A few weeks ago, I spent a day helping in a history booth at a street fair in Hannibal, Missouri. Our booth was located just half a block down the street from the boyhood home of Samuel Clemens—American author Mark Twain.

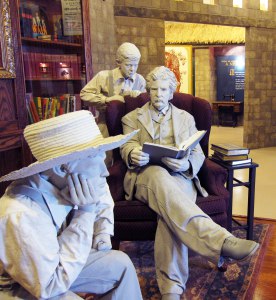

A sculpture in the Mark Twain museum in Hannibal, Missouri, depicts the author reading as Tom Sawyer looks over his shoulder and Huck Finn feigns disinterest.

Twain has always been one of my favorite authors. Even though he delighted in being an iconoclast and critic of behavior, I have always believed he was basically honest and fair and believed in the equality of human beings—notwithstanding some of his biting satire. (He did not have much good to say about members of my faith, but I am convinced it was only because he never came to know the “Mormons” well enough. Some of Twain’s expressed beliefs are quite congenial with Latter-day Saint doctrine.)

It distresses me to see that his books are banned or criticized by some these days as being “racist” because in his writing he used what we now carefully call “the N word.” Criticisms come despite the fact that in Huckleberry Finn, Twain exposes the evil and folly of slavery, along with the hypocrisy of many Christians in response to this and other faults in the society of their time.

Now, some also oppose the reading of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, again accusing the book of fostering racism. Like Huckleberry Finn in its day, To Kill a Mockingbird was a powerful voice against the evil and stupidity of racism. I first read the book when I was a senior in high school, just when the civil rights movement was gathering its power. For my generation, To Kill a Mockingbird was a clear call to white people that it was long past time to let go of ignorance and prejudice toward African-Americans. The book challenged us both emotionally and logically to see others for who they are as individuals and not as part of a group or category. Perhaps not everyone was swayed or influenced by To Kill a Mockingbird, but many of us saw it as a landmark in the intellectual landscape of our lives.

As people of the early 21st century, we quickly wander into a maze of error, emotionally and logically, when we judge the actions of others in the past by the sensibilities of our current decade or of our social group. Let me offer examples that are both personal and sensitive.

My mother’s parents were wonderful people, both great guides to me. I heard both of them at times use the N word, because that is what they grew up knowing. My grandmother had been born on an old estate in Louisiana that was a slave plantation just 30 years before her birth. My grandfather, having grown up in West Texas and down along the Rio Grande, often spoke of “Mexicans” when he meant Mexican-Americans. But neither of my grandparents ever spoke in demeaning ways of another person. They were about as far from racists as anyone I have ever known.

When I was a small boy, both my mother and grandmother were incapacitated for a time, recovering from a car accident. My grandfather hired an African-American woman named Rosa (yes, Rosa) to help with the housework. One day I complained about Rosa because she had tattled on me to my mother when I did something I shouldn’t have. This led to a discussion with Grandma in which she made it clear in no uncertain terms that I was to treat Rosa like the daughter of God that she was. Rosa, Grandma taught me, had a hard life trying to support and care for her aged mother, and I was never to do anything to make her life harder. Rosa was a person to whom I owed respect, not because she was part of a particular ethnic group, but because she was another human being. I can’t recall that the subject of Rosa’s skin color ever came up.

My grandfather the plumber often hired helpers when I was a boy. I remember a couple of down-and-out Anglo-Americans he hired to give them a new start. I remember a Mexican-American he liked to employ because the man was a good worker. I cannot remember that the subject of ethnicity ever came up in connection with these men’s work. Grandpa wanted workers. He dealt with his employees as people, not as representatives of an ethnic group.

Even when my grandparents were taken advantage of by people from other ethnic groups, I never heard them condemn the group. I learned from them that every individual should be viewed as a child of God worthy of respect and kind treatment, and if some did not live up to that treatment, it was because of personal weakness, not ethnic background.

No doubt there are some who may judge me as racist or say I am likely to be prejudiced based on my color and ethnic background, my faith, my education, the region where I live, etc. People who want to find a reason to criticize will find one. The list of reasons we can find to judge other people harshly is endless—if we are looking for reasons to support our own biases.

I have a very visible birth defect. Because of it, I have been stared at, categorized, shut out of some opportunities in this life, and treated at times as though my mind is probably also defective. I am sure no one else has faced exactly the same circumstances I have faced. Others could never fully understand my situation. And if we all apply this same line of reasoning to our own lives, humanity will be subdivided into nothing more than billions of small, socially and intellectually isolated islands.

But together we are more than that, and we need each other. To me, this is one of the important lessons of works like Huckleberry Finn and To Kill a Mockingbird. Of course we are all diverse, but differences, like skin color, are not nearly so important as the divine heritage that we share through the eternal spirits that inhabit our bodies. We are much more alike than we understand—or sometimes care to admit. Anyone caught up in bigotry sees everyone else as a lesser being in one way or another.

Years ago I spent some time traveling with a performing group whose members were from many different ethnic backgrounds. One of the group’s musical numbers was introduced with the thought that none of us is truly black or white or red or yellow. We are all the multi-hued browns of Mother Earth, and our basic needs and wants are the same. The measure of our worth is always at the individual level, not the group. There is no moral evidence to suggest that God will judge us as members of our group, but He will judge us as the individuals we have become.

Our present-day society seems so divided according to special interests—ethnicity, religion, social status, education, income group, age, etc.—that we are losing the ability to see each other as individuals. No sooner do we meet someone than we begin to search in our minds for the proper way to categorize or label that person. We cannot see the trees for the forest.

The solution to our problems on this small planet in a vast universe is to learn to see each other as brothers and sisters in the family of God.

Impossibly optimistic?

No—realistic.

It is the only way I can see for all of us to survive.

Share this:

- More