Australian Women Writers Gen 1 Week 15-21 Jan. 2018

The author of this guest post is Michelle Scott Tucker (MST of Adventures in Biography) whose Elizabeth Macarthur: A Life at the Edge of the World is due out in April. Michelle’s essay on the very first of our first generation of women writers provides the perfect lead-in to AWW Gen 1 Week. Thank you Michelle.

Australia’s First Women Writers – a piecemeal and imperfect overview enlivened by a giveaway at the end.

European women and men, as soon as they arrived in New South Wales, began writing letters to those they had left behind. So perhaps Australia’s first women writers could more accurately be labelled correspondents.

As Aboriginal people had been doing orally and pictorially for maybe 60,000 years, the European colonists used letters, diaries, drawings and paintings to share their stories, news, and hopes. Many of these sources are well-known and well-used, particularly the earliest ones, and historian Inga Clendinnen, in Dancing with Strangers, felt that all the archival material covering the early encounters of the British and Aboriginal peoples ‘takes up not more than one solid shelf.’

But, until relatively recently, Australian history tended to exclude the writings of women – it was too personal, too domestic, too unimportant. This was, of course, complete rubbish. From the female correspondents, we gain a fascinating perspective on the colonial experiment, a perspective that often belies the formal reports and documents recorded as ‘History’.

But I won’t pretend to provide any sort of comprehensive overview here – instead I’d simply like to share with you some of my favourite women correspondents, and the books in which their letters and diaries can be found. Clendinnen’s hope was that ‘readers will be stimulated to read some of that material themselves’. That’s my hope too and, like Clendinnen, ‘I promise they will be rewarded’.

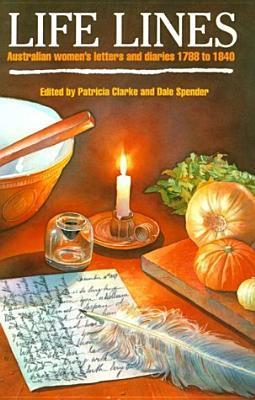

A terrific place for the general reader to begin is with Patricia Clarke and Dale Spender, in their excellent book Life Lines: Australian women’s letters and diaries 1788-1840. Clarke and Spender provide intelligent commentary, and the many excerpts they include are comprehensive and fascinating. Even the categories Clarke and Spender use to group women writers are illuminating and include: Forced Labour, Farm Managers, The Work of the Lord, Shipboard Travail, Charitable Works, Vice-regal Duties, Working Wives and Mothers, Shopkeepers and Needlewomen.

The following information, about convict women writers, is drawn from Clarke and Spender.

Convict Women

Few letters from convict women survive, and no diaries. Many of the convict women (and men) were illiterate, of course, but certainly not all, and their letters were, in many cases, crafted with creativity and skill.

The first letter we have from a convict woman (anonymous) was written on 14 November 1788.

I take the first opportunity that has been given us to acquaint you with our disconsolate situation in this solitary waste of the creation. Our passage, you may have heard by the first ships, was tolerably favourable; but the inconveniences since suffered for want of shelter, bedding & c, are not to be imagined by any stranger. However we now have two streets, if four rows of the most miserable huts you can possibly conceive of deserve that name. Windows they have none, as from the Governor’s house & c., now nearly finished, no glass could be spared; so that lattices of twigs are made by our people to supply their places.

She goes on to describe attacks on the colonists by Aboriginals, the convict women’s lack of clothes, and the pitiable situation of women who, on the voyage out, fell pregnant to sailors now long gone. Meals were ‘insipid’ for want of sugar and salt. ‘In short, every one is so taken up with their own misfortunes that they have no pity to bestow on others.’

A second letter survives from a convict woman who arrived in 1790, aboard the Lady Juliana (for an account of the voyage, try The Floating Brothel). Of the one thousand or so convicts sent out in the second fleet, more than a quarter did not survive the journey. The anonymous convict woman wrote that those who died after their ships entered Port Jackson were flung overboard, and their unweighted corpses washed up on the shore. Nearly half the convicts were landed sick. Upon reaching dry land some creeped upon their hands and knees, and some were carried upon the backs of others. All were filthy and emaciated. Governor Phillip was furious with the captains, wrote the convict woman: ‘I heard him say it was murdering them.’ Phillip’s dispatches back to England were, however, far more circumspect.

Farm Women

Elizabeth Macarthur, then the wife of an officer of the garrison, also arrived with the Second Fleet in 1790, although not aboard the Lady Juliana. She and her family would go on to establish the Australian wool industry.

As a correspondent and diarist, she was very much a typical colonial woman writer, but we know more about her, and have more of her letters, because of the wealth of material made available to us by her descendants. The Macarthur Papers, housed in Sydney’s Mitchell Library, amount to some 450 volumes, as well as boxes, maps and plans. In basic terms, we simply know more about Elizabeth, and her family, than we do about her female peers.

It is crucial to understand, though, that with the exception of Elizabeth’s journal recording her 1790 voyage to New South Wales, the letters that are available to us now are in fact excerpts and transcriptions – painstakingly copied out by Elizabeth’s grown-up children. We cannot know the extent to which they edited their mother’s original words, or censored them. Unfortunately, this is true of many colonial letters and diaries.

A selection of John and Elizabeth Macarthur’s letters were published as early as 1914 in a collection edited by Elizabeth’s great-granddaughter Sibella, but a comparison of the letters in the book with even a few of the ‘originals’ reveals changes in word order and whole sentences missing. And is it significant that, with a single benign exception, none of Elizabeth’s letters to her husband survived? Did John read and immediately destroy them? Or was it their children who did that, all too keen to remove any evidence that their mother might not have been entirely satisfied with her lot.

Elizabeth’s descendants did not, however, manage to completely erase her ability to pen a telling phrase. She described the nefarious captain of her ship as a ‘sea monster’ and in a much later letter drolly apologised to her adult son for not writing sooner. Instead of hiding away at the writing desk ‘I kept myself disengaged to talk, which occasionally you know Edward I am very fond of’. In another letter Elizabeth describes a Macarthur family visit (which she did not attend) to see her husband’s nephew Hannibal Macarthur at his Parramatta property, the Vineyard. In time the Vineyard would boast a fine, two story Georgian house but in the late 1820s Hannibal and his wife Maria were still living in the original small cottage. When Elizabeth’s family visited, two of Hannibal’s brothers were expected any day from England; Maria Macarthur a few weeks earlier had given birth to her eighth child; and Maria’s sister-in-law, also staying at the Vineyard with her family, had just given birth to her seventh son. ‘You may imagine,’ wrote Elizabeth, ‘the Vineyard cottage was well peopled. They must be as thick as hops.’

It is striking that Elizabeth’s existing letters are, with few exceptions, uniformly positive and cheery. This is possibly due to family censorship but may equally have been a result of self-censorship and a reflection of the circumscribed nature of women’s letters. Like other correspondents of the period, Elizabeth expected her letters to be widely read, at least within the family, and so did not necessarily consider them private documents. Maria’s sister-in-law (the one with the seventh son) summed up the problem in a letter to her husband. ‘I could make you laugh if I were near you but do not like to put my funny stories on paper.’

Clarke and Spender include excerpts of Elizabeth’s letters but the best hardcopy sources of at least some of Elizabeth’s transcribed letters are:

- Hughes, J (ed), The Journal and Letters of Elizabeth Macarthur 1789-1798, Historic Houses Trust NSW, Sydney, 1984.

- Macarthur Onslow, S, The Macarthurs of Camden, Rigby, Adelaide, 1973.

Both are out of print though, and the former is particularly difficult to find. The State Library of NSW is in the process of digitising many of Elizabeth’s letters but, to my knowledge, few if any are as yet available online.

Maria’s sister-in-law Harriet endeared herself to me with her published letters but again the book, called The Admiral’s Wife: Mrs Phillip Parker King, is out of print and hard to find. Goldfields Library Service (in Victoria) have a copy, if you’re keen.

Diarists

In the 1840s Anne Drysdale and Caroline Newcomb successfully farmed in Victoria. Drysdale’s diaries survive, and extensive excerpts were published by the State Library of Victoria. It’s a fantastic little book. The blurb states, in part:

In 1839 Miss Anne Drysdale sailed from Scotland to Port Phillip. She was 47 years old, had a small inheritance, and was determined to be a sheep farmer. Soon after arriving in Melbourne, she took up land near Geelong and formed a partnership with another enterprising woman, Caroline Newcomb. They established a successful pastoral business, and for thirteen years lived and worked together on their properties.

Interestingly though, the book doesn’t include the diary excerpt that has Miss Drysdale describing how she joined a shooting party with the express aim of killing Aboriginal people. A brief footnote in Bruce Pascoe’s Convincing Ground brought that harsh point home to me. Another example of the need to be aware of what is left out.

Another fascinating diarist is Mary Braidwood Mowle (1827-1857), who lived in what is now the Canberra region, before moving to Eden, on the NSW South Coast. She provides many personal insights, including her description of childbirth as ‘the dreaded ordeal’. Mowle’s diaries have her galloping over the Limestone Plains in the heat of January with her hair flying; terrified in a gale when sailing with her children to Tasmania; absorbed in polite conversation in the drawing room of a Braidwood property. Again, Patricia Clarke edited this one.

Connections

Clarke and Spender argue, and I agree, that the letters and diaries of Australia’s first women writers ‘provide clear and creative examples of the connections between women’s letter writing and the growth and development of fiction.’ These women told exciting stories of their lives in the colonies, using the features of suspense, structure, and humour. They wrote to maintain family ties, and – some of them – as a creative outlet. Their letters are variously engaging, intelligent, funny, and heartbreaking. Some are deeply conventional, others are just as deeply subversive.

Modern-day writers seeking to understand the colonial ‘voice’; historians seeking insights; readers wanting to know more about colonial Australia – women’s letters and diaries provide all that and more. But really, they are well worth reading simply for their own sake. Why don’t you give them a try?

Giveaway!

In the course of writing this post, I discovered that I have two copies of Clarke and Spender’s Life Lines. Both were purchased second-hand, and are in good (but not pristine) condition. I don’t need two copies, so I’m happy to give one away. If you live in Australia and you’d like me to send you a copy, leave a comment saying so by 31 January 2018 and we’ll choose a winner at random.

Books mentioned above

Clarke, P, A Colonial Woman: The Life and Times of Mary Braidwood Mowle, Allen & Unwin, Sydney,1991.

Clarke, P, and Spender, D, Life Lines: Australian women’s letters and diaries 1788-1840, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1992.

Clendinnen, I, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2005.

Hughes, J (ed), The Journal and Letters of Elizabeth Macarthur 1789-1798, Historic Houses Trust NSW, Sydney, 1984.

Macarthur Onslow, S, The Macarthurs of Camden, Rigby, Adelaide, 1973.

Pascoe, B, Convincing Ground: Learning to fall in love with your country, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2007.

Rees, S, The Floating Brothel, Hodder, Sydney, 2001.

Roberts, B (ed), Miss D & Miss N: an extraordinary partnership, Australian Scholarly Publishing with the State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, 2009.

Walsh, D (ed), The Admiral’s Wife: Mrs Phillip Parker King, The Hawthorne Press, Melbourne, 1967.

Advertisements Share this: