Hey, guys! Welcome back to another blog post! This time, I’m discussing archetypal literary theory and the role it plays in Robert Macfarlane’s The Wild Places. For those who don’t know, The Wild Places is a novel written about the author and his journey to find the last remaining wild places of the United Kingdom. Although I’m only halfway through, I’d highly recommend that you give it a read!

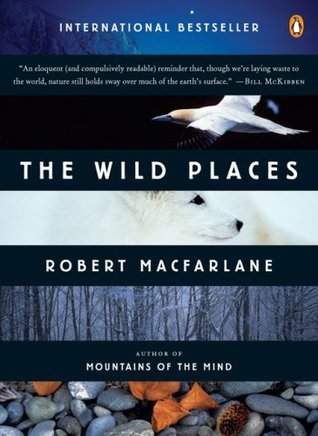

The Wild Places, Robert Macfarlane

The Wild Places, Robert Macfarlane

The main character in The Wild Places is the author himself, Robert Macfarlane. In the novel, Robert fits quite well into the archetype of the Hero. I say this because he is on a sort of quest, if you will, and feels the draw to go on the quest, like many heroes in other tales; “For weeks before the windstorm, I had felt the familiar desire to move, to get beyond the fall-line of the incinerator’s shadow, beyond the event-horizon of the city’s ring road.” (Macfarlane 10) Unlike many heroes, I would say, Macfarlane plans out his journey, “I listed hill-forts, barrows and tumuli in the Welsh marshes and the south-western counties, and plotted routes between them.” (Macfarlane 15). In my experience, most heroes start off with a rough idea of where they are, and where they want to go, then make up the in-between as they go.

Throughout his travels, Macfarlane both brings along with him different characters fulfilling the archetype of the Mentor, including his father and an old friend, but also gathers information from those he meets along the way. For instance, whilst exploring a river-mouth, he encounters a lumberjack by the name of Angus. Angus invites Macfarlane to come fishing with him the next day, to which Macfarlane agrees. It is when they are fishing that Angus points out “…the ruins of a nineteenth-century look-out point. [It was there that] [d]uring the spawning season, men would sit there watching for incoming shoals of salmon.” (Macfarlane 78). It is through the teachings of his companions that the author learns more about the wild places that he visits, and their histories. Gathering mementos and objects from the places of his travels also helps Macfarlane remember and learn about these places. It was from his parents, one of whom accompanies him on one of his travels, that he learned to do this; “My habit of gathering stones and other talismans was a family one. My parents were collectors. Shelves and window-sills in my house were covered in shells, pebbles, twists of driftwood from rivers and sea.” (Macfarlane 58)

There is also a fair amount of symbolism through things such as water and wood, in this book. For example, a piece of pine wood that Macfarlane picks up in the moor symbolises life, even after death in this case, since the wood is long dead; “I placed the pine fragment at the end of the loose line of objects, and it watched me with its knot-eye while I worked” (Macfarlane 58). Trees are very important in many cultures, often representing life, sometimes even people. For example, First Nations teachings “speak of trees as ‘The Standing People’.” (Touch Wood Rings 4). Pine, specifically, symbolises peace (Touch Wood Rings 9).

Knotty pine driftwood

Knotty pine driftwood

Water is also key in Macfarlane’s journey, being present in almost every location in some form or another. The many forms of water mentioned in the book, from sea to snow, from river to loch, show how water, archetypically, is used to symbolise rebirth. I think that, since Macfarlane mentions water so much, and that water is a symbol of rebirth, he is stating, albeit indirectly, that, although much of the wilderness of the United Kingdom has been lost today, he hopes that at least some of it will be able to reclaimed in the future.

Colours and the archetypes they represent are also mentioned frequently in this work. Macfarlane begins with describing the phosphorescence of the ocean off of Ynys Enlli, “I walked down to the edge, squatted, and waved a hand in the water. It blazed purple, orange, yellow and silver.” (Macfarlane 29).

Ocean phosphorescence

Ocean phosphorescence

The number of colours and their vibrance, I feel, symbolises the many wonders of nature, much like the colours of autumn leaves mentioned in numerous films and books, and how the different aspects of it can be the same, whilst other aspects remain different. Also mentioned in the book so far is the colour white, as in the snow found in the Black Wood, “A flake fell on the dark cloth fell on the dark cloth of my jacket, and melted into it, like a ghost passing through a wall.” (Macfarlane 60). The archetypical role of the colour white is to symbolise innocence, whilst dark colours, such as black, are used to symbolise darkness, chaos and upheaval. The fact that the white melts into the dark is representative of the white innocence of the woods and the wild melting into and being absorbed by the dark human machine.

As I hope I’ve made clear to all of you, there are quite a few good examples of archetypes in The Wild Places, at least in the first half. I encourage you all to look into it a bit more, maybe even read it! Just in case there are a few of you out there who will take me up on that, I’ll try to stay away from giving away too much, but I’ll still keep everyone up to date and posted on what happens in the second half. That’s all for now, and thanks for reading!

Works Cited:

Driftwood. Digital image. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 July 2017.

Macfarlane, Robert. The Wild Places. London: Granta , 2010. Print.

Ocean Phosphorescence. Digital image. Pinterest. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 July 2017.

The qualities of wood for your wood ring. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 July 2017.

The Wild Places. Digital image. Amazon India. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 July 2017.

Advertisements Share this: