I don’t know if I’d call myself a fan of Steve Gerber, but I am certainly interested in his work and his legacy in the field of comics. To be honest, however, in the process of doing “If It WAUGHs Like a Duck,” I came to dislike what I identified as his voice in the comic, and even as I lauded Colan’s art month after month, I found something off-putting in Howard the Duck’s politics nearly every time. Despite that, I was willing to go on a lot longer with that series. If the Chip Zdarsky and Joe Quinones version of Howard the Duck I was reading in conversation with the Gerber original had not ended after only 16 issues (over two volumes…sigh) I might still be doing it. I liked the discipline of the project, the need to sit myself down and read two comics every month and then write about them. The problem was the open-endedness of the project, and the reliance on the contemporary series lasting at least as long as the original. The former meant I sometimes grew tired as I imagined continuing for another year or so, and the latter meant that the very “reading a pair of comics in conversation” conceit was always in danger of collapse (and it eventually did).

This new project seeks to mitigate those factors somewhat by choosing two already complete comic book series: both version of Omega the Unknown. The more contemporary version has a definite and scripted ending, while the original had to be tied up by a different creative team after being abruptly cancelled. This wrapping up was not to the satisfaction of the original writers or (from what I can tell) many fans. Omega the Unknown, written by Steve Gerber and Mary Skrenes, with art by Jim Mooney, only lasted 10 issues, ending in 1976 due to low sales (exactly how low turns out to be information that is nearly impossible to determine). Gerber was fired before he could provide the promised ending in the pages of Defenders (which he had also been writing at the time), so the job of wrapping up was handed over to someone else. There were bitter feelings about the whole situation.

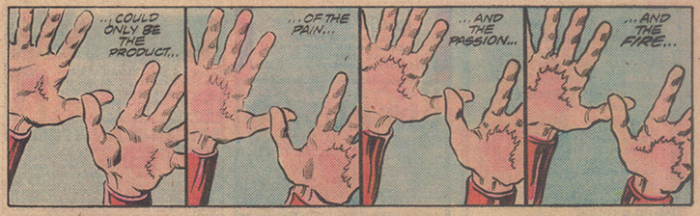

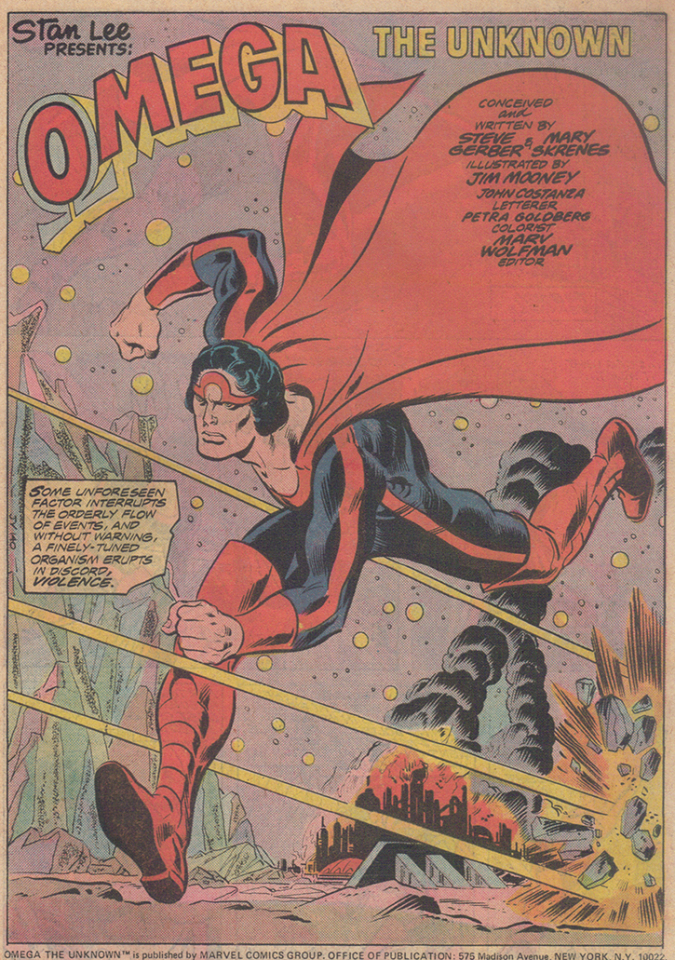

(from Omega the Unknown vol. 1, #1 – art by Jim Mooney)

Those bitter feelings came back to surface 28 years later when it was announced that Jonathan Lethem would be revisiting the series for Marvel, with the help of artist Farel Dalrymple, and co-writer Karl Rusnak. Gerber and (to a lesser degree) Skrenes objected to the revival, and felt that no writer or artist with integrity should take work using someone else’s characters without permission. Of course, Marvel would say Omega and his supporting cast are their characters to do with as they please, but the ownership of characters is the crux of Gerber’s conflict with Marvel.

In time, Gerber would come to soften his opinion of Lethem personally, but nevertheless did not favor Marvel reviving Omega the Unknown for even for a 10-issue limited series that was distinct from the Marvel Universe. I think Gerber’s initial reaction was based on his assumption that Marvel was just out to screw him, and anyone working with what he considered “his characters” was screwing him over, too. Skrenes, on the other hand, felt she understood Lethem’s motivations from the beginning. Gerber reports her as trying to convince him that:

When courted by the comics publishers, [Skrenes] believes, [‘name’ writers from the mainstream] suddenly revert to the mindset of every fan writer and artist who ever dreamed of becoming a comics pro. They mindwarp back to their own age of innocence, to the time when they first discovered the comics they loved, comics that perhaps inspired them to create stories of their own. Blinded by love and desire, Mary believes, they happily sign the work-for-hire contracts and giddily appropriate the work of other creators with the unquestioning enthusiasm of adolescents engaging in unprotected sex.

Skrenes’s perspective seems reasonable (if hyperbolic) to me, though I am not sure it actually applies to Lethem given that so much of his work takes up deconstructing the toxic nostalgia that often clouds our view of the complexities of lived experience. Omega the Unknown shows up as a thematic echo in Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude, and I imagine his interest in revisiting the comic book arose from a desire to play with the metaphor-made-literal in the form of this very strange set of characters. I must also admit that Fortress of Solitude is among my very favorite books, and it played no small part in reviving my interest in comics and leading down the path of being a comics scholar. So, returning to this series feels like a crucial site for where my interest in comics and literary fiction overlap.

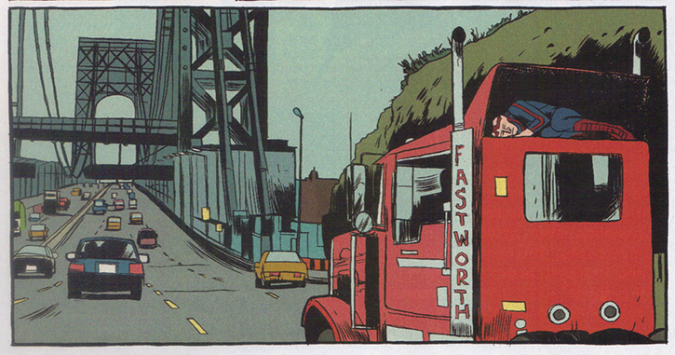

(from Omega the Unknown vol. 2, #1. art by Farel Dalrymple)

Unlike If It WAUGHs Like a Duck, which had me reading comics I was essentially unfamiliar with except in terms of the reputation of the original series, I have read all of the 2007-08 Omega the Unknown series, and have read individual issues of the original series (but not all) piecemeal over the years. Despite this, I still feel like I am coming to these pretty fresh because I remember few of the details of either, even though I have a better sense of the general arc of both series than I did with Howard.

The approach in this series of posts will be similar to as it was in the Howard the Duck series. Each installment will feature two issues, one from the original 1975-76 series and one from the 2007-08 series. I plan for 11 installments in total (the last covering Defenders #76 and 77, some scholarly views on Lethem’s work, and a general wrap-up). The format of each installment will put the two issues into conversation, consider how the latter re-imagines the former, consider what the original issue might have felt like to read when it first appeared on the stand, and how the re-make might be in conversation with Lethem’s other work.

The installments will also be significantly shorter than this one. So, let’s get the alpha to this omega going…!

Omega the Unknown Vol. 1, #1

Cover Date: March 1976

Release Date: December 23, 1975

Writer: Steve Gerber and Mary Skrenes

Penciler: Jim Mooney

Inker: Jim Mooney

Colorist: Petra Goldberg

Letterer: John Costanza

Omega the Unknown Vol. 2, #1

Cover Date: December 2007

Release Date: October 3, 2007

Writer: Jonathan Lethem w/ Karl Rusnak

Penciler: Farel Dalrymple

Inker: Farel Dalrymple

Colorist: Paul Hornschemeier

Letterer: Farel Dalrymple The Covers

The Covers

Looking at the covers of these two issues, my immediate preference is for the one by Farel Dalrymple in 2007. It presents clean centered action that perfectly captures the style and kinetic energy of the interiors. On the other hand, the blank background and the generic robots Omega is fighting on the cover makes it verge on boring. The original issue cover, with art by Ed Hannigan and Joe Sinnot, is a lot busier. The yellow background makes the details in the upper half of the cover look unfinished or even un-inked, and while I typically like text on comic book covers, the text in the black caption over the purple robot’s head is misleading about the tone of the book. I do like the text superimposed on black arrow in the bottom left, as it more clearly establishes the mystery of the comic. I also like the details of the background, the breaking glass, the Amazing Spider-Man comic on the bed, the medical chart. I am also a sucker for the old time corner art, and this one—with Omega and James Michael Starling’s slightly overlapped faces—suggests a Billy Batson/Captain Marvel Shazam!-like relationship between them, though soon we will see they do not really have one.

The Issues

I may be going out on a limb here, but based on one issue of the original Omega the Unknown, I want to claim that while Howard the Duck is frequently considered Gerber’s legacy, Omega is immediately and obviously notable as a better comic book. I wonder if this had to do with the influence of Mary Skrenes, and/or working with Jim Mooney, but I was drawn in immediately. Sure, the narration can be a bit over the top, a little too earnest, but I don’t mind that in the comics of the era. The use of captions in place of thought bubbles (which don’t make an appearance in the whole issue) gives the comic a more modern flavor despite the overwrought prose. Such a strategy was not common to comics of the era and would not become the norm until sometime in the 1990s. And the prose, for its flaws, does captures a sense of the inscrutable obsessive self-reflection of adolescence that the book seeks to evoke. It works.

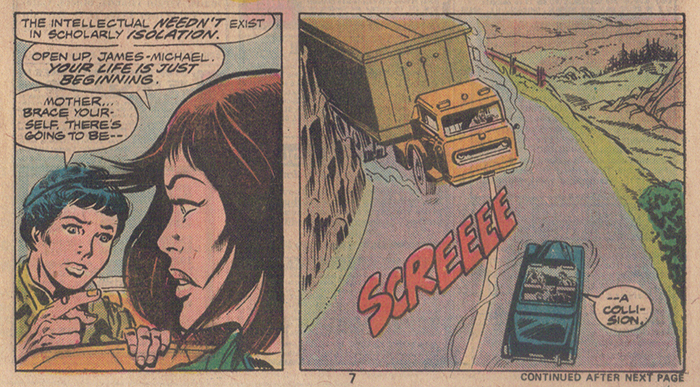

James-Michael Starling seems to predict the coming collision.

Omega the Unknown vol. 1 begins in media res, with our titular silent hero running and leaping. There is little to explain exactly what is going on. Instead, we only know the familiar basics of the sci-fi origins of the Superman superhero type. Omega (as we shall call him for lack of a better name) flees robotic villains on some distant planet. He is “the last of his superior breed.” It is a riff on Krypton, but colored with the impassioned mystery of our silent hero. Everything seems painful to him, to fight, to flee, to manifest the gouts of energy that erupt from his omega-marked hands, to simply be. The connection with precocious James-Michael Starling is immediately apparent. As the sci-fi superhero is shot down, the young boy jolts awake in fear and pain, to be awkwardly comforted by his parents. The events we’ve seen depicted were his dreams. Or were they? The pain he feels through the mysterious connection to the figure he dreams of is quickly forgotten, however, in favor of the more immediate adolescent pain of his circumstances. Home-schooled and solitary by nature, James-Michael Starling chafes at his parents’ choice to move him from their isolated mountain home to the city in order to go to a special school and be among people his own age and learn some of the social acumen his seems to lack.

James-Michael Starling is not like other children.

There is something about James-Michael’s affect that suggests severe challenges to his social development. He wants to avoid interactions with peers, but he discusses it with bookish detachment that suggests his simultaneous awareness of the complexities of the social world, and anxiety about dealing with the unknowable messiness of people. This sense of his atypical socialization is reinforced not only by his vivid dreams, but in one set of panels he seems to have some kind sixth sense or foresight, as he predicts there is about to be a car crash, and then there is. His parents are killed in the crash, but not before James-Michael learns they are robots, their dismembered bodies melting away in the fire of the collision. We are only six pages into this comic book at this point! His mother’s melting head gives him a final warning, explaining “The world may confuse you…but you’ll be all right…Only the voices can harm you…Don’t listen to the voices…” It is a powerful and whacked out scene that ends with James-Michael collapsing in shock as he begins to hear whispers that turn into “roars.”

What are the voices? We don’t know.

Of course, the metaphor of discovering that your sense of displacement might have something to do with the fact that you were raised by robots is one that works with the anxiety of adolescence, and its fantasies of learning something special about ourselves that sets us apart, even as we want nothing more than to fit in. In the 1970s Omega the Unknown, James-Michael Starling is only 12 years old, his equivalent in Lethem’s 2007 version is 14, which seems more appropriate for the adolescent metaphor. Rather than warn of “voices,” the 2007 robot mom responds to his confusion by noting it is a common human sentiment. She asks him to promise to accept the help of the people he meets. “You’ll need it,” she adds. Social and emotional intelligence remain lessons he can only learn by being in the world. He also falls into a coma and is carted off to a hospital by the authorities.

In 2007, James-Michael Starling is called Titus Alexander Island (Alex for short), and Dalrymple draws the panels leading up to the crash to make Alex’s warning about the collision less ambiguous. He simply sees the truck in front of them jackknifing. It is, however, an example of how throughout the re-telling Lethem and Dalrymple riff directly off the original, including panel layout.

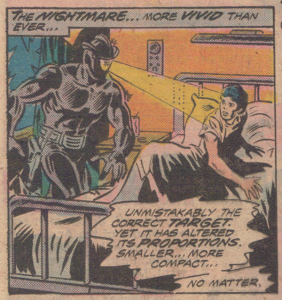

Most of the plot of both issues revolve around our young protagonist in a coma, and a young nurse’s obsession with him. Interspersed in both are scenes of Omega the Unknown, now on Earth (in Lethem’s version we never see him on another planet, merely camping out in the woods), discovering and silently fighting robots. Eventually he traces the robots to James-Michael/Titus Alexander’s hospital room (well, one robot in 1975, two in 2007), where they mean to do the boy harm. In 2007, while Omega defeats one of the robots, the other get the drop on him. In 1975, the one robot is just that tough. In both, it takes the boy’s sudden manifestation of gouts of energy from his hands to rescue the silent superhero from the assailants. The boy is also confused, having dreamed of Omega, but not knowing who he is. In the Gerber and Skrenes version, the killer robot also seems confused. It identifies the boy as their target (Omega), but does not recognize his form. It must “re-evaluate” when the actual Omega arrives. The narration in both also suggest slippage between Omega and the boy’s consciousnesses when in each other’s presence. This is a lot more pronounced in the 70s version where the narration explains when the fight is over that James-Michael is able to “distinguish his own thoughts, his own sensations once again.”

Both issues have the same two final panels. The doctor attending to the boy (Dr. Barrow in 1975, Dr. Desani in 2007) comes to find out what the ruckus is about, and discovers the kid in agony, the Greek letter Omega seared onto the palms of both hands and still smoking. The doctors think the boy may have harmed himself (no one having seen Omega or the robots who slipped off), the boy’s social awkwardness being interpreted as a sign of deep psychological distress. Each version of the boy, however, remains strangely detached from his experiences. He has a flat affect no matter what is happening that is only belied once in the 1975 Gerber and Skrenes version, and not at all in the Lethem one.

The final panels of both Omega the Unknown vol. 1 #1 (above) and vol. 2 #1. (Art by Jim Mooney and Farel Dalrymple, respectively)

When arrangements are made for Ruth Hart, the nurse that has taken a deep interest in James-Michael, to become his guardian, her roommate Amber comes to the hospital to meet the boy. After meeting Amber, James-Michael is unable to sleep. He feels “aglow” thinking about her, and clearly is experiencing his first crush. In 2007, there is no Amber. The nurse’s name is Edie, and Amber is replaced by Clare Weiss, who appears to be some kind of social worker, who lives near, but not with, Edie.

Turns out Ruth, in the 1970s version, is the only element in the issue that links it to the wider Marvel universe (save for the issues of Spider-Man on the cover), as she first appeared in Man-Thing #2 in 1974 (also by Gerber), where she was a hippie-ish hanger on with the Skull-Crusher biker gang.

Nurse Ruth Hart and Dr. Barrow (from Omega the Unknown vol. 1, #1)

Both Ruth and Edie are strange figures, sheepish and sensitive women that, despite their professional position, seem coddled and even infantilized by the people around them. In the Gerber/Skrenes version, Ruth is desperate to get close to James-Michael, not only for herself, but at the behest of Dr. Barrow who is concerned the clinic board won’t pay for the kid to stick around and be studied. The hope is she will learn something about his case that will make it of interest to the research curiosities of the powers that be. It is when this fails, the plan is adjusted to have James-Michael move in with her and Amber. In the Lethem/Rusnak version, the narrative makes sure to paint Edie as naïve, and a recent arrival in New York City from Oklahoma. She has a natural rapport with James-Michael, and Dr. Desani even suggests that the reason social worker Clare Weiss is setting up Edie as Alex’s ward is as much for the nurse’s benefit as for the boy’s. There is something about both versions of the nurse character (but especially the 70s version) that makes me think of the worst qualities of Beverly Swiztler from Howard the Duck.

The biggest difference between the two volumes of Omega the Unknown is the inclusion of a character called “The Mink” in the latter version. The Mink is a corrupt and mercenary superhero type, working with the Mayor and the DA, taking credit for stopping crime when convenient for them, but also falsifying documents in order to cover up what really happened in the car crash. He’s a publicity hound, and wants to make sure he is always making the biggest headline. In 1975, the robot bodies of James-Michael’s parents melted away before anyone saw, so Dr. Barrow and others are skeptical of the boy’s claims that they died in the crash. There is no evidence anyone else had been the car, making the whole thing a mystery. In 2007, the police and the Mink find the robot head, and it is in trying to plug it and make it work that it fries and melts away. The Mink is clearly meant to be an arrogant scumbag. He condescends to the cops, bullies the mayor, and is depicted working at a laptop surrounded by surveillance monitors while luxuriating in a hot tub. He drives around in a truck plastered with his name and face, and has a creep cop on his payroll who peeps through Edie’s window and watches her undress. Titus Alexander Island remains a mystery in this version, but someone knows the connection between him and robots exists, even though there is no public record of the boy or his parents existing. In 1975, no one knows anything about him.

Robots arrive looking for Omega and find James-Michael Starling.

As for the art, I don’t know much about Jim Mooney, except he had a long history at DC Comics, inked some Spider-Man comics for Marvel, and penciled the entire run of Omega the Unknown, and inked a bunch of it himself. The art and panel layout in Omega the Unknown volume 1, #1 is fantastic. It has both a kinetic feel to the action and a pensive and patient feel in panels where characters and plot are developing. Petra Goldberg’s colors help a whole lot, too. Farel Dalrymple, on the other hand, has a very distinctive style that I cannot imagine cutting the mustard in the days of 1970s Marvel house style, but that works perfectly in the 00s to make the new Omega the Unknown look distinctive, and evoke an indie comic feel (which makes sense given Dalrymple’s indie bonafides). The first three pages are made up of nothing but those page-wide faux-cinematic panels that I tend to hate (but do not recall being tired of in 2007), but after that the paneling becomes more varied as to actually develop a sense of visual rhythm. I appreciate a unified art style and the choice of an artist who has hardly done any work for the Big Two, which allows for this work to stand out. He clearly studied Mooney’s work in the original series and riffs on exact panels and layouts in many places. I look forward to seeing the art in both books develop as I read them.

The Eschatology of Omega

In reading and re-reading both versions of Omega the Unknown #1, I can’t help but wonder if Lethem did his best to respect Gerber’s wishes. When Gerber wrote about the Omega the Unknown project on the Yahoo! Howard the Duck forums, he directly addressed the novelist after he’d had a chance to talk it over with Lethem. It was reported later on by Comic Book Resources:

“Jonathan, if you’re reading this — rather than ask you to back out of a business commitment, rather than deprive the fans of what will probably be an excellent story, I propose that you simply retitle the story and rename the characters. ‘Omega the Unknown’ has little or no commercial cachet, so call the book something else. Call the kid something other than James-Michael Starling. Make the book your own, and I’ll have nothing to complain about.”

While I cannot imagine that changing the name of the series was ever an option, Lethem’s version of Omega the Unknown nevertheless does change all the names of the characters, adds new characters (like Clare and the Mink), and while it visually riffs off the original series, does not make any explicit reference to it in the text. As I continue to read both series, we shall see to what degree this remains the case. It is certainly true (from what I remember) that the Lethem version does not crossover with (or seem to exist at all within) the greater Marvel universe. The Gerber and Skrenes version, on the other hand—in addition to using a character from Man-Thing—advertises an appearance of the Hulk coming up in issue #2.

The robots in the 2007 version of Omega the Unknown do not speak.

While I really love Farel Dalrymple’s art, and Lethem’s prose avoids the over-the-top approach of Gerber’s captions, I have to say that between the two first issues I enjoyed the 1975 version more. It must have been a strange issue to read back in the day. So unlike the rest of what was going on in the Marvel Universe at the time. The 2007 version was only interesting to me in terms of how it plays off and within the framework created by the original. I am not saying it is bad, but on its own, I am not sure how compelling it’d be for an unfamiliar audience. The fact that the re-make only sold about 10k issues in the first month, and would eventually drop below an abysmal 7000 issues before ending seems to suggest not only that Gerber was right about the property not having much cachet, but also suggests that his concern about the outcome of the series and its overwriting whatever value Omega the Unknown might have was misplaced. Ultimately, it made no difference to Marvel’s bottom-line or Gerber’s legacy.

Unlike my series on Howard the Duck, I think I am going to have a harder time holding off on reading through these comics. I mean, when I did If It WAUGHs Like a Duck I had to wait for each of the Zdarsky/Quinones issues to come out to read the Gerber/Colan ones along with it, but HtD never captured my imagination enough to make me very eager to continue and feel anxious about the wait. Now, I have to hold off from reading through them all in one afternoon so they might stay fresh and individual in my mind and capture the immediacy of my reading as I write up each of these installments. If issue #1 is anything to go by, maintaining that patience is gonna be hard.

Index | Next

Index | Next