This review includes a fairly detailed summary of the plot. I leave the plot twist out though.

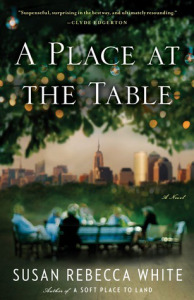

I’ve had an ARC of Susan Rebecca White’s book for years now. Sorry, Susan. But I’m glad that I waited this long to read it, because maybe I wouldn’t have appreciated it as much before I’d matured some more.

This is a heartbreaking story of pain and trauma, of otherness, of love and marriage and ultimately of survival, finding oneself, forgiveness, family, and accepting one’s roots and backstory.

This story follows three primary characters, whose lives all intersect over a cookbook and a shared love of food and a bright and cozy kitchen. It begins in 1929 in Emancipation Township, a black community in the rural, Jim Crow South. There we’re introduced to young siblings Alice and James Stone, close enough to believe that they are able to read one another’s thoughts. After refusing to play the meek black man, James is forced to flee North Carolina.

Leaving the Stones, we join Bobby Banks, a pastor’s son, white, probably upper-middle class, in 1970 Decatur, Georgia. His Meemaw lives in a neighborhood that is now mostly African American. He tries to befriend one of the neighborhood girls, but his brother’s racist language thwarts that. Later in 1977, he finds himself friends with a displaced Yankee, his equal on the track team. The two of them find themselves more than friends when alcohol, a late night, and a sleepover coincide, and Bobby begins a life in exile from his family, first with his Meemaw and later, in 1981, in New York City, where we stay with him through 1991. Bobby during his early years in New York finds himself working at the restaurant, a once-renowned haunt of writers and bohemians, where Alice Stone was once the well-known and –loved chef. He returns the restaurant to its gentrified-Southern roots and gains fame for himself. His time in New York coincides with the AIDS epidemic of the ‘80s, and he loses his lover and partner to the disease.

Alice’s editor and friend has a niece, Amelia, living in upper-middle class Connecticut. She marries a Southerner from Georgia, who as they begin their life as empty-nesters in 1990, turns emotionally abusive towards her. She struggles with her desire to make her marriage successful and the fear for her own safety.

Individually, each character’s story of hardship and survival is fascinating.

If I was not necessarily eager to return to this book between minutes I was able to read, neither did I want to stay away, with which as much heartache as was in the book and knowing that I tend to avoid reading about characters in deep pain, I think must mean that these characters were well-developed and compelling.

For all that Alice is the glue that holds these stories together (it’s Alice’s restaurant that takes in Bobby, and Alice’s editor’s niece), it’s Bobby with whom we spend the most time, and whose story is explored most fully. As the true tale unwinds, Bobby, though, seems the outside observer, and the story seems more fully Alice’s and Amelia’s and James’. That was a little jarring, but Alice, Amelia, and James’ story makes up in emotional wallop what it lacks in page count.

What all these characters share—apart from a love of good food and cooking—is an exile from family, a crumbling of the idyllic family, and a longing for the return to home (Alice’s cookbook is Homegrown). Alice’s family is broken when James is forced to flee, and James’ worldview is shattered when he realizes himself to be part-white before being forced to flee his home. Bobby is kicked out of his family home after he is discovered kissing a boy. On his grandmother’s advice, he like James before him, leaves the hostile South altogether for the rumored, liberal paradise of New York City. Amelia has never spent time in New York—her family never visited, though they were nearby—but when her own marriage falls apart and with her children out of the house, she finds herself seeking comfort from her aunt, who lives there. Alice and Bobby both cling to their Southern roots through the food that they eat and prepare for others, even as they make new lives for themselves in New York. Amelia discovers her own Southern roots.

None of the characters return to the South but each of them is awarded some measure of reconciliation with their families. So it seems that family is the root to which White argues that one should return and with which one must reconcile to be fully known to oneself.

***1/2

White, Susan Rebecca. A Place at the Table. New York: Touchstone-Simon & Schuster, 2013.

This review is not endorsed by Susan Rebecca White, Touchstone, or Simon & Schuster, Inc. It is an independent, honest review of an ARC by a reader.

In the interest of full disclosure, Miss White is an alumna of the graduate program at my alma mater.

Advertisements Share this: