Inside The Great Pyramid, Giza, 2017 (c) LPOBryan

I visited the Great Pyramid of Giza in February, 2017. The passages inside were very different to what I had imagined. They were smaller and narrower. But the Grand Gallery, shown above, is a stunning space, which we still don’t understand.

It’s located in the center of the pyramid and leads to the King’s Chamber, the location of a number of scenes in The Cairo Puzzle. See its location below.

What interested me most was the possibility that the Grand Gallery was a scared space used for the recitation of hymns by the ancient Egyptian priesthood. The space echoes wonderfully. It would have been a powerful place in which to recite hymns.

If this was the case, the Cannibal Hymn is likely to have been recited there.

Appearing first in the Pyramid of Unas at the end of the Fifth Dynasty, the Cannibal Hymn preserves an early royal butchery ritual in which the deceased king slaughters, cooks and eats the gods and others, incorporating into himself their powers.

The style of the Cannibal Hymn is characteristic of the recitational poetry of pharaonic Egypt. This will give you a taste of what the Cannibal Hymn was about:

A god who lives on his fathers, who feeds on his mothers… Unas is the bull of heaven Who rages in his heart, Who lives on the being of every god, Who eats their entrails When they come, their bodies full of magic From the Isle of Flame…The cannibal hymn also rappeared in the Coffin Texts as Spell 573. Here’s a few more lines:

Unas is he who eats men, who lives on gods, lord of messengers who gives instructions. Indeed, Khonsu (the Moon), who slaughters the lords, cuts their throats for Unas, and takes out for him what is in their bellies. He is the messenger whom he sends out to chastise. Indeed, Shesmu (Wine-press god) cuts them up for Unas and cooks for him a meal out of them in his evening cook pots. Unas is he who eats their magic, who swallows their spirits. Their great ones are for his morning meal, their middle-sized ones for his evening meal, their little ones for his night meal, their old men and the old women are for his fuel..

You get the idea. Some translators have claimed that this refers only to Unas eating gods, but the ritual seems to go further than that for me.

Which got me thinking. Where did the early Christian fathers get the idea of Christ’s body and blood being given out to all those who attend Mass? Isn’t there an echo of our cannibalistic past in this central Christian ritual?

Christ himself is believed to have spent his missing years in Egypt. If so, that may have been where he learned his magic, turning water into wine and raising the dead. Egypt was the home of ancient magic and a place of great medical knowledge. Roman Emperors wanted their physicians to be Egyptian.

Galen, one of the most influential physician in history, who helped the Empire deal with the Antonine plague studied at the great medical school in Alexandra. Hippocrates (the “father of medicine”), studied at the temple of Amenhotep, and acknowledged the contribution of ancient Egyptian medicine to Greek medicine.

That Christ learned how to heal the sick in Egypt is a perfectly reasonable proposition. That his followers adapted the ideas of the Egyptian priesthood, including the mythic symbolism of eating a part of a god to have something of that god transferred to you, is also very reasonable.

Whether the ancient Egyptians priests were also cannibals is open for debate.

Some early dynastic depictions of sacrifices have been found, showing a man holding a bowl, possibly using it to catch the blood of a victim who is seated in front of him. The man and the victim are normally before either gods or men of power, making it seem as if these scenes are of human sacrifices. Despite the pictures, there is not enough information as to why it was done, what happened with the blood in the bowl, or for whom it was done.

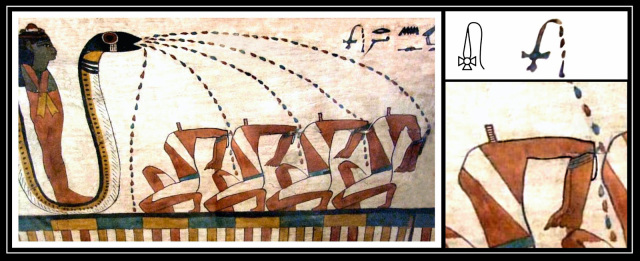

Surgically beheaded captives, painted panel, the Louvre.

For further evidence, the above image shows a Pharaoh, as Osiris, riding a python, and spitting fire at four captives whose heads have been surgically removed. Neck vertebrae extend from the headless enemies. The flaming breath which consumes the torsos is represented by the surgeon’s symbolic alternating red and blue drops of blood and water.

A key is found in the stylized ideogram in the upper right corner of the scene, enlarged in the upper right pane. This hieroglyph is in the form of a cooking brazier–a portable oven with a flame issuing from the top. The glyph is also used in words about cooking foodstuff.

So, we have pictorial references to the eating of human flesh, and literary references. The question is, how does this all relate to The Cairo Puzzle? Well, here’s the thing, the Great Pyramid still holds secrets. The parts that we know inside represent only a small part of what the ancients described as being inside the great pyramid.

Historical commentators, such as Manetho and Plutarch, claimed that a Hall of Records, under the area of the pyramids at Giza, housed written records of the founders of Egypt. And records of ancient cities that came before, and of how the larger pyramids were constructed.

If the Hall of Records contains such records, it will also contain more details of the uses of the Cannibal Hymn.

As the Cairo Puzzle opens, Isabel Ryan travels to the city in search of Sean, her husband, who went missing, presumed dead, at the end of The Nuremberg Puzzle. The first place she looks for him is in a hospital.

To find out more stay tuned. The Cairo Puzzle will be released in July, 2017.

Advertisements Share this:- More