaths of that and he’ll drop to the floor. Unless you drag him out, he’ll die. In fact, I’ve seen rescue attempts where one, two, three men will drop trying to pull one man out.

The Davy Lamp (By Scan made by Kogo [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

In designing his lamp, Humphry Davy was largely motivated by a desire to save lives (although the search for glory was a factor too, it has to be said) and he refused to take out a patent, even though strongly encouraged to do so. He wanted his lamp to be freely available. Sadly, although the lamp was intended to save lives it has been said that it actually caused the death of more men because the mine owners used the lamp as an excuse to send their workers into more dangerous workings.

The novel was well written, and not just the details about Wigan and life as a miner. It was a gripping story, if a little far fetched. The ending certainly was. But a good read nevertheless.

Advertisements Like this:Like Loading... Related