Image: Pixabay

A Writer’s NotebookIn the last few years I have become bored with journaling. Oh, I still journal a bit. But I sure don’t fill the reams of paper I used to. A downside of this is that I no longer have the bulk of material to sift through for possible writing ideas that I once did. Add to that the importance common wisdom places on writers keeping notebooks and is it any wonder I’m starting to feel left behind and guilty because I’m neglecting something that’s important for a writer?

Perhaps that’s why a while ago the blog Sharing Our Notebooks caught my attention. Maintained by children’s poet, author, and teacher Amy Ludwig VanDerwater, the blog talks only about notebooks and how people—mostly writers and other creatives—use them. Through it I stumbled on an entire book about writers’ notebooks. I am learning so much as I get educated, not about journaling but about keeping a writer’s notebook. Let me share some of these things with you.

Image: Pixabay

What is a writer’s notebook?

“Let’s start by talking about what it is not,” says Ralph Fletcher in his book A Writer’s Notebook. “A writer’s notebook is not a diary”1

Fletcher goes on to give us some ideas of what a writer’s notebook is. He tells us that though writers experience the gamut of thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations like everyone else, they differ from others in that they take notice of their reactions to those things. And the place to collect those reactions is the writer’s notebook. He concludes: “A writer’s notebook gives you a place to live like a writer … wherever you are, at any time of day.”2

Alan Wright, an Australian author and educational consultant would agree: “People who write get to live life twice—in the moment and in retrospect. That’s what sets writers apart. I rarely go anywhere or do anything without the shadow of my writing self being part of the adventure. Every experience provides opportunities to harvest writing ideas.”3 And the things stored in a writer’s notebook only increase in value, according to teacher and naturalist Bill Michalek: “…the diary-type entries become more and more valuable the older they get … let months or years go by, and those entries are time machines.”4

Image: Pixabay

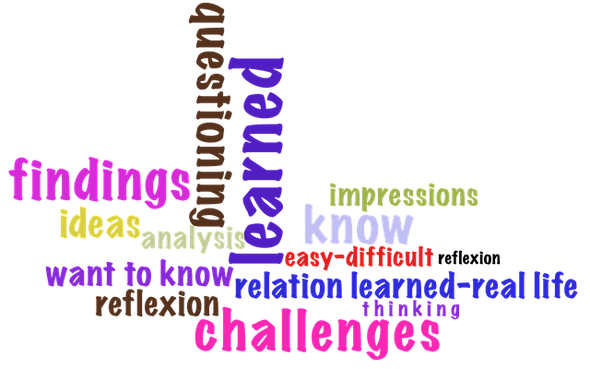

What do we put in a writer’s notebook?The list of possibilities is long and includes:

- Our reactions to life, as discussed above.

- Things that move, haunt, or inspire us. Fletcher says, “People are different. What dazzles one person might bore the next. The question is: what moves you? As a writer, you need to be able to answer that question and take note of it.” 5 Small, telling details of scenes, experiences, and interactions. The advice from more than one notebook-keeper is to train ourselves to notice details and use all our senses to capture our impressions in precise words (not the room “smells nice” but “smells like vanilla”). We need to look for and note the telling detail of body language and facial expression. Fletcher again: “The world is jam-packed with millions of details to notice; in your notebook you’ll only have room for a tiny fraction. Try to select the ones that capture what’s really important.”6

- Ideas. The advice is unanimous on this:

Alan Wright: “I never know when an idea might arrive, so I must be ready to receive it, and my notebook is my catcher.”7

Ralph Fletcher: “It gives you a place to write down an idea before it wriggles out of your overloaded memory.”8

Peter Salomon (children’s author): “I have a dreadful fear of coming up with a great idea and then forgetting it, so notebooks are a lifesaver.”9

- Facts and trivia. One notebook keeper tells how his habit of collecting spider facts led to writing an entire book about spiders.

- Significant objects. Alan Wright collected a group of objects that was meaningful to him, took a photo, and put it in his notebook as a writing prompt. Some people make sure their notebooks come with pockets so they can collect actual artifacts (ticket stubs, programs, photos, and other memorabilia).

- Great writing. Though Fletcher felt guilty the first time he put someone else’s writing in his notebook, he later changed his mind. He says, “I’ve learned that if I’m going to write well, I need to surround my words with the beautiful writing of others.”10

- Idea-sparkers like photos, comic strips, and news articles.

- Overheard dialogue and arguments between strangers, friends, and family.

- Lists. All kinds of lists like the books we’ve read, favourite words, rhyming words, cities visited, movies seen, favourite characters…whatever!

- Ideas for future projects.

- Doodles and sketches.

- Memories.

- Sayings about writing and writers that inspire us and help us persevere.

I could go on, but I’m sure you get the idea.

Image: Pixabay

What makes a good notebook?

I purposely put the question of what sort of book to choose after listing the kinds of things that might go into a notebook, because the choice of book will depend on what we’ll collect in it and how we will use it. Some writers have several notebooks, each for a different purpose. Notebooks vary in size from small enough to fit in a pocket, to large scrapbooks with sturdy pockets. Some people like stitched notebooks with beautiful covers. Others prefer coil-bound scribblers. Sketchers and doodlers may want paper with no lines. Those who write a lot of longhand may want a stiff cover that doubles as a writing surface. Fletcher reminds us: “Your notebook is uniquely yours.”11 Only we can decide what kind of book we will use and what we will put in it.

How can we get a writer’s mileage out of our notebooks?Read and reread it. Poet Naomi Shihab Nye says: “Rereading notebooks is like reliving your life. I think they’re more important than money in the bank.”12

Fletcher suggests that we reread our writer’s notebooks differently than we read a book. “When I read a book or a poem, I am focusing on being the reader. When I read my own notebook my attention is split: I am half-reader and half-writer all at the same time.”13

Here are some questions Fletcher proposes we ask ourselves as we read our notebooks:

“What seems interesting/intriguing to me? What stuff do I most deeply care about? What ideas keep tugging at me? What seems bold and original? Where does the writing seem fresh and new?”14

Mark the ideas/lines/sections you like, choose one, and on a new page of your notebook, work on that idea, clustering, listing or brainstorming around it as you begin to prepare it for prime time.

We need to realize, however, that most of the writing in our notebooks will never germinate into anything. That’s okay too. Because the very act of noticing and writing things down makes us more observant, alert people—all part of the package we need to be successful writers.

Writer’s notebooks are as old as Leonardo Da Vinci. I’m sure they’re not a novel idea to most of us. But if you’re like me and have been viewing your notebook as a place to dutifully keep track of the details of life, or have become lazy about writing things down at all, maybe you’ll join me in making a new start at keeping a writer’s notebook.

************

Footnotes

1 Ralph Fletcher, A Writer’s Notebook, Harper Collins, 1996, Kindle Location (KL) 52

2 Ibid, KL 59.

3 Alan Wright, “The Essential Question – Why?” sidebar box on Living Life Twice , last accessed September 17, 2012.

4 Bill Michalek, “Bill Michalek – The Page is a Listener,” Sharing Our Notebooks < http://tinyurl.com/8p4nhyn >, last accessed September 17, 2012.

5 Fletcher, Op. Cit, KL 122.

6 Ibid, KL 265.

7 Alan Wright, “Alan Wright: My Notebook Is My Catcher,” Sharing Our Notebooks, < http://tinyurl.com/94bxujs >, last accessed September 17, 2012.

8 Fletcher, Op. Cit., KL 333.

9 Peter Adam Salomon, “Peter Adam Salomon: More Emory Notebooks,” Sharing Our Notebooks, <http://tinyurl.com/9ebr6w2>, last accessed September 17, 2012.

10 Fletcher, Op. Cit., KL 1101

11 Ibid., KL 94

12 Naomi Shihab Nye, quoted in Fletcher, Op. Cit., KL 720.

13 Fletcher, Op. Cit., KL 1262.

14 Ibid.

This article has been previously published in the November 2012 issue of FellowScript.

Share this: