★★★★

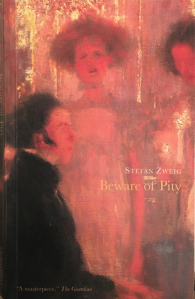

When I was packing for my Vienna trip last week, one very important question was on my mind. What should I take to read? I always enjoy reading appropriate fiction on my travels, but it turned out that my collection of Austrian stories was rather limited. By stretching the rules, I ended up choosing this: the only full-length novel by Stefan Zweig, the wonderful essayist, biographer and short-story writer who was born in Vienna. Beware of Pity was first published in 1939 and looks back to the eve of another war, in 1914 on the borders of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It’s a simple story, about an act of kindness that goes horribly wrong – and Zweig’s percipient understanding of human nature means that it resonates strongly even today.

Our protagonist is Anton Hofmiller, a young lieutenant in the Austro-Hungarian cavalry who finds himself stationed in a quiet garrison town. Living on a tight salary, Hofmiller is bored by a tedious round of mess dinners, trips to the cafe and unsatisfying flirtations with the local girls. Unsurprisingly, he leaps at the chance to be introduced to a local worthy, Herr von Kekesfalva, who is renowned for feting young officers and providing splendid dinners. A party at the nobleman’s estate gives Hofmiller a glimpse of the kind of elegant life he pines for. There’s excellent wine, good company and, most appealing of all, two young women: Kekesfalva’s radiant niece Ilona, and his frail daughter Edith.

And it’s here that Hofmiller takes the fatal step that will lead him into trouble. At the party, he attempts to show off his good manners by asking Edith von Kekesfalva to dance. But disaster ensues. For the young lady is lame – scarcely able to walk – and Hofmiller’s well-meaning invitation reduces her to tears. Mortified, the young officer makes his exit; after wondering how to apologise, he sends her flowers; she responds inviting him to tea; and, before he knows it, he has been assimilated into the family’s inner circle. It’s a glimpse of a world that Hofmiller has never known: fine dinners, pleasant tea parties and affectionate teasing with the two girls. For him, it’s a charming way to spend his afternoons and he’s thrilled to see how his company invigorates the household, making the two girls happy and cheering up old Kekesfalva, who is delighted to see his daughter looking forward to something for a change.

Hofmiller’s visits begin through embarrassment, but they continue through pity for Edith, whose housebound life he hopes to brighten up. And his motives aren’t entirely altruistic, for his actions give him a warming sense of his own significance: ‘It is never until one realizes that one means something to others than one feels there is any point or purpose in one’s own existence.’ And so the visits continue, Hofmiller learning to tackle Edith’s frustration and shifting moods, and falling into the comfortable notion of having an adoptive family. But, presently, it becomes clear that he has desperately misread the situation. For, where he intends friendship, Edith has inferred something else. And, where Hofmiller looks on the Kekesfalvas as a surrogate family, Edith and her father have high hopes that they will soon become family in a more official sense.

The book is a slow-burner, told from Hofmiller’s perspective and allowing you to see – even while he remains oblivious – how his actions raise Edith’s hopes. The whole thing feels so plausible, so painfully real, because Hofmiller is far from being a noble hero – yet nor is he a villain. He’s simply a well-meaning, self-centred, ambitious young man, eager for the respect of his fellow officers and keen to taste a bit of the high life. Edith is equally complex: she isn’t the wilting innocent invalid of Victorian fiction but a passionate, frustrated and susceptible young woman, who has lost her legs but not the ability to feel desire or indignation or anger at her predicament. She sometimes comes across as unstable, when seen through Hofmiller’s eyes, but I can’t help feeling that Zweig has captured the fury that we would all feel in a similar position. It’s because these two characters are so convincing that the story hits so deeply.

And Zweig is also excellent at suggesting the various social bonds, which each exert their own obligations and demands. Hofmiller is a cavalry officer which means he must abide by certain rules even in private life, so as not to dishonour his regiment; he is a young man of modest fortune, eager to stay on the right side of his superiors; he hopes to win the affection of Herr von Kekesfalva; and his vanity is flattered by the attention of the girls. When his different obligations begin pulling him in different directions, Hofmiller has to decide whether to keep Edith happy in the short run, or to break her heart in the long run – a choice that will stretch his courage to the utmost.

Beautiful, thoughtful and heartbreaking in equal measure, this book deals with timeless questions about duty and compassion – while also giving an elegiac picture of life on the brink of the First World War. I didn’t always feel that Zweig is quite as successful a novelist as he is an essayist, but he understands people, their strengths and their flaws, in a way that is quite remarkable. Certainly recommended to those who fancy something lethargic and poignant, but be warned: this certainly isn’t an upbeat story. A quick note on the translation: my 2006 Pushkin edition has the 1982 translation by Phyllis and Trevor Blewitt, but the most recent (post-2011) editions from the same publisher use a new translation by Anthea Bell. I’ve scan-read her introduction and can’t see too much difference, but it might be interesting to compare the two translations properly at some point. It seems to me that more recent translations are often livelier and even more engaging, so perhaps in its new form the novel is even more of a treat.

So I’ll leave you with a question. Which books have you read about Vienna and, next time I go there, what should I take with me for reading material?

Buy the book

Share this: