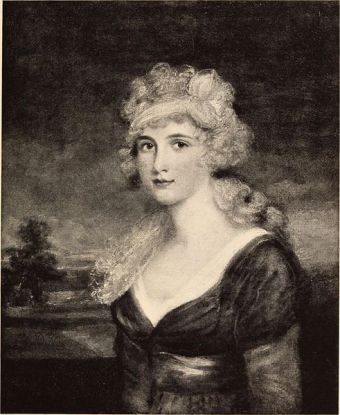

Mrs Jordan, by John Hoppner

Mrs Jordan, by John Hoppner

Dora Jordan was one of the most celebrated actresses of the late eighteenth century. She delighted theatre goers with her repertoire of comedic performances, was a spellbinding tragedian and was renowned for her classic Shakespearean drama, with roles such as Rosalind in As You Like It and Viola in Twelfth Night. She was also one of the women who pushed eighteenth century boundaries for daring to wear trousers on stage in ‘breeches parts’, 150 years before women’s skirts started to rise above the ankle. Actresses were problematic, bringing to the fore questions of sexuality and morality for they entered the public sphere wearing form-fitting clothes and performing bawdy humour on the public stage. Not only was Dora a trailblazer on stage, she also lived a very twenty-first century life.

Dorothy (or Dorothea) Bland was born in London on 22 November 1761. Her father, Franics Bland, was the son of a vicar-general and Prerogative Court judge in Dublin. Her mother, Grace Phillips, who acted on the Irish stage, was the daughter of a Welsh rector. The family lived in Ireland, so it is unclear why they were in London for her birth. Claire Tomalin, Dora’s biographer, suggests that her parents had travelled to the Covent Garden area of London in search of work. Without further clarification, this is a plausible suggestion. She was baptised on 5 December at the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields. However, her parents’ marriage was declared void by her grandfather before she was born. Francis had not reached his majority prior to his marriage and needed his father’s permission, which was denied to them.

Dorothy was one of at least six children and up to her teenage years, lived in what appeared to be, a happy family unit. But then, her father abandoned the family when she was 13, leaving them in Ireland while he went to London to marry an Irish heiress. As Francis’ second family grew, the stipend he had supplied for his first family began to dry up, short of money the older children had to work. Aged 14, Dorothy took a job in a milliners shop in Dublin.

Her father died in 1778, when Dorothy was 17, and it is about this time that she began to appear on stage, at first known as Miss Francis. In 1781, Dorothy joined the company of players at the Crow Street Theatre in Dublin, managed by Richard Daly. There is some dispute over what happened next; but Dora ended up pregnant, seduced or raped, with married Daly as the culprit. Scandal brewing, her place at Crow Street had become untenable, Dorothy and her family fled to England. They met with Tate Wilkinson, her mother’s former colleague, now a manager of a theatre group and pressed for employment. Winning Tate over, he offered her 15 shillings weekly, and a benefit, a chance to earn a large proportion of the profits on a particular night. With a baby on the way, it was advised that she should not be a ‘miss’ anymore. Tate Wilkinson, took the credit for giving her her stage name, comparing her crossing the Irish Sea to Yorkshire with the biblical crossing of the River Jordan. So Mrs Jordan it was. Dorothy preferred to be called Dora, indeed she signed all her correspondence as Dora, so with two other derivatives of Dorothy, she is simultaneously known as Dorothy, Dorothea or Dora Jordon. Or on the playbill, Mrs Jordan.

In November 1782, Dora gave birth to a daughter, Frances, known as Fanny. Back on the stage after her confinement, she travelled the gruelling York circuit with Tate Wilkinson’s company for a further three years. In September 1785, she bade farewell to the strolling players and headed for the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London, to work for Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s company, for she had been offered £4 a week to perform and delight the London elite, and she set about doing that.

She arrived in London with her mother, brother George, sister Hester and two-year-old Fanny, at twenty-three, she was head of the family. She debuted at Drury Lane 18 October 1785 in The Country Girl. One audience member, Mary Tickell, the sister-in-law of the theatre owner, wrote to her sister Elizabeth exalting about Dora’s performance.

“I went last night to see our new Country Girl…she has more genius in her little finger than Miss Brunton in her whole body…though short, she has a certain roundness and embonpoint which is very graceful. Her voice is harmony itself, and I think she has the most distinct delivery of any actor or actress I have heard. Her figure…is uncommonly pretty in boy’s clothes, which she goes into in the third act.”

A week later her celebrated performance had enticed the Prince of Wales into his box, and also his uncle the Duke of Cumberland and former Prime Minister, Lord North, to see the new play at Drury Lane.

The following month, Mary again wrote to Elizabeth, “I think of her by much the best comedian on either stage, or that I ever saw…the papers did not praise her half enough.”

A year later, Dora was rewarded for her efforts with a four-year contract and was soon to act in front of King George III.

As Dora’s star grew, she had a series of liaisons with men who promised much and delivered very little. There was gossip about her male lead on the York circuit, George Inchbald. Wary of her already having another man’s child, he failed to commit to her, only to turn up in London with a proposal once news of her stratospheric rise to fame in London society reached Yorkshire. She refused him politely and not without satisfaction. She had already met her latest beau, Richard Ford, a trainee barrister with political ambitions, she could help support him while he established a practice.

With a private promise between them, they set up home in Gower Street, Bloomsbury. Many people assumed that they had quietly married, for they lived as man and wife. Cohabiting without an officially recognised marriage ceremony subverted strict social mores, and demonstrated fulsomely the immorality and decadence of the theatre that left many suspicious of the actresses’ virtues, for their display on stage was considered unnatural to the female state.

Dora became pregnant very quickly and while on tour in Edinburgh during the close season in August 1787, she gave birth to her second daughter, Dorothea Maria. Still known as Mrs Jordan on stage, she was also called Mrs Ford off it. In the autumn of 1788 she gave birth to her third child, in London, an unnamed boy, who sadly did not survive. During the close season in 1789, she again travelled to Scotland to perform. Her mother had travelled with her, fell ill and died within days. Grieving, Dora made the long return journey home to London and there she gave birth to her fourth child, another girl, named Lucy Hester, after her sisters.

It was in 1790 that it became clear to Dora that Richard would never marry her, even after giving him two daughters. She had skirted scandal since she had left Ireland, but now it would hit her full in the face. After five years with Richard Ford, Dora succumbed to the relentless attentions of the Duke of Clarence and let her dreams of domesticity with Richard fade.

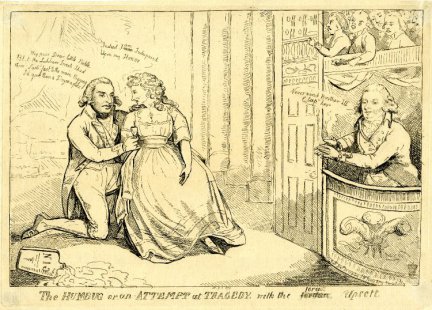

Dora leaves Richard for the Duke of Clarence

Dora leaves Richard for the Duke of Clarence

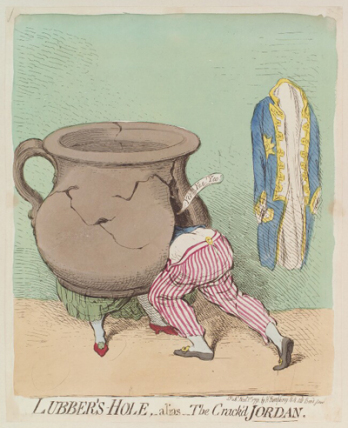

William, Duke of Clarence, was the third son of King George III and the printed press revelled in the ensuing scandal. Dora was viciously attacked in newspapers, by pamphleteers and printed art – such as works by cartoonist James Gillray. It was assumed that she had made a mercenary choice in opting for the man who could raise her social standing, rather than staying with the father of her children. She was considered to be a woman of loose moral virtue as she swapped from one partner to another. Gillray’s caricatures were overtly vulgar and demeaning and fuelled the public appetite for news of the couple. Unfortunately for Dora, a euphemism for a chamber-pot at the time was a Jordan and Gillray used this to his advantage frequently, symbolising the actress as a chamber-pot. In one print, he portrayed Dora as a large chamber-pot with the Duke of Clarence’s head stuck inside a large vaginal shaped crack entitled Lubber’s Hole, Alias The Cracked Jordan. In another, again depicting a chamber-pot, this time under a bed, printed with the words ‘Public Jordan Open to all Parties.’ Publicly ridiculed, William and Dora grew closer and waited for the storm to pass.

Gillray’s scandalous print

Gillray’s scandalous print

In January 1794, Dora gave birth to a son, baptised George FitzClarence – Fitz meaning son of. Dora was frequently pregnant during the first five years of their relationship. Two more children were born and she had several miscarriages. In 1797, William was surprised to hear from his father, who offered him the post of Ranger at Bushy Park. This role included Bushy House, a mansion set inside Bushy’s thousand acres of parkland. It proved the perfect family home for fifteen years. More children would be born to the couple, ten in all. Gillray still lampooned them, but there was a respect shown towards Dora now, as the Duke’s unofficial consort. The Duke would be mocked for being a stay-at-home father while Dora worked on the stage.

In the autumn of 1811, echoing her father’s treatment of her mother, William, Duke of Clarence, ended their relationship after 20 years of devotion from Dora. The Duke never managed money very well and was permanently in debt, this coupled with the beginning of the Regency, when the old King was declared mad and the family power finally landed at the feet of the younger generation (who were now middle-aged men), pressure was placed on William to marry a rich princess, or at least an heiress. Dora was devastated by the separation and William was mocked in the press for proposing to a woman half his age, and when rejected, chasing after several more. He arranged a regular stipend for Dora and for the care of the children, on the condition that she quit the stage. Having worked relentlessly, even when pregnant, it was odd that now was the time for her profession to be a problem.

Plaque at Cadogan Place, Chelsea

Plaque at Cadogan Place, Chelsea

Sadly, her own finances had dwindled through supporting her adult children and their spouses, and she was compelled to return to the stage in 1813 to pay off debts a son-in-law had run up in her name, reducing her allowance and her time with her children. But her earning power was a fraction of her younger years and she couldn’t keep up with the creditors. Eventually, in December 1815, she travelled to France to escape them. She settled in Saint-Cloud, where on 5 July 1816, she died. Strangely, on 1 July The Times in London announced that her death occurred on 27 June and had to print a correction on the following day.

Posterity will remember Dora for her stagecraft and she will also be remembered for her twenty year love affair with the Duke of Clarence. She bore him ten illegitimate children, all the while a working mother, acting in London’s theatreland as her pregnancies progressed. William, who in his dotage would be the last Hanoverian male monarch when he ascended the throne on the death of his brother, George IV, barely spoke of her to her children, but commissioned a marble statue of Dora holding two of her babies, which now resides in Buckingham Palace as part of the Royal Collection.

Memorial dedicated to Mrs Jordan

Memorial dedicated to Mrs Jordan

The Children of William, Duke of Clarence and Dora Jordan

George FitzClarence (1794-1842)

Henry FitzClarence (1795-1817)

Sophia FitzClarence (1796-1837)

Mary FitzClarence (1798-1864)

Frederick FitzClarence (1799-1854)

Elizabeth FitzClarence (1801-1856)

Adolphus FitzClarence (1802-1856)

Augusta FitzClarence (1803-1865)

Augustus FitzClarence (1805-1854)

Amelia FitzClarence (1807-1858)

Advertisements Share this:

- More