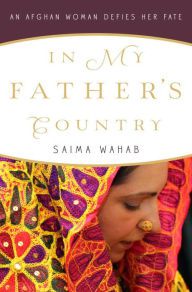

I have had Saima Wahab’s memoir In My Father’s Country: An Afghan Woman Defies Her Fate on my To Read list since I saw her interview on the Daily Show several years ago. Documenting her childhood in Afghanistan and then Pakistan as a refugee before moving to the United States to further her education, become a US citizen, and eventually travel back to Afghanistan to assist US troops during the war–and given the current political climate in the US—it seemed like the perfect time to finally make myself read this book.

I have had Saima Wahab’s memoir In My Father’s Country: An Afghan Woman Defies Her Fate on my To Read list since I saw her interview on the Daily Show several years ago. Documenting her childhood in Afghanistan and then Pakistan as a refugee before moving to the United States to further her education, become a US citizen, and eventually travel back to Afghanistan to assist US troops during the war–and given the current political climate in the US—it seemed like the perfect time to finally make myself read this book.

First published in 2012, Wahab’s memoir begins with her earliest memories of life in Afghanistan as the Soviets invaded the country and her outspoken and rather liberal father was among the first taken into custody. She never saw him again and her family fled first to her father’s people in their small village and then across the border to Pakistan where they were safer. Wahab notes that even from a small age, she rejected elements of her native culture, especially with regards to how the women were controlled and restricted by the men of their families. Sent to her uncles in the US as a teenager along with her siblings and cousins, she embraced many of the freedoms of American culture even as it caused her to struggle with holding onto and preserving her sense of her culture as a Pashtun woman. Once she begins her exploration of her time working as a civilian alongside US forces in Afghanistan–first as an interpreter and then as a research manager on an HTT (Human Terrain Team) where she helped research and map the cultural differences between the villages in Afghanistan—her narrative focuses on her struggle to reconcile the two sides of her identity, Pashtun woman and American woman. Speaking the language and understanding the culture of the locals, she worked to educate and guide both the US soldiers and the local Afghan peoples as the nations aimed to work together to rebuild her father’s country.

Having taken classes in college about the history of the area that included a breakdown of some of the ethnic groups, the tensions between them, and the differences between their cultures, I came into the book with some basic knowledge but Wahab doesn’t presume her readers will have that and does a fantastic job of giving that overview as she goes, focusing most especially on her Pashtun heritage and culture. The tension she felt/feels between her native and adoptive cultures is obvious in her presentation of both and inspires empathy for all sides affected by the war; she doesn’t seek to cast blame and only occasionally references anything to do with the war’s origins. Everything is about fostering understanding, explaining each side to the other so that they could work together with respect for one another, and so she could find a way to be both American and Pashtun herself without feeling like she was choosing one over the other.

Bringing her focus down to the personal level–and making it so very personal because it is her life, her family, her friends, holding little back—it becomes about the people involved rather than the larger war and tactics and such. You don’t need to have an intimate knowledge of the war on terror as it unfolded in Afghanistan (and later Iraq) in order to follow Wahab’s journey. She provides a few markers and references as the Bush Administration’s policy and approach shifted; there is little noting if/how Obama’s election and the change of administration affected anything, but then the focus of her narrative ends in 2009. This narrower personal focus is part of what makes Wahab’s story so compelling; it never aims to be a large, all encompassing analysis but rather demonstrates the differences one person can make by starting small.

Advertisements Share this: