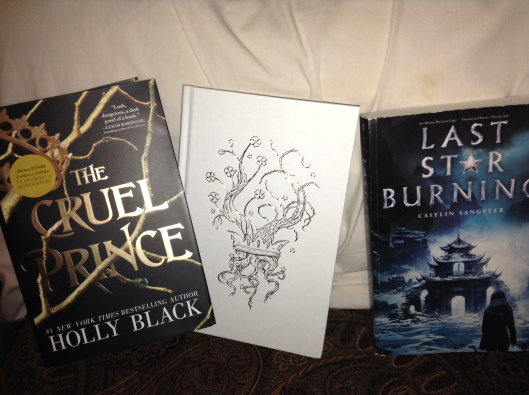

Holly Turner in The Testament of Mary, Northern Light Theatre. Photo by Ian Jackson.

By Liz Nicholls, 12thnight.ca

In the absorbing Northern Light Theatre season opener, a woman peers out at us warily through the twinkling strands of a light-up fence. We’re close enough for her to eyeball us; this is the tiny PCL Studio Theatre after all.

The barbed wire confinement of a history in the shadows? A star marquee? A prison masquerading as something else? In the course of The Testament of Mary, Colm Toíbín’s stage adaptation of his own provocative novella, we’ll be invited to wonder about all of the above. Mary does.

Trevor Schmidt’s cunning and beautiful set design for his production — with its looming, richly-hued panels and striking, meaningful lighting by Adam Tsuyoshi Turnbull — encloses a character from one of the world’s most influential stories. It’s one that’s given Mary a principle role she doesn’t want: mother of God. Mary’s a player all right, but she doesn’t want to play.

She’s a mother who has lost a son (she refuses to say his name). And filtering through endless grief, and the horror of his agonizing death by crucifixion, is a kind of simmering anger. Holly Turner’s multi-layered performance reveals all that, gradually — it doesn’t give up its secrets easily, without a struggle — in the course of this fascinating, and harrowing, extended monologue.

Holly Turner in The Testament of Mary, Northern Light Theatre. Photo by Ian Jackson.

Mary, as we meet her in Toíbín’s play is not the gentle beneficent Piéta central to Catholic tradition, a departure which has certainly generated controversy amongst the faithful. Nor is Mary, as we meet her in Schmidt’s production, a natural firebrand radical. Turner has a quieter kind of intensity, acid-tinged around the edges of what seems to be natural reserve. She conjures a kind of human-scale resistance fighter, living with terrible memories. In a universal story of extraordinary, contagious belief Mary is a skeptic.

She regards the apostles who come to interview her — she’s a prize first-hand witness for the gospels they’re writing — as guards not guardians. They’re cultists, in her view; they’re creating stories, mythologies, a new religion, and they have an agenda. What they need from her is compliance.

She takes a dim view of the disciples. Her son has been co-opted, by “a group of misfits,” she says, men without fathers, the kind of men “who could not look a woman in the eye.” They “roam the countryside in search of want and affliction,” she says sardonically. And they’ve wrenched her shy, sweet-natured son from her and set him up for catastrophe — as a preacher, a messianic miracle-worker, the king of the Jews, and even the son of God.

Mary is having none of it. “He could have done anything,” she says, tormented over the might-have-been. “He could even have been quiet.” The public voice she finds “all false … the tone all stilted.”

Mary was there for the celebrated miracles, the wedding at Cana where water was transformed into wine, the raising of Lazarus from the dead. And she regards these events warily. In the case of Lazarus, a friend of the family, though, there’s an undeniable tone of reluctant wonder in her account. It’s coloured with the lacerating knowledge that this disturbing power and fame comes with a fatal price tag in a world of power- and fame-seeking men.

Mary lives in her memory. The most terrible of all is the crucifixion. Turner’s performance gets quieter still, and gains dimensions as Mary revisits this “vast cruelty,” a drama played out on a deliberately public stage. From this memory, there is no escape; it’s Mary’s doom.

Turner roams the stage restlessly, in and out of shadows, like someone testing the perimeters of a very artful cage. And she replaces one shawl with another, a woman either trying out personas and rejecting them, or remaining in motion because she can’t bear to be still.

In the repertoire of “memory plays,” this one takes on a uniquely thorny (no pun intended) challenge. It stars a grief-stricken mother who’s been assigned a high profile, but silent, role in history, and doesn’t want it. She lives instead with anger and loss.

In her watchful, quietly fierce performance Turner makes us see the human cost of great earth-changing events.

REVIEW

The Testament of Mary

Theatre: Northern Light

Written by: Colm Toíbín

Directed by: Trevor Schmidt

Starring: Holly Turner

Where: PCL Studio Theatre, ATB Financial Arts Barns, 10330 84 Ave.

Running: through Nov. 4

Share this: