K. W. Jeter was one of the young, aspiring writers, along with Tim Powers and James Blaylock, who hung around Philip K. Dick in his last years.

Amongst other things Dick would do — and Powers definitely says Dick was not, per popular legend, “crazy” — is spin late night conspiracy theories out which would keep the young men in a state of paranoia for a couple of days until Dick would reveal the joke.

Jeter is also the man who jocularly invented the term “steampunk” for the sort of work he, Powers, and Blaylock did early in their careers.

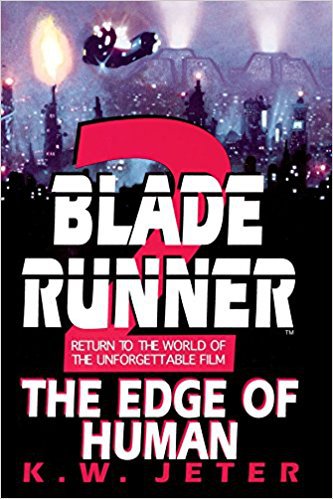

Raw Feed (1999): Blade Runner 2: The Edge of Human, K. W. Jeter, 1995.

This is a peculiar book, unique, as far as I know, in its intentions and starting premises.

There are several media tie-in books that use characters from tv shows and movies. There are also some books that are sequels to other authors’ works. This novel, though, combines both. To further complicate matters, there are two versions of the film Blade Runner. [My box set of Blade Runner films actually has five versions.] Jeter seems to use the original version of the film as the beginning point of his plot.

Jeter drags out all the usual Philip K. Dick elements: conspiracies (I think he outdoes Dick in this regard – more on the par of A. E. van Vogt who inspired Dick) and the tenuous nature of reality and some specific references to the universe created in Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, specifically Deckard’s increasing disgust with killing androids and the nature of humanity and the constantly blurring lines between human and android and the sometimes questionable desire to make a distinction.

The plot is satisfyingly engaging though not without problems.

Jeter takes a seeming discrepancy in the remarks of Bryant in the film about the number of Nexus-G androids needing retirement to build a paranoid plot about Sarah Tyrell’s (the Tyrell niece mentioned in the film as the model for Rachael but never seen) covert attempt to destroy the Tyrell Corporation, a symbol of her hated uncle Eldon who incestuously abused her. Here she is a survivor of the Salandar 3 expedition mentioned in the novel. Jeter never does give a satisfactory answer as to why the expedition’s records were heavily classified.

Her substitution of her herself for Rachael (whose life span is extended by long bouts of suspended animation as she hides with Deckard in the wilderness) – and Deckard’s knowing acceptance of that – was interesting and plausible for a couple of reasons.

First, it extends the theme of Dick’s novel in that even loved based on false assumptions and pretensions can be satisfying.

Second, it is a continuation of a, perhaps, unintended theme of almost animalistic, simple-minded tropism in love and affection. Deckard is willing to accept Sarah as a substitute for Rachael because she looks identical to his dying love (and, in the Dick novel, his initial attraction to Rachael is almost entirely sexual). However, Sarah does share some memories with Rachael.

This theme is also present in J. R. Sebastian’s, who is still roaming around with his toys though now missing three limbs he self-amputated to stave off his Methuselah Syndrome, love for the weirdly preserved, animalistic Pris. She, in fact, may have been a human psychotically identifying with replicants and mistakenly retired by Deckard and revived by Sebastian.

Jeter, as in parts of his novel Noir, can’t seem to abandon his predilection for horrific scenes with no rational. He doesn’t explain how Pris survives, for so long, from a shot to the head.

For that matter, both Jeter and Dick exhibit some confusion about their androids. Parts of their bodies are described in machine terms yet we’re told only bone marrow tests can conclusively establish human or android identity. Perhaps one explanation is that medical implants can give any human replicant-like parts.

The convoluted plot, which brings out the briefly seen Holden of both book and film and has a set-piece where the UN advertising blimp is destroyed, has many questions of identity. Are Deckard and/or Holden a replicant? Are all blade runners replicants? One premise turns out, reasonably and surprisingly, to be a misstatement of Bryant’s alcoholic brain thus rendering moot his replicant count in the film.

The main premise of Sarah setting Deckard and Holden and Roy Baty (the human model for the replicants, nicely rendered by Jeter) against each other to discredit the Tyrell Corporation and its androids was fairly plausible. However, couldn’t she have just destroyed the corporation herself or made damaging revelations? And, from the mess of the novel’s end, how exactly is the UN to infer that a sixth replicant is loose and/or blade runners fail.

Baty gives an explanation of the origin of the term “blade runner” and how they are all replicants, but he may be unreliable. We don’t know.

Jeter tries to rationalize a lot of things from the film like its costuming.

The theme of also not caring about the difference between mechanical simulacra and life is nicely done with the scenes with Isidore who literally can’t tell the difference between his real and synthetic animals at a Pet Hospital. He also serves as something of a moral voice for the novel when he condemns Deckard.

Another problem is how Sarah, who wants to start life anew with Deckard, can be sure he’ll survive his struggles with Baty and Holden.

Still, despite some shaky plotting and rationalizations, it was interesting enough to see this world and these characters again in a plot with a healthy dose of unremediated paranoia.

More reviews of fantastic fiction are indexed by title and author/editor.

Advertisements Share this: