American Splendor (2003)

Dir. Shari Springer Berman, Robert Pulcini

Written by: Shari Springer Berman & Robert Pulcini (based on the comics by Harvey Pekar)

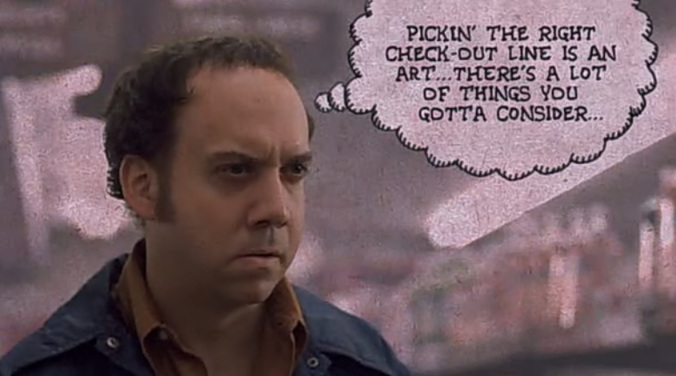

Starring: Paul Giamatti, Hope Davis, Harvey Pekar

American Splendor is a biopic about the life and work of Cleveland cartoonist Harvey Pekar, the creator of the comic series of the same name. The comic “American Splendor,” which ran from 1976 to 2008, follows the mundane everyday lives of Pekar and his friends and coworkers. It contains Pekar’s musings on life and is presented in his cynical, often miserable, tone, with the illustrations being provided by some of the biggest underground cartoonists of the 70s and 80s. The film adaptation is a genre-hopping picture that presents primarily the period of Pekar’s life in which he was writing the series. It intertwines a dramatized version of Pekar’s life in which he is played by Paul Giamatti with interviews with the actual Pekar, his wife, and friends. Many scenes from the film are direct adaptations of panels from “American Splendor,” sometimes even fading in or out from the illustrated panels.

I have fond memories of this film, having seen it shortly after its release, sometime in 2004. I wasn’t familiar with the comic series at the time, but I remember liking the film’s style and being very enamored with Pekar as a character, both through his actual interviews and Giamatti’s portrayal. I identified very much his persistent negativity. The documentary aspects of the film lent the dramatized storyline veracity, and I enjoyed watching Pekar be interviewed with Giamatti sitting in the background. The film goes out of its way to highlight its construction, which was intriguing to me. I liked being able to compare Giamatti’s performance with the genuine article. I was also intrigued by Pekar’s brand of blue-collar intellectualism. I probably watched the film a half dozen times between 2004 and 2007, or so.

I was disappointed that after not having seen it in probably a decade, American Splendor didn’t live up to my memories. The film’s varied style of presenting its story, an aspect of it that I had previously enjoyed, was the primary reason for me not connecting with it this time around. Stylistically, I was fine with the introduction of animation and panels from “American Splendor” in the narrative portions of the film, but I felt that the documentary and narrative portions just didn’t mesh. I think that American Splendor works better as a documentary that it does a narrative film, and the presence of the actual Harvey Pekar overshadows the film’s narrative. Springer Berman and Pulcini use Pekar as a narrator throughout the film, both in voice over and in filmed interviews. His character and commentary are so engaging that I found myself wanting more of that, which took away from the film’s narrative segments. I felt that there were the makings of a very good talking head style documentary and a pretty good comedic biopic contained with American Splendor, but I couldn’t quite reconcile the two into a greater whole.

I’m not surprised that the documentary portions of American Splendor shine through, because the film is Springer Berman and Pucini’s first foray into narrative cinema. Previously they had directed several documentaries, primarily about Hollywood subjects. The husband and wife team craft the narrative well, however, and the film, which was shot on location in Cleveland and its suburbs, feels authentic. Giamatti’s performance also helps to elevate the film’s narrative portions, as he captures Pekar’s essence perfectly. He embodies Pekar’s pessimism with his hunched, shambling gait and his raspy line delivery. This role was one of Giamatti’s first breakthrough performances, and it’s clear why he gained the acclaim he did for it. A lesser talent would probably not have been able to stand up in the shadow of the charismatic and funnily sardonic Pekar. My biggest complaint with the narrative portions of the film is that the narrative often feels directionless. I don’t know if this was a conscious artistic decision to mimic the slice of life style of “American Splendor,” but the film felt lacking in motivation. It was enjoyable to watch Giamatti growl and mutter his way through the film, but outside of some occasional domestic turmoil with his wife, Joyce (Hope Davis), there was very little narrative tension or conflict. The film’s third act focuses on Pekar’s diagnosis and subsequent battle with lymphoma, but it feels more like an epilogue than a continuation of the story that the film had previously been telling. Pekar beating cancer should feel like a narrative payoff, a big win for the hero of the story, but instead it had the same significance of any of the other events depicted in the film. I don’t mean to sound overly critical of the film, because it is enjoyable enough. I do think it would have worked better as a documentary with inserts from Pekar’s cartoons and many media appearances. As it is, American Splendor feels a bit like a jumbled mixed-media collage. I think there could be many reasons for this stylistic choice, but it ultimately doesn’t work for me.

While I likely won’t be rushing to watch American Splendor anytime soon, rewatching it has made me realize how influential the film was in developing some of my literary interests without me even realizing it. A few years after moving to Pittsburgh, I was finally able to track down an “American Splendor” anthology at my local library, which I eagerly read and thoroughly enjoyed. From there it was a short leap to discovering the novel Post Office, and Charles Bukowski became one of my favorite writers during my early- and mid-twenties. In the years after dropping out of graduate school, I sank myself into my work as a bartender and I had a lot of trouble reconciling my professional career with my latent desire to continue academic or creative pursuits. In Bukowski and Pekar, though I didn’t realize it at the time, I had found kindred spirits. Working class intellectuals who created great art not in spite of their circumstances of employment or their lack of formal training, but because of it. I don’t have anywhere near the talent of these writers, but it’s good to remember that it’s never too late to get started again. Though Bukowski eventually left his job at the post office, he didn’t become a full time writer until his forties. Pekar worked as a filing clerk for the Cleveland VA hospital for nearly 40 years, finally retiring in 2001, well after he had received much acclaim and fame for his writing. It’s impossible to imagine the work of either without their professional experiences and working class sensibilities. I haven’t thought about Harvey Pekar or American Splendor in years, but his depictions of the day-to-day lives of everyday people, and his elevation of their mundane existences to poetry, have stuck with me and shaped the way I interact with the world today.

Share this: