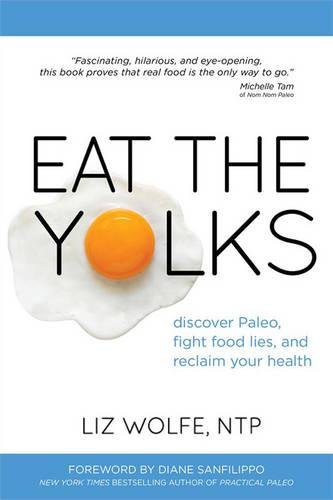

3 stars. I was intrigued by Outside Magazine’s glowing review of Jim Shepard’s new short story collection, The World to Come The expectation of greatness was amplified by the book jacket description:

3 stars. I was intrigued by Outside Magazine’s glowing review of Jim Shepard’s new short story collection, The World to Come The expectation of greatness was amplified by the book jacket description:

“These ten stories burst with his wicked sense of humor and incomparable understanding of what it means, and has always meant, to be human. The World to Come is the work of a true virtuoso.”

I’d say that sets the bar pretty high…

The author indeed has a gift for giving his characters distinctive voices. He’s captured period diction almost perfectly, from the dry “stiff upper lip” of British explorers to the pioneer diary of an upstate New York woman to the elaborate and stylized prose of the dying days of the French aristocracy. The author’s obvious talents are on display in a second-person story of the destruction of Santorini. Shepard’s settings are clearly exquisitely researched as well, rich with details that give authenticity to a WWII submarine and a crude oil train conductor’s experiences.

For all the writing skill, The World to Come was largely “meh” for me largely because I never made an emotional connection with the characters. Two of the stories are told in a journal format, which relate events instead of developing characters. Stories such as “The Ocean of Air” overwhelmed with detail to the exclusion of personality. “Intimacy” and “Safety Tips for Living Alone” presented a wide cast of characters but spent so little time with any one that they seemed largely interchangeable. “Wall-to-Wall Counseling”, “Forcing Joy on Young People”, “Telemachus”, and “Positive Train Control” all featured detached characters who didn’t relate to those around them, and thus were never able to reach me.

My chief critique of Shepard’s writing is that there is very little dialog. This inhibits character relationships from developing. Most characters feel like the anti-Donne: every one is an island, and when the bell tolls for them, it doesn’t toll for me.

Many of the stories ended with the implied death of their subjects. This prevented me from experiencing closure and catharsis necessary to appreciate the theme of the story. The first-person narration of many of the stories limits this by nature; in others, they end with no conclusion.

I felt that my enjoyment of a particular story was largely tied in with my interest in its subject matter, which left the collection feeling uneven. The three-page “Cretan Love Song” was my favorite because it captures the raw emotions of the destruction of Santorini so poignantly. “Safety Tips for Living Alone” is an intriguing account of the Texas Tower 4 disaster; a foreboding sense of doom kept me turning the pages. “HMS Terror” is another high point. Its scholarly journal entries added to the classical tragedy feel of the lost Franklin expedition. Shepard’s masterful foreshadowing in “Positive Train Control” adds power to his scathing indictment of the lack of safety focus in the crude oil trains that feed our energy dependency. “Telemachus” reads like pulp WWII fiction with its fatalistic narrator and high-stakes deeds.

On the down side, “Wall-to-Wall Counseling” portrayal of a woman facing family and work crises ended without resolution, character development, or theme. Similarly, “Forcing Joy on Young People” meandered aimlessly here and there throughout its principal character’s life, and he was so flawed that the only conclusion I could reach is that he deserved what he got.

I do not regret reading The World to Come; nor did I feel any regret when I turned its final page.

Advertisements Like this:Like Loading... Related