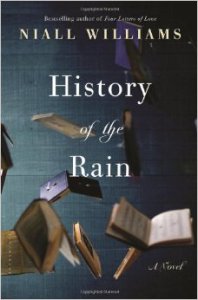

First Published: 2014

Number of Pages: 358

Publisher: Bloomsbury

Genre: Fiction

Sub-Genres: Contemporary fiction

Note: this post contains an affiliate links.

A while back, a friend of mine, after finding out that I love Irish literature, recommended this book to me. I’m terribly glad that he did. The one-sentence review he gave of it on his blog sums it up pretty nicely: “This is a thing of beauty.” Just the same, I’d like to add a few words to that.

A while back, a friend of mine, after finding out that I love Irish literature, recommended this book to me. I’m terribly glad that he did. The one-sentence review he gave of it on his blog sums it up pretty nicely: “This is a thing of beauty.” Just the same, I’d like to add a few words to that.

On its surface, History of the Rain is the story of the Swain family as told by one of its last surviving members, nineteen-year-old Ruth Swain. Having been confined to bed by a mysterious illness, Ruth begins writing her family’s history in order to “find” her late father, a poet named Virgil Swain. Really, though, this book is about a lot of things.

It’s about perfection and the impossibility of attaining it. For instance, one recurring theme in the Swains’ history involves sons who fail to live up to their own and their fathers’ expectations for them. Beginning with Ruth’s great-grandfather, a zealous English minister determined to make a difference in the world, each generation of Swain men tries to live up to the impossible goals he sets for himself, fails, and then tries instead to find his ultimate fulfillment in making his son all he hoped he would be himself. The tradition of remaking the son in the father’s image, fortunately, stops with Virgil Swain. Nevertheless, Virgil is still haunted till his dying day by a desire to find or create perfection and sublimity in everything he meets. “My father bore a burden of impossible ambition,” Ruth tells us on the first page. “He wanted all things to be better than they were, beginning with himself and ending with this world.” Again and again, the book returns to the idea of longing for something out of this world, of missing something that was never ours in the first place. In a way, it reminds me of C. S. Lewis’s memoir Surprised by Joy, in which he describes his experience of an insatiable longing for something that he had never yet found, calling this longing either “Joy” or sehnsucht. But where Surprised by Joy was concerned mostly with how Lewis found a consolation for that longing through his faith, History of the Rain is more concerned with the longing itself: how and when it appears and the futility of trying to satisfy it with earthly things. The book gives no answers but asks a lot of questions, enough to put you into that mindset of longing and wishing and hoping as well.

This is also a book about books. For both Ruth—trapped in her room with nowhere else to go—and her father—dogged by that sense of sehnsucht I mentioned a minute ago—books are an escape. They remind them that there’s a bigger, better, and more beautiful world out there than anything they could imagine. Books also become the link between them after Virgil dies. He owned 3,985 books at the time of his death and Ruth says she’s going to read them all. That’s another way in which she intends to “find” him. So between the narrator’s passion for reading and her frequent references to great books and authors, you might say that History of the Rain is a kind of love letter to literature and to the people who create it.

Speaking of writers, the writing in this book, for me, was one of its real high points. Williams’s style is intensely lyrical and imaginative throughout, with just a touch of stream of consciousness. The idea is that Ruth is a writer-in-training with a flair for the dramatic, so you end up with passages like this one, in which she describes her grandfather Abraham practicing pole-vaulting as a teenager:

And here he is, Abraham in lift-off, his soul bubbling as he climbs, entering the upper air with perfect propulsion and ascension both. An instant and he no longer needs the pile. Hands it off. It falls to ground, a distant double-bounce off the solid world below. The blackbirds take fright, rise and glide to the goalmouth. Amazement blues my grandfather’s eyes. He’s at the apex of a triangle, a pale angular man-bird. His legs air-walk, his everything unearthed as he crosses the bar above us all. There is a giddy gulp of the Impossible and he sort of rolls over in the sky, pressed up against the iron clouds where God must be watching. His mind whites out. His body believes it is winged, has vaulted into some other way of being. Abraham Swain is Up There and Away, paddling the air above the ordinary and just for a moment praying: let me never fall to earth. (Pg. 8)

I for one love this kind of writing, but I know that it’s not for all tastes. So if you’re not so terribly fond of ornate prose, don’t say I didn’t warn you.

The River Shannon is also really important in this book. Here’s a shot of it from County Clare, where History of the Rain is set. (Although the weather for most of this story is not nearly this nice.) // Image by Liam Moloney, CC BY-SA 2.0

The River Shannon is also really important in this book. Here’s a shot of it from County Clare, where History of the Rain is set. (Although the weather for most of this story is not nearly this nice.) // Image by Liam Moloney, CC BY-SA 2.0

There are a few rough spots here and there. The symbolism, while very beautiful and poignant sometimes, could be a little heavy-handed at other times. And then there’s Ruth’s twin brother Aengus, known as Aeney to the family. Aeney gets talked about a lot in this story, but we never really get to see him do or say anything memorable. Really, most of what we know about him are the things that Ruth explicitly told us. We know that Aeney was kind because Ruth said he was kind, we know that he was the apple of his father’s eye because Ruth said he was the apple of his father’s eye. In other words, Aeney never really gets to speak or act on his own behalf. Personally, I would have appreciated if his character had been fleshed out a bit more.

Even so, my friend’s verdict still stands: this is a beautiful novel, full of the lyricism and wonder and the nerdy literature references that I love. Glad I could end Reading Ireland Month on a high note!

Advertisements Rate this:Share this:- More