I was the only person in the house, who steadily professed good principles, habitually spoke the truth, and generally endeavoured to make inclination bow to duty; and this I say, not of course in commendation of myself, but to show the unfortunate state of the family to which my services were, for the present devoted….she [Rosalie] had never been perfectly taught the distinction between right from wrong; she had, like her brothers and sisters, been suffered from infancy, to tyrannize over nurses, governesses, and servants; she had not been taught to moderate her desires, to control her temper or bridle her will, or to sacrifice her own pleasure for the good of others…

On the one hand, Agnes Grey is a simple story about a daughter wanting to help her family when her father’s finances go wrong. Taking a position as a governess, Agnes reasons, will allow her to send money home. On the other hand, I found the book to be a complex account of the clashing of classes, in what constitutes love and marriage and the raising of children, and what makes a moral person.

When 18-year old Agnes leaves home to become a governess, she is leaving a loving, safe environment. She is naïve of the world outside her small village and is full of idealized fantasies that her new life will bring which will be full of good little children and her power to mold them.

But the reality is a shock to her system. The young Bloomfields run wild and have no use for her. To complicate matters, Mrs. Bloomfield has given her strict instructions that she must not discipline them in any way either through strong words or physical punishment. Agnes must do the best she can with the children without parental interest in their instruction or in her as someone they must respect. When the father does take an interest in his children it is through harsh punishment which makes Tom, the oldest boy, fear his father, which he takes this out on his sisters and to Agnes’s horror, small animals. She has no authority to chastise him and when she realizes his father condones this sadistic behavior it is a lost cause. In the classroom, Agnes spends more time chasing the children into their chairs, trying to interest them in anything remotely having to do with studies and generally throwing her hands up as they run out the schoolroom door.

It comes as no surprise to Agnes that she is finally dismissed because ‘she is not giving the children what they need,’ as though parental neglect and a refusal to see their children as they truly are had nothing to do with Agnes’s difficulty with them.

Agnes next finds employment at the wealthier Murray estate. Soon after her arrival the sons are sent to boarding school, so her main charges are 14-year old Matilda, the tomboy, who would rather be helping out at the stables or hunting with the dogs and 16-year old Rosalie who is almost ‘finished.’ Agnes’s instructions with the girls are similar to the ones she was given at the Bloomfields regarding punishment, with the added,

“only to render them as superficially attractive, and showlily accomplished, as they could possibly be made without present trouble or discomfort to themselves; and I was to act accordingly—to study and strive to amuse and oblige, instruct, refine, and polish with the least possible exertion on their part, and no exercise of authority on mine….And make them as happy as you can….”

One of the striking aspects of this book seems to me is a commentary on the upper classes and their frivolity and selfishness, their lack of discipline and moral standards in contrast to the upholding of the working classes as the real bedrock of Christian morality and virtue. Agnes grew up a clergyman’s daughter and her mother modeled for her and her sister all the important values missing in the homes of the upper classes at which she works.

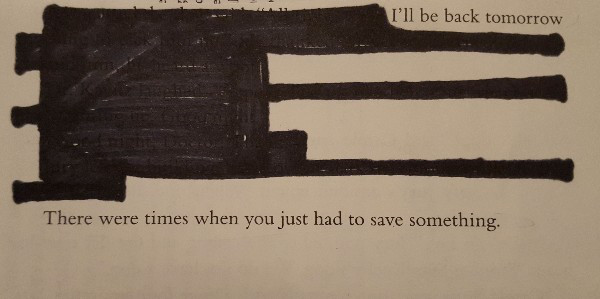

When the Murray daughters visit the cottagers on their estate they do so with irresponsible condescension and the mocking of the sick and poor to their faces. When they break their promises to return to read or visit with them, Agnes takes on this role. The girls did not learn from their parents what their status obliges them to do toward the poor and how to show sincere kindness to others. It is left to Agnes to be the example for them, though it seems to have no effect over the superficialities that take precedence over their lives.

This superficiality is never more striking than in the way Rosalie approaches marriage. She will, of course, marry for wealth and position as her parents see fit. Love is not a factor, nor is Rosalie’s own choice. Agnes watches with grave concern as Rosalie, in acts of rebellion, flirts mercilessly and leads men on, even toward a marriage proposal. It is almost as if she must prove to herself that though the choice of a husband is made for her, she herself could attract any man she wanted. She is mean with her selected prey, almost torturous and not concerned about the devastating hurt she is causing even after Agnes’s warnings.

This book, by the youngest Bronte sister, is often panned or looked upon as a more juvenile effort than her sisters’ books. But there is a wealth of commentary to be gleaned from Agnes’s thoughts and experiences about the intimate life of the upper classes. It is an eye-opening look at the snobbery, the self-importance and dysfunction of that class of family life. Children are left to their own devices by parents who give them over to governesses and nurses who have no power to truly educate or form them. For these twice on Sunday church goers, it is all for show.

Through Agnes’s selfless actions and comforting words with the cottagers and in the cottagers deeds to each other, the reader sees it is the middle and working classes who demonstrate the true teachings of the church, who come to each other’s assistance regardless of what little they have themselves. It is they who make excuses for the bad behavior of the upper class girls. It is in the morality of these classes that fidelity is shown to their husbands and wives, and children toward their parents and in the mutual aid of the cottagers toward one another.

The novel contains more plot lines than I have discussed here, including a happy romantic ending for Agnes and for her widowed mother with whom they both open a school for girls that becomes successful. But it is the issues above that captured my attention in this first reading of Agnes Grey.

__________________

My Edition

Title: Agnes Grey

Author: Anne Bronte

Publisher: Barnes and Noble Classics

Device: Paperback

Year: 2005

Pages: 224

Full plot summary

Challenges: Classics Club Spin #16, Classics Club List, Mount TBR, Library Love

Advertisements Share this:- More